Rudolf Korwin Piotrowski

PHOTO courtesy of the Polish Museum of America in Chicago

Time and Place:

San Francisco, 1867-1878

Polish Exiles:

Rudolf Korwin Piotrowski: Customs inspector, Falstaffian inspiration for Henryk Sienkiewicz’s memorable character, Zagłoba

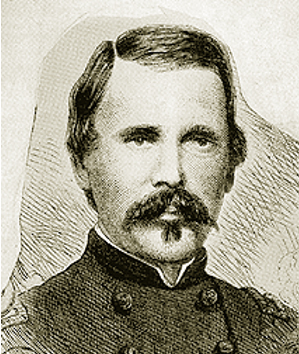

Włodzimierz Krzyżanowski: Civil War general, Treasury agent, tavern keeper

After Russia sells Alaska Territory to the United States, the government dispatches Customs Inspector Korwin Piotrowski to the Aleutians in 1867. The Treasury Department needs the big Pole’s fluency in the language of the Czarist enemies he fought as a youth. With projected government revenues in mind, he inspects the newly acquired “fur-seal fisheries” on the islands of St. Paul, St. George, and Unga. (He notes that Inuit hunters in one year kill more than 148,000 seals.)

Seal and salmon fisheries and general resources of Alaska. In four volumes. Volume I. July 24, 1897 Publication: Serial Set Vol. No.3576; Report: H.Doc. 92 vol.1

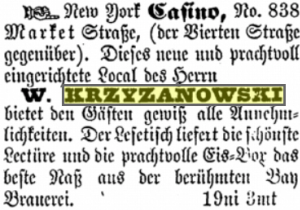

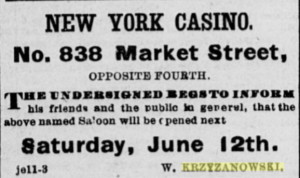

Nine summers have gone by since his return to San Francisco. But in 1876, shivering in the cool, grey city of fog, Korwin may wish for the fur-seal coat he could have bought in Sitka. It would have been a memorable sight, a tent with legs, as the corpulent expatriate walks into an uptown saloon at 838 Market Street. Oddly named, the New York Casino is a long way from Manhattan, and its few card tables are a few croupiers short of a gambling hall. Instead, the tavern has become a haven for Polish and German émigrés.

California Journal und Sonntags-gast. 19 September 1875, San Francisco

The proprietor is Włodzimierz (Wladimir) Krzyżanowski, known to everybody as General Kris, a Civil War hero who not so long ago commanded the Polish Legion and other regiments at the battle of Gettysburg. Now he commands two taverns, a few card games, and free lunch counters that dispute the ain’t-no-such-thing adage of a later century. He can exchange Alaska stories with Korwin. They play chess.

New to the saloon business, the General also leases an upscale lounge in the Financial District. At 236 Montgomery Street, it’s across the street from the Russ House. (A wooden three-story building in the Italianate style, the premiere hotel was built by heirs of Emanuel Russ, a silversmith and real estate investor. A German immigrant of Polish descent, he arrived a year before the discovery of gold.)

Daily Alta California, Volume 30, Number 10239, 23 April 1878

The bar is christened the Louver, a name that comes either from the celebrated museum in Paris (with an Anglicized spelling change) or, less probably, for a shutter with slats. Walnut chairs are upholstered in leather. Decorations include steel engravings and French chrome. The tavern is blue with the vapors of Havana cigars. Behind the walnut bar, a large French mirror looms above “elegant cut-glass ware” and trays of English cutlery. Thirsty bankers are tempted by the “choicest brands of foreign and domestic wines, liquors and cigars.

Helena Modjeska costumed for “As You Like It”

Major investors in The General’s saloons include a favorite customer, Korwin himself. No longer the state Commissioner of Immigration or a federal customs inspector, he has plenty of time to talk about Polishness with The General and, with him, to sample the choicest brands. His friendship with Krzyżanowski is further evidence of Korwin’s extraordinary gift for association with people who will become famous or important: Newton Booth, California governor and U.S. Senator; Governor Romualdo Pacheco; composer and pianist Fryderyk Chopin; poet and philosopher Adam Mickiewicz; author Józef Kraszewski; actress Helena Modjeska; her son, notable bridge engineer Ralph Modjeski; and author Henryk Sienkiewicz, whose adaptation of Korwin as a literary doppelgänger as yet unborn, is the warrior and libertine Jan Onufry Zagłoba.

At the New York Casino, Krzyżanowski makes a pitch for expatriates who, like him, fled the oppressions of the Old World and then survived somehow the minié balls and lethal dysentery of the Civil War. In the small workingman’s bar and restaurant, the air at noon is rich with whiffs of roasted garlic, fresh sauerkraut, and the sweet fumes from cherry wood in the kiełbasa oven.

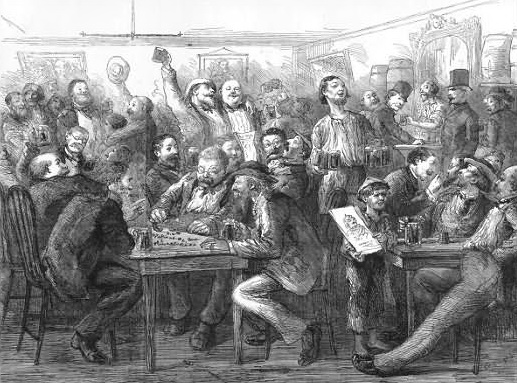

Korwin can converse with other Polish émigrés in their own beloved language. (It’s not Russian.) He can stand at the free lunch table, a fragrant institution in workingmen’s bars of San Francisco. “Any passerby may partake of this lunch,” writes a French traveler in 1859. After he samples a few, he adds, “Oyster soup, pork and beans, roast beef and potatoes, all the sacramental offerings, are spread out on a table, with a few pieces of thinly sliced bread. One grabs a plate and starts eating.” (“They had the most delicious dainties for the taking,” Jack London would reminisce about the saloons of his South-of-Market childhood, “strange breads and crackers, cheeses, sardines and sausages…”)

The only outlay is a slog or two of John Wieland’s Extra Pale Lager or any one of the drafts from intoxicating San Francisco’s eighty-plus breweries. Buying a 25-cent glass of beer or claret is encouraged but not required. (The language has yet to be enriched by “freeloader.”)

For Korwin, a typical plate might include smoked herring, stuffed cabbage rolls, and sourdough bread. And smoked herring, stuffed cabbage rolls, and sourdough bread. And smoked herring, stuffed cabbage rolls, and sourdough bread.

Colonel Kris

Gray eyes. Thick brown mustache. Slim. Confident. The handsomest general officer in the Union Army. His soldiers call him “Colonel Kris.” A first cousin of Chopin, he comes from Poznań (Posen) in the corner of Poland then ruled by Prussia. In 1846, the young university student joins a Polish armed conspiracy against Frederick William the IV’s autocratic rule and the incursion of land-hungry Germans seeping into his homeland, farm by farm.

“The hope for a better future which flashed before us like a meteor enchanted us, intoxicated us, and carried us away,” he would recall. “…I dreamed; I soared above the clouds; I went blindly where I was told, not reflecting over the consequences of such a rash pursuit of a vision.”

Betrayed by a fellow conspirator, the Greater Poland Uprising is snuffed before it begins. Fleeing the Prussians, Krzyżanowski emigrates to New York, learns English, becomes a civil engineer in Virginia, works on railroad construction, marries the niece of a noted general, makes a lot of money in her family’s pottery business, and supports with enthusiasm the election of Abraham Lincoln. On the second day after the attack on Fort Sumter, he says goodbye to pottery. He joins the Union army as a $13-per-month private soldier. He is promptly released from training to recruit volunteers in Washington, D.C., New York and Philadelphia. He organizes the New York Rifles. It merges with the Polish Legion. He blends immigrant Poles, Germans, Danes, Italians, Frenchmen, and Russians into the 58th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment, which he commands. A year later, he takes over as commander of the four regiments in the 2nd Brigade (including the 58th). It becomes “Krzyżankowski’s Brigade,” but he has yet to become a brigadier.

Edwin Forbes illustration of the Confederate attack on Cemetery Hill, July 2

PHOTO: GNMP Collection

The polyglot 58th fights in many of the uncivil war’s mutual massacres: Second Bull Run, Chancellorsville, Wauhatchie, and Cross Keys, among others. On the first day of the Battle of Gettysburg, Colonel Kris exhorts his brigade in a desperate defense of East Cemetery Hill (an appropriate name). The appalling casualty rate is fifty percent, which includes the killing or seriously wounding of all five of his regimental commanders. Krzyżanowski’s chest is crushed when his horse goes down, but he refuses to leave his troops. The next day would be worse.

James S. Pula, a professor of history at Purdue University North Central, tells the story in the Polish-American Journal:

On July 2, Krzyżanowski’s decimated force found itself in reserve near the Evergreen Cemetery near the spot where some four months later President Lincoln would deliver his famous Gettysburg Address. In the fading twilight of that evening, Confederate forces launched a surprise attack that broke through the Union lines, scaled the hill and took possession of the Northern artillery positions posted there. In those crucial few minutes, the fate of the Union truly lay in the balance.

As soon as the firing began, Krzyżanowski ordered his men into line, personally leading them in a counterattack aimed at the heart of the Confederate advance. Rushing into the gun emplacements, Krzyżanowski’s men fought hand-to-hand with the enemy, gradually reclaiming the artillery and forcing the Confederates back down the hill.

Southern historian Douglas Southall Freeman cited it as the closest the South came to victory at Gettysburg, but it was frustrated by the Polish colonel and his immigrant soldiers, preserving the Union victory and reversing the course of the war.

Many a history professor could cite other decisive events and turning points in the war that ended in defeat of the Confederacy, but few would disagree with the crucial importance of Krzyżanowski’s counterattack on East Cemetery Hill.

Edward Selig Salomon

Colonel Kris and Colonel Edward S. Salomon lead different units in the battle of Gettysburg and other actions by Germans, Poles, Scots, Italians, Jews, and the mix of every other ethnicity in the XI Corps. Its commander is a former revolutionary from Prussia, Major General Carl Schurz. Salomon, a German immigrant and Chicago alderman, commands the 82nd Illinois Infantry and is soon promoted to the brevet (interim) rank of brigadier general. Krzyżanowski’s single star is held up in the Senate for almost three years, a delay attributed to anti-immigrant prejudice by a few senators with roots in the Know Nothing movement. The promotion by President Lincoln is finally authorized by the Army.

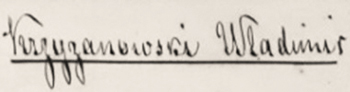

Włodzimierz Krzyżanowski’s signature

The snub is an unfunny joke, according to General Schurz. The colonel’s advancement had been stalled because legislators are said to be tongue-tied, haw haw, by pronunciation of the consonant-loaded “Włodzimierz Krzyżanowski.”

Could be true.

As Poles know, it’s not uncommon in America to see family names stripped of diacritical marks and, in too many cases, reassembled willy nilly. Many people in the public eye will say, somewhat disingenuously, “I don’t care what they write; just spell my name right.” For Rudolf Korwin Piotrowski, no such luck. It’s no big deal when Anglicization occasionally converts Rudolf into Rudolph and Korwin into Corwin or Corvine, but his family name produces a cornucopia of misspellings in the documents and newspapers of his adopted homeland. The list includes L’Otrawsky, Petrowski, Peatrowsky, Pidrowski, Penniski, Peadrowski, Piotrouski, Fiotrouski, Piotrwski, Pietrowiski, Pitrowski, Pitrowsky, Piotronski, Piotrowskie, Peotrowsk, Piotrowsky, Pettenski, Piobrowski, Liotrowsky, and, occasionally, his real birth name, Piotrowski. The most collectible: Rolfe Korwin Ratrowsk.

Korwin doesn’t help matters. Evidently assuming that “Piotrowski” is insufficiently Yankee, he sometimes adopts “Korwin” or “Corwin” as his surname. Confusion accelerates whenever he restores Piotrowski, drops “Rudolf,” and replaces it with “Korwin” as his given name. So be it.

After Appomattox, Krzyżanowski serves in various federal positions, including a stint as a Reconstruction administrator in what is left of Georgia after Sherman’s march. Joining the Treasury Department, he is sent to Washington Territory as a special agent. He goes to Sitka to gather information for the first detailed report on Alaska Territory. The assessment leads him to look into extensive customs corruption. (In Krzyżanowski’s memoirs in Polish, he mentions “my administration” referring to his successful investigation. According to biographer James Pula and Alaskan historians, “my administration” leads to mistaken assertions that he had been the territory’s first governor. He wasn’t.)

As he retires as the state’s Commissioner of Immigration, Korwin lives in cheap rooms in an unglorified alley. If financial trouble is the reason for his genteel poverty, he is not alone. On Black Friday in 1875, thousands of investors – including superbanker Bill Ralston himself – lose their shorts (and other tricks of the market) in the madness of stock speculations in the Comstock Lode. Ralston goes for a swim – and comes back under a sheet.

Saloon scene. From Every Saturday: An Illustrated Journal of Choice Reading. October 15, 1870

Friendship with Krzyżanowski will come at a price. He persuades Korwin to invest in the general’s tavern business with a loan of $1,000 ($23,000 in the currency of 2015).1 The biggest investor is General Salomon, who gives Krzyżanowski $2,500. Others include two stalwarts of the local Polish Society: Constantine L. Łuniewski, a customs inspector and sometime restaurant owner, $500, and his shipmate when they arrived in the USA, Captain Francis Theophilus Lessen, $150. They get stiffed.

Military success is no guarantee of business acumen or luck at the card tables. After three years in San Francisco (1875-1878), Krzyżanowski will eventually go broke, apologize to Korwin and other investors, declare bankruptcy, and move to Panama for another job with the Treasury Department. In the meantime, the New York Casino is cherished by San Francisco émigrés as an unofficial Polonia social hall. The vodka-flavored tavern resonates with disputations among exiles who, because they are outspoken patriots and nationalists, can never go back to occupied Poland. This does not mean that on many an important issue they can’t disagree. It’s a Polish tradition.

Consider Korwin’s own circle. His close friend, mapmaker Kazimierz Bielawski, a personable man with gray whiskers, looks like Confederate general Robert E. Lee. The resemblance is only beard deep. A socialist freethinker, he quotes Voltaire. He argues often with Dr. Ladislaus Pawlicki. The naval surgeon deserts his Russian warship in San Francisco when Polish rebels are fighting Russian armies in the January Uprising of 1863-1864. Described by Helena Modjeska as “a staunch patriot” and “an ardent and practical Catholic,” Pawlicki disagrees in turn with Korwin. The big man is burdened with “aristocratic leanings and prejudices,” says Modjeska. (All three men are involved in supporting the Polish actress in a crucial year when, broke and daunted, she begins at midlife the American career that will place her among the greatest Shakespearean performers of the century.)

Polish aristocracy comes into play whenever exiles wrangle about the meaning of polskość, or Polishness. It is usually defined as “the cultures and identification of Polish people,” but this seemingly simple description opens a forest of conflicting interpretations rooted in the complexities of class, region, birth, politics, and individual perversity.

If Modjeska is consulted, she would add sadly that Poles belong “to the vanquished of modern history.” In The Arena, a short-lived journal published years later in Boston, she says, “We do not possess that superb confidence in our own forces, which is the beginning of success. We do not believe with sufficient energy in our lucky star, in the superiority of our own country above all others, in the complicity of the God of armies in our battles. With us patriotism is not aggressive, and it is not circumscribed by certain well-fixed geographical limits.”

Daily Alta California 11 June 1875

The General doesn’t crowd anybody’s memory with what he says, if anything, about the barroom debates. He may be a living icon of Polishness, especially to Korwin, but his silence makes sense. Any prudent publican will store his opinions under the cash box.

In an article for a Polish magazine, Krzyżanowski praises Americans (“bright, intelligent, loves comfort, is hospitable, and very practical”). He adds: “How often jealousy arose within me as I watched those who were surrounded by landscapes of their native land, rock to their native songs, satiated with the clear tones of their native language. These people were able to prolong their youth by living in familiar surroundings. However, not all of us can do this…”

In a letter to his niece back in Poland, he adds, “To me the most modest home in my native land would look better than the greatest palace here. In the former burns the heart of the family, in the latter just the emptiness.”

One contemporary thinker argues that Polishness involves “the metaphysics of the Polish soul.” To another, Polishness is defined less philosophically. He says it begins with smoked cheese, kiełbasa, and pickled herring in sour cream.

Korwin never passes up a plate of pickled herring.

When he tires of polemical gambits, he can ask The General for a game of chess.

Kibitzers know that this is perhaps a poor time to argue about Polishness with the big Polander. They remember the day when Korwin affirms a rhetorical point with a casual slap on the chess table.

It collapses.

CR

Acknowledgement: James S. Pula, Ph.D.; professor, Purdue University North Central (Westville, Indiana); past president, Polish American Historical Association. See: Pula, James S. For Liberty and Justice: A Biography of Brigadier General Wlodzimierz B. Krzyzanowski, 1824-1887. New York: Syracuse University Press, July, 2009.

Pingback: Welcome to Summer 2015!

Fascinating. I totally believe the lack of advancement for Krzyżanowski based on an inability to pronounce a Polish name. Mine is three simple syllables and people still mangle it.

Do the current owners and/or businesses at 838 Market know its history?

Lynn and Maureen – You guys have done a fantastic job! This really evokes old San Francisco. It is funny, informative, and lively. I can almost taste the kielbasa on the free lunch. -Pauline

GREAT STORY

I read the story about Krzyżanowski and Piotrowski from begining to the end. Very interesting.

Pingback: 1905, A Very Good Year