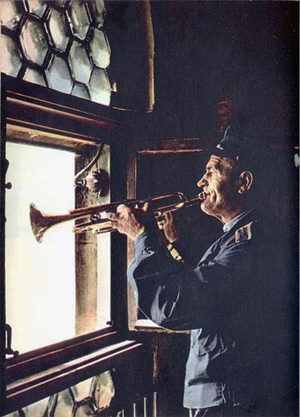

PHOTO from 1968 “Streets of Kraków” guide: Hejnał player.

It’s an exciting idea: becoming a witness to history. But when that happens to us, it may be in a way that’s unexpected or even unwelcome, as when people find themselves victims of war or terrorism. I became a witness to history in a way that started out unassumingly enough. In 1988 I was working for a newspaper that had a travel column and a daredevil editor who wanted her reporters to visit Third World or communist countries.

As my colleagues and I were mulling over destinations, I saw Leslie Stahl speaking from Kraków on the CBS Evening News. With the Mariacki Church behind her, she pointed out that the hejnał, the trumpet call from the church’s tower, had been played for six hundred years. Stubborn people, I thought. I like that. I knew that Poland had produced Chopin and Paderewski and Madame Skłodowska Curie, and that one of its primates, Cardinal Wyszyński, had been imprisoned by the communists. I decided to go to Poland and meet those history-loving diehards who in communist times still played the old trumpet call from Mariacki.

But how to get into a country whose regime was hostile to the United States? No problem there; the Polish government, hoping to build up the tourist industry, was running study tours for American writers and it was easy to get on one. I was nervous when, a few weeks before my scheduled departure on October 1, some acquaintances of mine who had gone to meet with other peace activists in Czechoslovakia had been expelled from that country for attending a meeting the authorities declared illegal. But in my editor’s view, if that happened to me, it would be a better story than a conventional travel piece. So I found myself at Kennedy Airport boarding a Russian plane—Lot, the Polish airline, was using IL62s then—for an astonishingly smooth overnight flight to Warsaw.

1974 PHOTO of LOT Polish Airlines’ Ilyushin Il-62 at Okęcie Airport

On the plane an attractive young stewardess proved so friendly that I ventured to ask her if she thought Solidarity, which had the support of a quarter of the Polish population, would get the concessions it was seeking from the government. “I think we will win,” she said with a confident smile. “It is our soul.”

Neither I nor the seven other writers in my group knew it, but her remark—and the fact that she was not afraid to make it—was the first of many signs we would see that the Warsaw Pact, one of the major sociopolitical monoliths of the twentieth century, was falling apart. I got another clue when we landed unexpectedly at Gdańsk at six o’clock the next morning to wait until a fog from the Vistula in Warsaw cleared up. We stepped off the IL 62 and walked in a freezing Baltic wind to the terminal, a small building with the spare, improvised look of a temporary military airport.

If Russia’s major client state had infrastructure no better than this, I thought, the Cold War was not what I’d been led to believe. And was it possible that people with so few resources could assert themselves against the Moscow-based communist regime? How? With moral resources? What were moral resources without money? Wait! As an American, I was supposed to believe that moral resources could win wars. Already Poland was telling me something about myself.

The fog lifted and we reached Warsaw, where my fear that we would have to sit through interminable dinners capped off with praise for the Party’s achievements was instantly dispelled. Our senior guide unveiled a program emphasizing historic and religious sites and places connected with Solidarity. Not from him, for he had to maintain decorum, but from other sources, we were treated to samples of Polish humor. Why do the police go around in twos? Because one of them can read and the other one can write. The best joke of the period that I heard went like this: In a long line in front of a shop, a lady begins to weep about the shortages of goods. A policeman says, “Now, now, madam, others are worse off. Why, in the Sahara they don’t even have water.” “No water?” the woman almost screams. “How long have the communists been in charge there?”

We saw shortages, too. We were taken to one store that had a pile of tires, several boxes of chocolates, a heap of T-shirts with graphics that showed their foreign origins, and other oddly assorted merchandise, much of it simply piled on the floor. A children’s shop displayed clothes and blankets that were unbelievably drab and flimsy, like the clothes and shoes many people were wearing on the street. What we saw confirmed what we had heard about the plight of consumers in communist countries, though the distribution system had not always performed as poorly as it did that Fall.

PHOTO of Oliwa Cathedral Grand Organ by Diego Delso

From Warsaw we were flown to Gdańsk, a destination the magazine writers in our group were eager to reach because Solidarity was so much in the news. As our minivan passed the Party headquarters, our local guide, a bluff, hearty elderly man who had decided he was through with the communists whether or not they were through with him, laughed out loud as he told us how the building had recently been set on fire, forcing the committee members to escape by helicopter from the roof.

The next day our senior guide wanted to take us to a concert on the eighteenth-century organ with more than 6,000 pipes at the archcathedral in Oliwa. Our magazine writers, lugging pounds of camera equipment with them, were impatient because they wanted to photograph sites in Gdańsk connected with Lech Wałęsa, but their respect for the guide’s expertise and strength of personality muted their dissent as we made our way to Oliwa shortly before one p.m. The church was packed but quiet, with a very reverent atmosphere. The side altars were loaded with necklaces, offerings from women who believed they had had prayers answered. If the Russians tried to get Poles out of their churches, I thought, they would have a blood bath on their hands.

The irrepressible local guide took me and another woman from our group up on the platform to view the tall, elaborately carved Baroque altar. Below the steps leading to the platform stood an old verger wearing knee breeches, stockings and a blue velvet coat. He had the aristocratic nose to go with these clothes, and an appropriate sober expression. Even a Briton might have seemed a bit self-conscious in this outfit, but the elderly Pole looked as though he had been born in it.

We didn’t touch the altar, of course, but we stood within a few inches of it. Then we filed down past the verger, who nodded gravely to the other woman and me, then stopped our guide and scolded him quietly in Polish. I suspected, and later confirmed, that the old man was reprimanding the guide for taking us too close to the altar. It was not just a costume, this blue velvet jacket; this man was not just there to enhance photo ops. He was defending the atmosphere of God’s house.

That was indescribably moving to me. I had been at Canterbury Cathedral with my family, and unless a service was in progress, Canterbury was simply an historic site, with people talking at full voice and no atmosphere of devotion. I thought all European Christian nations had evolved into secular societies sheltering a small minority of individuals of faith. But here, it seemed, not only was communism fraying at the seams; some strength in Polish people had also survived secularism and depersonalization. I had thought of East Europe as a breeding ground for existential pessimism and mechanistic, reductive views of human beings. Not only was I not finding that here, but being here was helping me heal from those ways of thinking.

PHOTO of St. Mary’s Church in Kraków by Pgkos

Our next destination was Kraków. Wawel, a child’s dream of an ancient Continental castle, won my heart after a stunning tour by our guide and two expert historians. Its mammoth bell, Zygmunt, was made of metal from cannons used in battles Poles had won through the centuries. “Forged from the cannons of our victories”; so this was a nation of poets. The bell, the hejnał, and, on the streets of Warsaw, the fresh flowers under the plaques to people randomly shot by the Nazis, were evidence that memory was a very strong functioning organ in this society. And the people our group had met seemed much more committed to being Poles than to being communists. I wondered if that was part of the reason Stalin once said that trying to impose communism on Poland was like trying to put a saddle on a cow.

The air in Kraków in those days was so toxic that a jogger in our group was warned not to run at full speed. The honesty of our guides about that was surprising to me, and even more surprising was the remark of our senior guide about the foul emissions from the Nowa Huta industrial complex near the city: “You don’t need a war to kill you. You can die of pollution.” As a reporter, I had come up against refusals on the parts of officials in the United States to be frank about pollution and its dangers; for a government-licensed guide in a country with a chill on free speech to be so openly truthful about it seemed remarkable. It was actually another sign that the system was close to collapse, as was the wry complaint from staff in our hotel that “some people,” meaning apparatchiks, were allowed to drive cars in the medieval city core, while ordinary people were not.

PHOTO of Nowa Huta steel mill blast furnace by Zygmunt Put

Later I was told that one of the major reasons for Poles’ disaffection with the regime was environmental deterioration—that even people with no interest in politics were outraged when they saw their children’s skin covered in rashes from toxins leaking from industrial plants near large apartment blocks.

Back in Warsaw for the last evening of our tour, we drove to the Wielki Theatre for a Penderecki concert. We passed through the middle of the city while it was still light and found ourselves in the midst of a demonstration: hundreds of people facing perhaps a dozen police. No one moved, no one shouted or threw things, but the looks on the demonstrators’ faces were unnerving. I remembered footage of race riots and demonstrations against the Viet Nam war at home. I remembered angry faces, obscenities, shouting, fighting, police clubbing activists. You are our government and we are outraged with you, the American faces said. But the quiet, cold Polish faces said something with an implacable finality: We do not acknowledge you as our government. We do not know you. Rage and shouting are past; we are utterly estranged.

As our minivan hurried on to the Wielki, we wondered what the future would hold for Poland. On a more cheerful note, we had heard at one of many press conferences the voice of a young employee of Orbis, the national travel agency, who had his own way of sizing up the future, or at least the future of tourism in Poland. Older Orbis officials, said this hopeful newbie, “think sightseeing means going to the churches. I try to tell them there is more money in fly fishing.” Was there a chance that the government would legalize Solidarity, we asked him. “They will have to find some way to do it,” he said. “Solidarity is ten million of us.”

Back in the States after the tour, I faced a dilemma about how to conclude my article about Poland. We eight writers, hearing such optimistic predictions from Poles, wished them good luck; we did not tell them that we thought the odds were against them. For us, optimism meant hoping the Russians would not retaliate against Solidarity with an armed attack. I ended my story by quoting the cheerful prediction of the fly fishing advocate and declining to hazard one of my own.

The next year it became clear that what we had heard in Poland had not just been wishful thinking. The Round Table talks took place; the government legalized Solidarity; the one-party system collapsed, and for the communists it was game over.

There was one more surprise for me. It became apparent late in 1989, when the Berlin Wall fell, that our intelligence services had been astoundingly unprepared for the changes in East Europe. Was it possible that a group of fairly average reporters, photographers and food writers had heard things the CIA hadn’t heard? That skilled operatives hadn’t known what cab drivers in Warsaw were talking about openly the previous fall—that the regime was in its last months?

I telephoned the office of then-Senator John Kerry, whose staff always took press calls. Yes, it was possible, said Kerry’s foreign affairs analyst, because the intelligence services relied on electronic listening devices instead of talking to people and gathering what was known in the trade as “humint,” or human intelligence.

This was the last piece of information I needed to understand that as a way of seeing my country and the rest of the world, the Cold War paradigm was obsolete. Of course, there were business interests in my country who did not want to see that paradigm break down. Communism and capitalism—these are just names, someone in Poland had said; the real game is power. The communists had failed to keep their empire together, but my government had failed to understand what was really going on inside that empire, though understanding it had been touted as our major intelligence goal since the end of World War II.

What would happen to that brave, eloquent country now? I had no Polish background whatsoever, no grandmother, no Polish relatives as far back as my family’s history has been traced. I had gone to Poland almost on the flip of a coin. But somehow I had found a root there, and I had to go back. I had to be a witness to whatever happened next.

CR

***

Stephanie did return to Poland in 1990, and that year she began to study Polish, which eventually made Polish literature accessible to her. She has visited Poland every year since then. She saw the country march with dignity—without the retaliatory purges long seen in Russia after changes of leadership—into a free future. There were no catastrophic lurches in the economy. Though most of them had been brought up outside a free market system, Polish people showed such pent-up talent for business, and Poland was sufficiently attractive to foreign investment, that within five years after the first free elections, the cities had attractive shopping districts and an unbelievably improved standard of living.

Stephanie was privileged to observe the election in which Poles voted overwhelmingly to join the European Union, and the celebration in Warsaw’s Piłsudski Park the night Poland became a member. Though a shortage of capital and jobs still forces many young Poles to look for work in Britain and elsewhere, Poland is stable and productive and in 2014 celebrated twenty-five years of freedom.

Pingback: Welcome to Fall 2015!

Thank you for your story. It was beautifully written. I went to KUL inLublIn in 1992. It was a wonderful experience visiting my Parents’ birth place. I remember the awe when going to all the church r s & cathedrals. The one in Oliva was so amazingly detailed and carved.

Hi Stephanie,

It’s been a great many years since I last saw you and David. I’m still here in Rochester, though I’m now an owner of an art gallery, since my retirement from Xerox on 2005. I still have fond memories of our time at the U. Of R. and of my abortive attempts to play golf with David.

Hope you are well. (I didn’t know you spoke/read Polish, or was this a later acquisition?)

My regards to Dave.

Jim Hall