Good Blood, Bad Blood: Science, Nature, and the Myth of the Kallikaks

Good Blood, Bad Blood: Science, Nature, and the Myth of the Kallikaks

By J. David Smith and Michael L. Wehmeyer

American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 2012

In another review in this issue of CR, Stephen Drapaka discusses the fervent work of academics, newspaper editors, journalists and authors who enthusiastically supported the pseudoscience that promoted their notions of a German master race.

In Good Blood, Bad Blood: Science, Nature and the Myth of the Kallikaks, a new book published by the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, authors J. David Smith and Michael L. Wehmeyer examine another study of the eugenics mania, this one by the psychologist and eugenicist Henry Herbert Goddard. His desire to engineer a better human had the support of intellectuals who firmly believed in their science and used it to promote their ideas of society.

Toward the end of America’s Gilded Age, the Industrial Revolution turned its focus to technology. America no longer wanted to simply manufacture products, but rather engineer superior products through science. As inventors like Thomas Edison, Nikola Tesla and Alexander Graham Bell ushered in a new era in industry, scientists like Charles Darwin and his cousin Francis Galton were connected to breakthroughs in human development. And it was during this Progressive Era that Galton misapplied his cousin’s theory of evolution to create Eugenics (Greek: ευ ‘well’ + γονική ‘born’) in which he believed “undesirable” traits could be bred out of the human species.

Industrialists like cereal tycoon Dr. John Harvey Kellogg jumped on the cause, in 1906 creating the Battle Creek (Michigan) Sanitarium and Race Betterment Foundation. Better breeding through science would advance humanity in a similar way that electricity would usher in scientific breakthroughs in industry.

Studying the “racial hygiene” of families was an exciting field made popular in 1877 by American sociologist Richard Dugdale’s study of families with frequent criminal records. But, although he recommended public health and early education rather than eugenics, the public preferred the interpretation that heredity is responsible for morality, enabling eugenicists to illustrate just how much money these ‘degenerate’ families cost taxpayers.

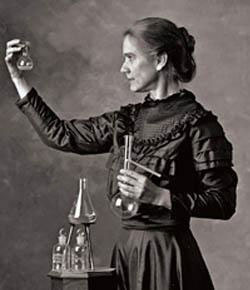

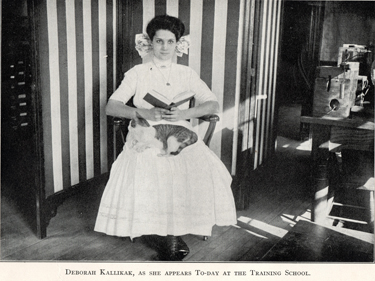

In a photo in Goddard’s book, “Deborah Kallikak” is shown sitting demurely holding a book.

Goddard’s pseudoscientific study of a southern New Jersey family, published in 1912, The Kallikak Family: A Study in the Heredity of Feeble-mindedness, examined the lineage of “Deborah Kallikak”, an inmate of the Vineland Training School (New Jersey) for the Feeble-minded, placing it in its historical context.

While the family name may have had the further stigmatizing effect of sounding ethnic, it was a creation of Goddard’s from the Greek κάλλος (kallos, “beauty”) and κακός (kakos, “bad”) to conceal the identity of his subjects.

Her actual name was Emma Wolverton. She could sew, woodwork, play several musical instruments and even cared for others at Vineland. Today she may be diagnosed with a learning or reading disability, but her greater sin was being an attractive single woman of childbearing years during a time when Victorian sensibilities ruled the day. Emma could not be trusted to her own devices, so she was removed from society for her own good.

Goddard was fond of creating titles. Moron (Greek: μωρός ‘slow, dull’), Imbecile (Latin: imbecillus ‘weak’) and Idiot (Greek: ἰδιώτης ‘person lacking professional skills’) were all scientific terms coined by Goddard to describe various levels of intellectual capability. And like the recent evolution of the term Retard[ed] (Latin: re- + tardus “slow”) as the terms entered the popular lexicon, they were informally used to attack the dignity of others and are no longer in use by the scientific community. In Goddard’s time The Kallikaks Family became a common reference that shaped generations of attitudes toward people who are considered to be different.

Employing vignettes throughout each chapter, Smith and Wehmeyer provide the reader with a comprehensive analysis of the Kallikak legend and its implications in digestible portions accessible to anyone. New source material allowed the authors to approach the story from several vantage points, making the 100-year old study fresh again.

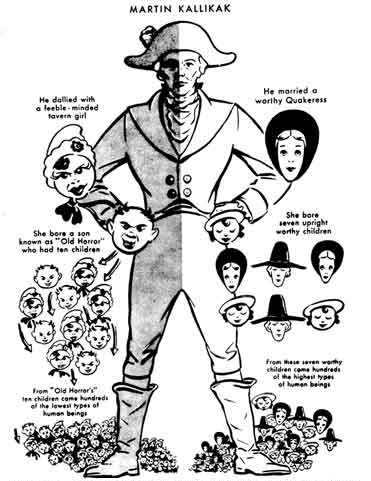

As late as 1961, this schematic visualization of the Kallikak myth was solemnly presented as a legitimate scientific concept in a widely used college textbook written in 1955 by the then chairman of the Columbia University Department of Psychology and revised six years later with the collaboration of psychology professor Hubert Bonner of Ohio Wesleyan University.

From Henry E. Garrett and Hubert Bonner, General Psychology (2nd rev. ed., New York: American Book Company, 1961).

Author J. David Smith is very familiar with this work, as his 1985 book, Minds Made Feeble: The Myth and Legacy of the Kallikaks, illustrates. In that work, Smith tracked down and reevaluated the true Kallikaks. When asked why, he replied, “It is, perhaps more than anything else, an illustration of the power of a social myth. Goddard found the characters that he could make fit the tale.” Smith illustrated in page after page how diagnoses of feeble-mindedness were shoehorned on otherwise talented individuals.

The Kallikaks Family was influential in the passage of compulsory sterilization laws in thirty states as well as the Immigration Restriction Act of 1924, which limited the number of Jewish immigrants who fled to America from Germany.

“The links between the American eugenics movement and Hitler’s murder of German people with disabilities,” Wehmeyer has said, “is able to be drawn firmly. The Kallikaks Family was also translated into German in 1914.” Goddard’s work was widely distributed in Germany in the 1930s. Shortly after the Nazis came to power, one of the book’s prime champions, Harry Laughlin, was given an honorary doctor’s degree by the University of Heidelberg.

“This isn’t a moral fable. It’s a true story,” said Wehmeyer, “This isn’t a story about a rogue scientist or evil people. This is a story about a mislead society.”

Smith added, “People with power and authority can have a huge influence on policy. We have to question authority.”

Both authors feel that Goddard did not maliciously corrupt his research. “Many people, including the US President and Supreme Court, accepted eugenics as scientific fact.”

CR