A now-closed San Francisco laundromat

Don’t CALL it Frisco. Whenever Korwin Piotrowski contemplates a trip from the diggings, he says he is going to Frisco. Nobody corrects him. From the Gold Country to the Golden Gate, San Francisco’s alternate name in the 1850s is uncontroversial among miners, prospectors, farmers, gamblers, and sailors – especially sailors.

The taboo comes later.

“Frisco” springs from an old Icelandic-to-Middle English term for safe harbor. According to the late Peter Tamony, [Peter Tamony. “Sailors Called It ‘Frisco.’” Western Folklore. University of California Press: July 1967, pp. 192-195] the Mission District’s respected slang detective, “Frith-soken” meant “refuge” or “sanctuary.” Because San Francisco Bay is just such a haven, sailors called it Frisco Bay. When the boring pueblo of Yerba Buena was renamed San Francisco, the boomtown by the Bay soon became Frisco – and frisky. In a few short years the antique word morphed into a jolly synonym for the non-Victorian pleasures of the Barbary Coast.

As if banning a name might somehow restore virtue to Terrific Street (the salt-water term for bawdy Pacific Street), the F-word is soon denigrated as low-class slang. It vanishes from the parlors of the newly minted nabobs of Rincon Hill, the cotillions of their hoop-skirted daughters, and the salons of their bejeweled wives. (Before their husbands struck it rich, many a matronly language snob had been a boarding house widow or a laundress with ambition.)

As if banning a name might somehow restore virtue to Terrific Street (the salt-water term for bawdy Pacific Street), the F-word is soon denigrated as low-class slang. It vanishes from the parlors of the newly minted nabobs of Rincon Hill, the cotillions of their hoop-skirted daughters, and the salons of their bejeweled wives. (Before their husbands struck it rich, many a matronly language snob had been a boarding house widow or a laundress with ambition.)

They prevail. More than a century later, (censored) is an unmentionable epithet in its home town.

The prohibition would have surprised Korwin in the era of sail. A frisco was then a sheltered inlet. In a safe place where sailors scrape encrusted barnacles from the hull, a wooden ship could be repaired, repainted, and revamped. Old maps show a Frisco River on the Ivory Coast of west Africa and a long-forgotten port of Frisco in North Carolina. (The booming Texas city of Frisco was born as a whistlestop on the old St. Louis-San Francisco Railroad.)

The city’s lingo police, oblivious to the annals of slang, mistakenly condemn Frisco as a verbal sin or, in the jargon of etymology, a syncope. That scholarly term applies to ugly clippings, or contractions, such as Sacto, San Berdoo, Narlins, Looville, or (yuk) San Fran. It doesn’t apply to Frisco.

Anti-Frisco activists have been heard to assert that the persecuted little word is the diminutive of Francisco. If that were the case, Herb Caen would have told his readers, “Don’t call it Pancho.”

Pink Floyd apparently did not get the memo

The war on Frisco didn’t start with Caen, but the newspaper columnist engraved the taboo on the citizenry’s mindset with the title of his book in 1953, Don’t Call It Frisco. He later changed his mind, but it was too late. No teacher, politician, or newscaster since then has ever been heard to say “F—-o,” at least not in public. If an unwitting tourist should blurt the word, she is more to be pitied than censored.

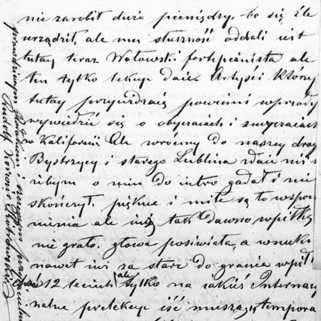

That was now; this is then: On one of Korwin’s letters, he writes his return address as “San Frisco.”

Let’s not go there.

CR

No mention of Emperor Norton?

Thanks for mentioning Emperor Norton. We are well aware of him, but his story is a sidebar to the history of the term “Frisco.”