The Exorcist was the first one. Not the movie but a popular Polish magazine dealing with the science of casting the devil out of the human soul. I spotted it last year from my couch in LA on the Real Time with Bill Maher show on HBO. That was my first sighting of a Made-in-Poland-Seen-in-Mainstream-American-Culture phenomenon.

The Exorcist was the first one. Not the movie but a popular Polish magazine dealing with the science of casting the devil out of the human soul. I spotted it last year from my couch in LA on the Real Time with Bill Maher show on HBO. That was my first sighting of a Made-in-Poland-Seen-in-Mainstream-American-Culture phenomenon.

The next one was “Bring the Donkeys Back.” The donkeys lived in a zoo in Poznań, Poland, and they fell in love. Love in the donkeys’ world translates into having non-stop sex. But soon their free-style love enraged a female public official who filed a complaint against their public display of affection. They were playing by Mother Nature’s rules, but the politician insisted this exposed visiting children to obscene behavior. The donkeys ended up separated, the separation ended up in a massive public protest demanding: “Bring the Donkeys Back!” The donkeys were reunited, the story made world news and also made it onto the Rachel Maddow Show on MSNBC. My second Made-in-Poland-etc. phenomenon this year,” I thought to myself.

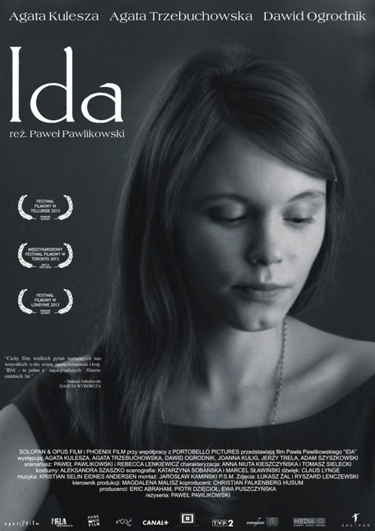

And then she came. “Have you seen Ida?” neighbors asked me at the dog run. Ida made it into the Hollywood Reporter, The New York Times, and everywhere else. “What’s that all about?” I asked myself, as I noted this third made-in-Poland phenomenon of the year. “It’s a black and white film about a Polish Catholic nun that America didn’t ridicule but fell in love with. Why?” This had to be checked out. No better sources than members of the Academy itself, so here are three opinions from cinematographer Steven Fierberg, producer James Katz, and producer Sara Risher.

Steven Fierberg

PHOTO: Agnieszka Niezgoda

Hollywood Place

Episode 1: Ida

Steven Fierberg, Cinematographer

Member of American Society of Cinematographers

Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Science.

(Love & Other Drugs; TV Series: The Affair, Entourage)

AN: What was your first reaction when you realized you were going to watch a black-and-white movie about a Polish Catholic nun?

SF: I didn’t know that. I just saw the movie not knowing anything. And then you see this nun, and the first thing that strikes you, as a cinematographer, is the framing. Which is very unusual. Radical. And it works for the story.

AN: Why is the framing unusual?

SF: They often put the human’s face either at the corner or at the bottom of the frame. For years, one of the things that they teach you at film schools in composition, in the convention of movie making, is that you set the top of the frame at the top of a person’s head. The idea that you would not do that seems radical. But to me, it immediately evoked the “Wow, look at what they are doing!” reaction. Nobody does that! And also, that film was framed in the old format, which is a relatively square framing. You don’t see that a lot, they did it in The Artist, as far as I can recall. It’s much more square than what we are used to now. Those two aspects were the ones I immediately noticed. And then: the beauty of the film, the lack of unnecessary dialogue. There is elegance in it.

AN: How does this unusual framing reflect the theme?

Still from Ida, dir. Paweł Pawlikowski

PHOTO: Opus Film

SF: Especially in the beginning, you are watching these nuns who pray, and you see the space above them, which implies the presence of God. The nuns are at the ground, the human is at the bottom, and the sky is up there. By attaching their heads to the bottom of the frame, it gives the message that they are attached to the earth. God is up there, and we are here on the earth.

AN: Wasn’t this radical beauty of the aesthetic a distraction in focusing on the story?

SF: Not at all. I used to think that Ida is a sad, dark story that needed to be uglier. But it’s really not true about the greatest films. When you look at the history, great films that are extremely dark, they also can be extremely beautiful. Another unusual aspect for a cinematographer is that they do both close-ups of this beautiful, photogenic girl, and a lot of wide shots. When she first meets her aunt – in America there is no way you would not do both close-ups on them. In Ida, instead, they are back in a stairway, and you are watching them full length. Cut to the next shot, which is also full-length, when she enters into an apartment. You could argue that that’s distance, which takes a viewer away from the story. But the film is still really emotional.

AN: Did you connect to the story? What was it about?

Still from Ida, dir. Paweł Pawlikowski

PHOTO: Opus Film

SF: Very much. I don’t know the filmmaker but I can see him as being Catholic and believing in it. Here is this girl, she is growing up in paradise, and she is forced out of it, and acquires knowledge of the world. And there is her aunt, sleeping with everybody, and alcoholic, crushing the car, all these dark things, and the horrific things about people being killed. And at the end the girl, who tasted the world, runs back to the Garden of Eden. It’s interesting because it doesn’t take a judgmental point of view like, “Oh, those nuns, they are all just square idiots,” like her aunt thinks. There is something beautiful about the life that she has there. And in the outside world there is suffering, there is pain.

AN: Which trait in our protagonist makes us connect to the role of a young nun?

SF: There is decency about her. She tastes her aunt’s world, she is not uptight, but at the end she follows her inner road marks. She is honest. She is virtuous. She is a good person. A Catholic nun, but a good version of a nun.

AN: How did you see Polish-Jewish relations depicted in this film?

SF: It’s presenting the anti-Semitism that still exists; to some extent, in contemporary Poland. The town is so uncooperative. But maybe they are just protecting the people they know? This family on the one hand was trying to help them, and then, at the end, they had to kill one of them, a child, to save the other. That’s as dark as human behavior gets. Perhaps from the guy’s perspective he did the right thing? And probably he was a decent guy, and suddenly he is put in a position when he has to kill a baby… This horror, what happened there… Being an American it’s hard for me to imagine. This Jewish-Catholic world of that time is horrific. The movie portrays it in a really sensitive and fair way.

AN: How does the cinematography reflect this emotional ending?

SF: The camera doesn’t move until the end. And when she is running back, it becomes very active, energetic, very much into your face. The director saved this intense camera motion for the climax. The camera becomes more passionate when she heads back, as if it was shouting: “That’s it, I am done with this world! Back to paradise!” I thought the movie was great.

James Katz

PHOTO: Agnieszka Niezgoda

Hollywood Place

Episode 2: Ida

James Katz, Producer

Member of the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Science and the Foreign Language Committee

Former president of the Universal Classics division

AN: You watched Ida long before it became such a blockbuster. What was your first reaction to what you’d seen?

JK: I ran a division in Universal for many years; it was the first classics division in a major Hollywood studio. And I looked at films all the time. I would have come at 9 am, and I had no idea what I was going to see. I just knew where it came from and the name of the filmmaker. So, to me, seeing a film without preconceived ideas is really great. Now, when we know that Ida is a success, that the film is nominated, that it’s controversial, I couldn’t be as objective, as I was before. So I started watching it with my wife, Marty, and I was taken aback immediately. Black and white, I didn’t expect that. I didn’t know it was about a nun. I didn’t know anything, but we totally got into the story. The personal story of a woman. And then the environment in which it was shot, it didn’t give away very much. Eventually you learned that the story takes place in the 1960s, but the monastery scenes could have been in the 1930s. You just see they live in poverty, they are cooking soup for everybody, you get the power structure early on, and so much happens so quickly. You immediately get the idea of what she was dealing with. So I got into the story quickly, and I thought “Wow!” I am an old guy; I saw Knife in the Water, and all of the early Polański movies. I saw the early Skolimowski and Zanussi movies. I always loved those.

AN: Did you see a clear connection between Ida and these Polish classic films?

JK: Oh, yes. I lived in Europe in the 1960s, and I was very tuned into those films, because when I was working at United Artists we had a division which specialized in bringing those black-and-white films: French, Greek, and Polish: from all over Europe to Hollywood. So it was really a novelty for me to see Ida in black-and-white. It was very reminiscent of that period. If you took Paweł Pawlikowski and put him back into the 1960s to make films, he would perfectly fit into the style. Which was imposed to a degree by what was available back then.

AN: Was the black-and-white shot the only layer of connection, or were there others?

Still from Ida, dir. Paweł Pawlikowski

PHOTO: Opus Film

JK: The whole thing. It was about someone, someone’s personal story. The structure was really sound. The storytelling was solid. The performances were amazing. The actress who played the girl’s aunt was outstanding. The background, the time period, perhaps wasn’t that clear. Some Hollywood filmmakers say this should have been more of a factor: that Poland was under German occupation, and then the Russians came and took over. But I am sort of wrestling with it now… It was clear that the story was taking place under the communist regime in Poland, but I don’t think they made a point of the big picture. And yet I thought about it, and I say, you know, it really doesn’t matter. It’s really about this woman and her journey. It can be a metaphor for so many things. It could be somebody dropping out and having one last chance to get into the world and face what one has to face these days.

AN: Did it resonate with you on the personal level?

JK: Not so much, I was never cut off from the rest of the world, perhaps except for a while when I was serving in the military. I didn’t identify with her character that way. But the film was so well-done; I had not been familiar with the director before.

AN: What was the image of Polish-Jewish relations that Ida brought to you?

JK: Well, it didn’t matter whether it was Nazis or communists, Jews were not particularly welcome in Poland, which has always been such a broadly Catholic country. But to me it doesn’t reflect Poland so much, as it reflects the occupiers. The fact that she had a Jewish past was important to the story, it was another layer on the film. She was no better off being Jewish with the Russians, than she would have been with the Germans.

AN: Some people in Poland had an issue with Ida’s alleged anti-Polish context.

JK: I don’t understand, why would the Poles have an issue with that?

Still from Ida, dir. Paweł Pawlikowski

PHOTO: Opus Film

AN: Toward the end her aunt brings her over to their old home village, which is mostly inhabited by the hostile newcomers.

JK: That’s the point. The newcomers. And who are they? You don’t really know that. You just know that they took over the property. You’ve got to get outside of yourself, whether you are Jewish, or Polish, or German.

AN: You are a member of the Foreign Films Committee at the Academy. Has there been any major change in the submitted foreign films over the course of the last few decades?

JK: A crucial one. Years ago, if you had a film and you were from a Third World country, Sierra Leone or Malawi – and I am not saying that Poland belongs to this category – you could have a great script, great actors, great director, but you would still be taking VHS and transferring it into film. And it would look like crap. Now it doesn’t matter where the films are coming from, they all look good, because anyone can afford a digital camera that will at least give you the proper resolution, so the visual is no longer a distraction. The quality is very crisp, so you judge the film based on its story and filmmaking. And in the middle of all this, bam! Black-and-white film, bleak, with a story set in a depressing atmosphere, depicting a repressive time.

AN: And you, Americans, you hate this Polish love for a depressing atmosphere!

JK: But it was refreshing! We are dealing with stereotypes. I was in Poland several times, for the first time in the late 1960s. I had this idea that it was always dark in Poland, this frame of reference from Polański’s and Skolimowski’s black-and-white films. And I landed in Warsaw, and got off the plane, looked around, and it was beautiful! The sun was out, the squares were green, and the planting was lush. The first impression was really nice. I went to the Łódź Film School – at this time Polish movie posters were very creative – to speak about poster as an art form, and about selling the script to actors and to the studio, about the process from the first to the last days of shooting, postproduction, marketing, and how you have to sell the picture to distributors.

AN: That must have sounded pretty exotic back then to Polish students.

JK: It was unbelievable. Their frame of reference was so different.

AN: Did Ida give you nostalgia for those old days?

JK: Of course. The Academy is made up of members of an average age around 60 years old. I am in my seventies, and there are some people older than me in the Academy, and that’s definitely a point of reference to our mutual experience. Black-and-white shots set the tone. It serves a really interesting story about a young girl who came to a crossroad. As we all can come to at some point in our lives.

Sara Risher

PHOTO: Agnieszka Niezgoda

Hollywood Place

Episode 3: Ida

Sara Risher, Producer, Member of the Academy

Executive Achievement Award 2007

Has supervised the production of more than 50 feature films

AN: Was there anything personal that you related to in Ida?

SR: Several layers. First of all, I was overwhelmed by its minimalism. The photography, the black-and-white, the simplicity. I was a part of that world. But also, I could relate to both of the women.

AN: What did you relate to in the two characters of Ida and her aunt? They were completely opposite. A young, Catholic nun versus her aunt, who was a former Stalinist prosecutor, sentencing people to death?

SR: I don’t feel critical of either one of them. I was a Latin Catholic, so I understood the concept of the convent, and the nuns, and the beauty of that. I respect those women, I have a great admiration for their choice. But by rejecting my religion I became more of a woman seeking outer life, because I feel that what is the most important happens right here, in this world, not in the afterlife. So I admired the aunt’s passion. Women don’t have a lot of choices: they had even fewer back then – so I think she fought her way through life. She had strong, radical points of view that I don’t necessarily agree with but I admired her fighting spirit. Her lust for life.

Still from Ida, dir. Paweł Pawlikowski

PHOTO: Opus Film

AN: You don’t support her moral choices, but you admire her character’s pattern of being an empowered, bold woman, who was hiding her suffering, her pain deep down?

SR: Yes. Her suicide really hurt me. I thought she was stronger than that. As for Ida, I shared her faith because I had it too when I was young. But to me life is more about opportunity that she had: to have love, and family, and friends. But she let it go. She chose otherwise, she chose solitude. So when I met the director I told him: “I think she made the wrong choice.” And he answered: “How do you know?” It was a very female story. A story of two women.

CR

Pingback: Welcome to our Spring 2015 issue!

“Wasn’t this radical beauty of the aesthetic a distraction in focusing on the story?”

In my opinion, the beauty of the film only serves the story, because it makes it easier on the spectators to digest the difficult details that the story conveys. In a way, the aesthetic merits of the film help to surpass the numbness that humans tend to sink into when exposed to difficult stories.

Pingback: Welcome to Summer 2015!