Diary

Diary

By Witold Gombrowicz

Translated by Lillian Vallee

Yale University Press

2012

Witold Gombrowicz was well known for his polemical and unforgiving attitude towards his critics and commentators. He firmly believed that an intellectual should never shy away from argument, particularly concerning him- or herself: not even if the opponent proves to be inept. A considerable portion of Diary is dedicated to such a back and forth between Gombrowicz and those brave or careless enough to challenge him, both in communist Poland and amid the émigré circles.

I cannot therefore approach the task of reviewing his most personal and, arguably, most accomplished work without feeling somewhat insecure; all the more so given the enormous body of scholarship on this extraordinary work that has accumulated over the last few decades. After all, as Jan Bloński remarks, Diary is the crown and the key to everything that [Gombrowicz] wrote; an introduction to his art, which is hard to fully comprehend without such auto-commentary, and one of the most puzzling of his creations that itself cannot be fully comprehended.”

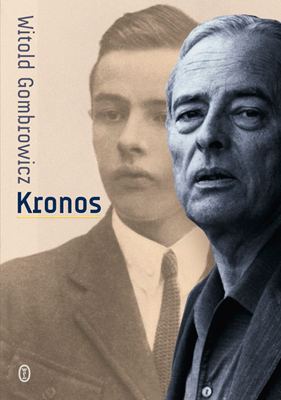

Then again, timidity would never be an approach Gombrowicz himself would endorse, so hopefully my humble attempts will not stir his ghost from the grave (let alone his living ardent readers). Last year’s publication of Kronos – advertised by the publisher and the media as Gombrowicz’s “intimate” diary – and the discussions this book has initiated offer an excellent opportunity to revisit what might be termed the author’s “public” diary. For that, the recent re-edition of Lillian Vallee’s translation, out of print for a long time, could not have been timelier.

Then again, timidity would never be an approach Gombrowicz himself would endorse, so hopefully my humble attempts will not stir his ghost from the grave (let alone his living ardent readers). Last year’s publication of Kronos – advertised by the publisher and the media as Gombrowicz’s “intimate” diary – and the discussions this book has initiated offer an excellent opportunity to revisit what might be termed the author’s “public” diary. For that, the recent re-edition of Lillian Vallee’s translation, out of print for a long time, could not have been timelier.

The first pages of this unique text were written in 1953, at the time when the most difficult period of Gombrowicz’s life – a time of poverty and obscurity as an émigré in Argentina, where he arrived on the brink of WWII – was coming to an end. Thanks to the help of his friends, he managed to translate his major novel Ferdydurke and by the time he pitched the idea for Diary to Jerzy Giedroyc, Kultura’s chief editor, he had managed to secure a modest sustenance and a moderate reputation for himself. Consecutive sections of Diary were published in Kultura from 1953 to 1969 (he died in 1969 of respiratory failure).

The first pages of this unique text were written in 1953, at the time when the most difficult period of Gombrowicz’s life – a time of poverty and obscurity as an émigré in Argentina, where he arrived on the brink of WWII – was coming to an end. Thanks to the help of his friends, he managed to translate his major novel Ferdydurke and by the time he pitched the idea for Diary to Jerzy Giedroyc, Kultura’s chief editor, he had managed to secure a modest sustenance and a moderate reputation for himself. Consecutive sections of Diary were published in Kultura from 1953 to 1969 (he died in 1969 of respiratory failure).

The concept of the writer’s diary is part of a long tradition that includes, among others, Dostoevsky’s Writer’s Diaries and Andre Gide’s Journal (the latter gave Gombrowicz the idea for his Diary). It is a heterogeneous genre that serves as the author’s platform from which he or she can comment on new developments in literature, art, philosophy, politics, as well as reflect on more private issues. What we find in the Diary are Gombrowicz’s famous polemical essays on Polish national character (which have not aged a bit since the time they were written), pre- and post-war Polish literature, and the role of art in society; also, reflections on Catholicism, existentialism, and Marxism; accounts of the author’s life in Argentina, dealings with editors and critics, and – perhaps most importantly – studious self-analyses.

Some of these writings belong to the historical moment in which they were published and as such form an interesting personal account of the postwar intellectual and cultural developments. Some of them, however, are shockingly current and could easily illuminate contemporary cultural debates. This rich assortment of subjects is matched by the generic variety of the diary: we find here, among others, reminiscences, reviews, polemics, philosophical essays, feuilletons, and travelogues; entries written in the first and third person.

Despite all this diversity, however, the authorial persona is a powerful unifying factor and at no point does the reader get any sense of incoherence or chaos. So much so that even the seemingly pointless entries acquire meaning in the context of the rest of the text. The author’s conversational and direct style never allows the readers to get lost in a sea of abstraction. Especially that his dual strategy of teasing the high-minded with ludic buffoonery and the pretentious ones with a mixture of irony and elitism is not only rhetorically efficient but makes for a thoroughly entertaining reading. At this point it is also worth mentioning that Vallee’s translation comes as close to capturing the spirit of the original as one could hope.

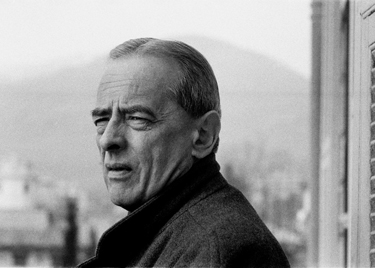

Witold Gombrowicz in Vence, France; 1965.

Photo: Bohdan Paczowski via Culture.pl

There are a few things one must keep in mind when approaching this highly untypical work. First of all, one of the defining characteristics of the diary as an autobiographical genre is that unlike memoirs, it is written in fairly regular intervals within a given time frame (in the case of the majority of literary diaries, usually spanning several years). What it means is that they are not products of a personality anchored at a particular point in time, but rather reflect their creator’s evolution. In line with this aspect of the genre, Diary is a record of becoming rather than being. In fact there is nothing that scares the author so much as the gradual and invisible process of ossification of one’s personality. As the author writes at the end of the first volume, somewhat distraught: “This awareness: that I have already become myself. I already am. Witold Gombrowicz, these two words, which I carried on myself are now accomplished. I am. I am too much. And even though I could still do something unpredictable for myself, I no longer want to.”

Diary could be read as Gombrowicz’s attempt to escape the finality of becoming oneself once and for all. It is, as it were, a window into Gombrowicz’s inner transformation and at the same time a means of enabling this transformation: a flexible and fluid literary form (the diary) that reflects and stimulates the flexibility and fluidity of the mind behind it; an elixir of youth of sorts.

The second thing to be wary of is the authorial design behind this work. Its oft-quoted first few entries read:

Monday

Me.

Tuesday

Me.

Wednesday

Me.

Thursday

Me.

What this playfully narcissistic opening emblematizes is not only the author’s egotism (quite honestly disclosed on several occasions throughout the diary) and ironic attitude to literary conventions (and others as well), but also – and perhaps most importantly – the artifice of the whole enterprise: the fact that Diary from the start is conceived as an artistic project rather than a genuine inside look at its author’s life and workshop. It is Gombrowicz experimenting with his self-presentation rather than Gombrowicz revealing himself: “by taking you to the backstage of my being, I force myself to retreat to an even more remote depth.” And perhaps this is the more interesting way of recording one’s development: comparing this work with Kronos only demonstrates how dull a reading of a truly documentary account of one’s life can be. Unlike Kronos, Diary does not need to be adorned with colorful illustrations and promoted with an aura of scandal. It stands entirely on its own as an original work of art and a fascinating tale about a particular period in the cultural and intellectual history spun by an extraordinary (if self-admittedly untrustworthy) narrator.

Witold Gombrowicz in Vence, France, 1965.

Photo: Bohdan Paczowski via Culture.pl

Gombrowicz wrote this work as a way of communicating with his readers, but also as a way of manipulating them. “I would like people to see in me that which I suggest to them. I would like to impose myself on people as a personality in order to be its subject forever after that. Other diaries should be to this one what the words “I am like this” are to “I want to be like this.” Gombrowicz’s philosophy of inter-human relationships was that of constant psychomachia: like the protagonist of his programmatic novel Ferdydurke, the individual human being is constantly torn as he tries to express him or herself in a unique and authentic way, yet cannot but be influenced by the Form, a sum-total of conscious and unconscious ways people manipulate, influence and affect one another: not only through ideologies and social norms, but even more fundamentally by their sheer presence to one another: by attitudes, micro-gestures, by the unspoken savoir-vivre. In Gombrowicz’s own words:

“I do not deny that the individual is dependent on his milieu – but for me it is far more important, artistically far more creative, psychologically far more profound, and philosophically far more disturbing that man is also created by another individual man, by another person. In chance encounters. Every minute of the day. By virtue of the fact that I am always “for another,” counting on someone else’s seeing me, being able to exist in a specific manner only for someone else and by someone else, and existing – as a form – only through another.”

(Truly, a ride with a stranger on an elevator becomes quite an experience after a lesson of Gombrowicz’s psychology.) So how can we act to assert our autonomy as individuals? The only way to defend oneself against the “Form” is to consciously play the game, to take the process of self-creation into one’s own hands. This was the initial motivation behind writing and publishing Diary. As the author presented his idea to Giedroyc, “I have to create Gombrowicz the thinker, Gombrowicz the genius, Gombrowicz the cultural demonologist, and many other necessary Gombrowiczes.”

Yet one should always be cautious what one wishes for. What happens once Gombrowicz transforms from a rebel and outcast, an infant terrible of Polish literature, into a world-renown artist and even a modernist “classic”? It turns out that he no longer needs to fight for the recognition of his talent and originality, and must begin to defend himself against the forces that carve a fixed place for him in intellectual history: against classifications, misreadings, and misrepresentations. The successful strategy now turns against the strategist: in the plurality of masks – be they social, cultural, or intellectual – where does one find the authentic self? Which Gombrowicz is the real one? And how to protect him against the other, “false” ones? This tectonic shift in the artist’s life is one of the greater narrative arcs of Diary: one that, as Gombrowicz himself admits, he failed to fully flesh out. However, the failure of the artist is not necessarily the failure of the work of art itself.

Overall, Diary offers a truly uncanny reading experience, one that is guaranteed to stay with the reader for quite a while after finishing the book. Although the reader never truly forgets that the author is playing a chess game with him, the game nonetheless creates a sense of intimacy. It may reveal itself in unexpected ways. On my first reading, when I still felt the reassuring thickness between my thumb and the back cover, I suddenly stumbled upon the editorial afterward instead of the expected next entry. I suddenly realized the significance of it: I just read the final entry. This is it. I reached the end of Diary and, by implication, also the end of the author’s life. Thus, through this work, Gombrowicz’s death caught me entirely by surprise. I finished somewhat shocked and distraught. At this moment I sadly realized I really enjoyed the game and I even came to like my partner, regardless of whether he was real or just one of his own artistic projections. And I look forward to another round.

CR

Pingback: Welcome to our Summer 2014 issue!

Pingback: Welcome to Winter 2016!