Between Fire and Sleep: Essays On Modern Polish Poetry and Prose

Between Fire and Sleep: Essays On Modern Polish Poetry and Prose

Yale University Press, 2009

In the now canonical study Five Faces of Modernity (1977) Matei Calinescu suggested that the idea of modernity, born during the Christian Middle Ages, rests on the sense of unrepeatable time. Unlike in the world of pagan antiquity, where the sense of time was circular, modern time is a process of continuous change. In this temporal paradigm – our paradigm – at any given historic moment something begins and something ends, something is gained and something is lost (more often than not, irretrievably). Thus, the faster our reality advances, the more divided become our affects: the euphoria for new ideas and new possibilities (of which the future has a seemingly inexhaustible stock) is constantly checked by nostalgia for the times, people, and things left in the past. Nostalgia can be a dangerous sentiment, at the extreme leading to melancholy and resentment. Yet alternative ways of handling the past – especially one’s own – are never obvious. The question of how to incorporate the past into our present is always problematic. Can certain experiences or affects be successfully revisited or reconstructed? And if so – what is the point of doing so? What do we gain through such returns? Indeed, should we keep searching for the “lost time” (like Marcel Proust’s protagonist), or should we keep gardens of memory locked and focus on whatever lies ahead?

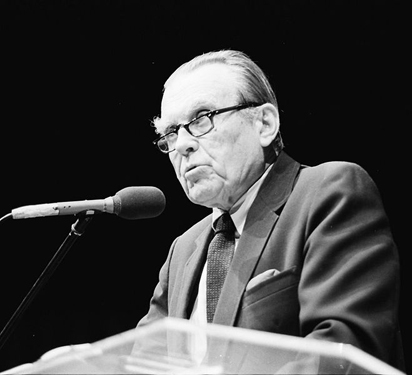

Czesław Miłosz at the Miami Bookfair International, 1986

via MDCarchives

These are but some of the questions one can entertain while reading Jarosław Anders’ Between Fire and Sleep: Essays on Modern Polish Poetry and Prose (2009); a book that by its author’s admission is at once a “farewell…to a certain way of reading, of living with literature,” “an attempt at a reconstruction of a certain mode of thinking about literature,” and “a kind of return” to Polish culture after “a long voyage” of emigration. The reason I started this essay with a pondering on our relationship to time and the past is that although Anders’ essays are ostensibly dedicated to literature – to some of the finest Polish authors the twentieth century has produced – it can also be read as a very personal record of a generational experience. For Anders’ generation – one that grew up in communist Poland – literature was more than mere entertainment or a pastime: it was “a constant companion and a stimulant that helped to overcome the universal inertia” (of communist Poland). It was, in other words, a very special form of engagement with (rather than escape from) the everyday reality; of bestowing it with meaning that could be at the same time more personal and more universal than the one offered by the official ideology of PRL (The Polish People’s Republic). Literature was thus not an “object,” but a collective experience.

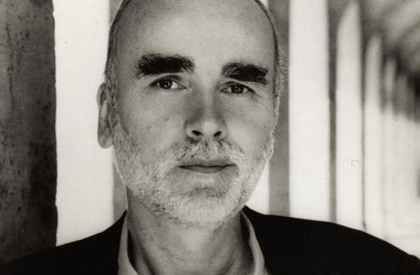

Wisława Szymborska

The questions we should ask are: How could this experience be shared? And what value would this particular interaction with literature have in our present moment? After all, the communist regime is no more. There is no more censorship; no intellectual oppression; no barriers between Poland and the West. Anders himself wonders “how few of [his] Polish literary friends, those living in Poland and those abroad, are still devoting most of their time and effort to literature. The vast majority of us are in politics, the media, even business. Some have retrained themselves as lawyers, political scientists, or economists.” In other words, in a free country literature does not need to function as a substitute for the myriad of unavailable life opportunities or intellectual fascinations. It can once again be simply “literature” and not “Literature.” So, to put the question boldly, why should we bother with the way it was read “back then”?

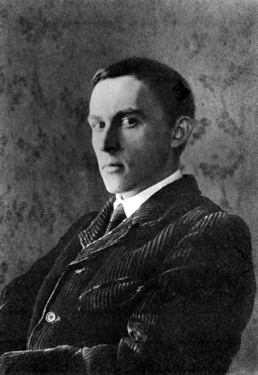

Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz aka Witkacy, ~1912

Here, I think, we should consider our present moment and our current ways of engaging with not just literature, but culture in general. Over the last few years our relationship with reality – especially through reading and writing – has changed considerably; more so than even Anders’ sense of temporal and spatial “displacement,” or his skepticism take into account. The time before super-fast Internet, social media, smart phones, and the ever-tightening network of global communication and finance seems far removed. We write differently. We read differently. We communicate differently. We process information differently. Thus, the problem is no longer the changing role of literature in the transition from communism to democracy. Rather, it is the changing role of literature in what we got used to call the Information Age. I want to make it absolutely clear: I am not joining the ranks of those who prophesy the doom of literature in mass-media-dominated culture. On the contrary: I believe we are witnessing the revival of reading and writing as a mode of communication. Furthermore, thanks to the internet and portals like YouTube, culture – in all its various forms – is more accessible than ever before. Yet we consume it and participate in it differently than we used to, there is no question about it. And it is in this context that we need to ask (again): can the way of reading literature that Anders and his peers experienced be of any value to contemporary readers?

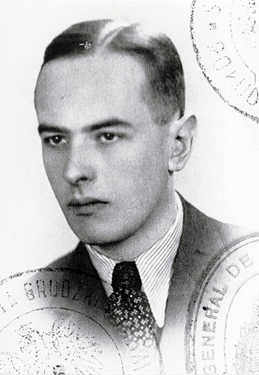

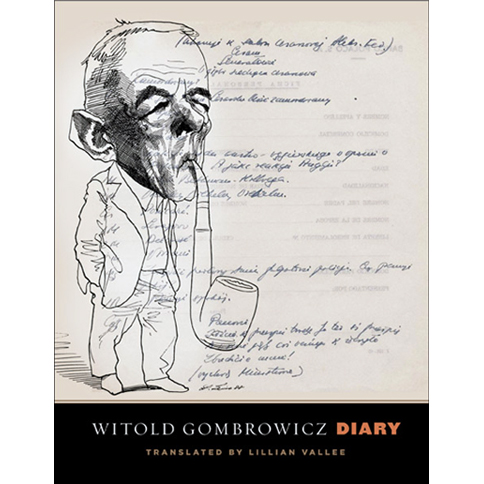

Witold Gombrowicz’s Polish government-issued passport, 1939

via the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library of Yale University

I think it does, although to answer it fully we need to look more closely at what Between Fire and Sleep has to offer. To begin with, let me say that despite its small size it is without doubt one of the best introductions to twentieth-century Polish literature. It does not have the vast scope of Milosz’s hitherto unmatched The History of Polish Literature (1969, 1983), but, as I already indicated, literary history is not what Anders is after. Also, whatever the book lacks as synthesis of Polish postwar literature it more than makes up for in other departments, which I will mention later. Between Fire includes nine essays based on reviews and essays previously published in The New Republic, The New York Review of Books, and The Los Angeles Times Book Review. Each essay focuses on a single Polish author. Anders considers the “three madmen” of Polish literary modernism – Bruno Schulz, Witold Gombrowicz, and Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz – followed by the grand trio of Polish postwar poets – Czesław Miłosz, Zbigniew Herbert, and Wisława Szymborska – as well as two significant figures of Polish postwar prose: Gustaw Herling-Grudziński and Tadeusz Konwicki. Closing the collection is the essay on Adam Zagajewski, who is, in the author’s own words, “both the last great representative of the Polish school and a bridge to the present, post-communist era in Polish literature.”

Bruno Schulz, ~1920-30

Although no taboos are being broken by Anders’ renditions of these figures and their work, the author does offer some interesting insights, as when he juxtaposes Bruno Schulz’s image of a recluse mythmaker with evidence of his social and professional canniness, or when he presents Konwicki’s grim satirical novels as a reflection on Polish collective consciousness, instilled with guilt by “the Polish ‘religion of freedom’.” This reminder about the essentially ambiguous stance of these authors towards the world and life is one of the most fascinating aspects of Anders’ collection; one often lacking in similar publications that are all too eager to pigeon-hole artistic personalities (Miłosz the Sage, Herbert the Moralist, etc.). No artistic path presents itself as superior; each is marked by doubt, uncertainty, anxiety, or a sense of the ultimate contingency of life. Anders shows literature – and one’s engagement with it – as a process of searching and (often enough) erring.

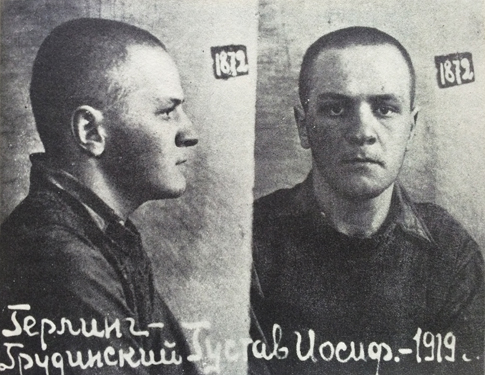

Gustaw Herling-Grudziński

NKVD prison photo; Grodno, 1940

“Myths are created in order to clarify the origins of things, the Polish poet tells us, and to insert meaning into the chaos of existence” he observes, [but] they may also be read as palimpsests with hidden meanings that have been rejected, concealed, as too dark or too disturbing to view in full light.” This is how Anders interprets Herbert’s stories, and further applies it to Herbert himself. It might as well be referred to the larger question of what literature does for us, even if we no longer put it on a cultural pedestal. Namely, it organizes and clarifies reality, but in doing so it also points to truths and experiences that escape our perception or comprehension. It points to possibilities fostered by imagination but also to our limitations as individuals and as collectives; to the numerous paradoxes of our existence. In communist Poland these were instrumental tools for breaking through the “mental wall” created by the state, but also for not allowing oneself to be caught up in the equally polarizing and often as dogmatic discourse of the underground culture (as satirized, for example, in Tadeusz Konwicki’s A Minor Apocalypse).

Tadeusz Konwicki

To return to the present situation and the question of the importance of literature today: there is obviously no single or unqualified answer and Anders’ goal is not to procure one; at least not directly. But its dual role of contesting and organizing reality around us certainly has not changed. As I mentioned, we are witnessing the return of the text (and storytelling) as universal forms of expression: there is the blogosphere, facebook, twitter, and multiple other internet outlets where nearly everyone today can express themselves in writing. Sharing content (and stories) in the form of text seems as natural as breathing for many of us. Most importantly, however, we continue to shape our understanding of reality in terms of narratives.

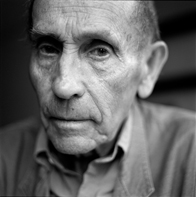

Adam Zagajewski

In fact, “story” seems to be one of the keywords of contemporary media discourse. “It is not about getting the story out first,” a commercial for a major news network proclaims, “but about getting the story right.” “So what’s the story here?” we ask when we want to understand a given situation. We even view our politics through this narrative prism. We do it more and more often, it seems, yet it becomes more and more difficult to orient ourselves among the stories that shape our existence. Simply put, we have lost the ability to read critically.

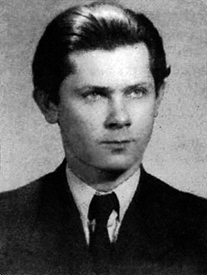

A young Zbigniew Herbert

The “old-school” engagement with literature becomes then an ideal polygon to sharpen one’s attunement not only to the “eternal questions” we keep asking ourselves with regard to our collective and individual existence, but also to the paradoxes and complexities of contemporary culture. Describing reality from multiple angles, finding unexpected correspondences, uncovering hidden meanings and hidden anxieties, facing contradictions and ambiguities, while inspiring wonder at the same time – all these important functions of writing and reading literature are as relevant today as they were half a century ago. Given our growing difficulties in representing the present moment – let alone sorting out all of the conflicting narratives and messages that keep bombarding us from everywhere – the ability to experience literature meaningfully – albeit in full awareness of its complexities and meandering meanings – is no doubt a worthy one to recover. Will it be possible? It is hard to say, although modern history has certainly witnessed more impossible comebacks. Perhaps the only way to find out is simply to try and Jarosław Anders’ Between Sleep and Fire is a great place to start.

CR

Pingback: Welcome to our Summer 2014 issue!