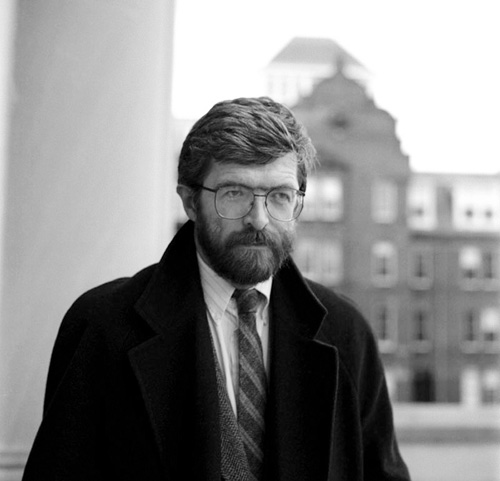

Joanna Trzeciak

PHOTO by Daniel Levin

Joanna Trzeciak, a native of Poznań, Poland, is Associate Professor of Russian and Polish Translation at Kent State University in Ohio. Trzeciak’s translations of Polish and Russian poetry have appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Atlantic Monthly, The Times Literary Supplement, Harper’s, and The Paris Review, among others.

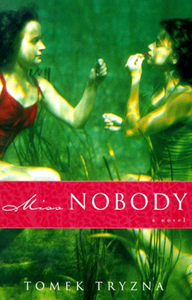

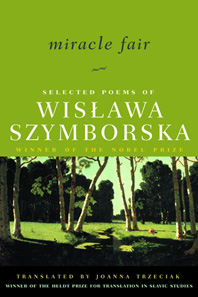

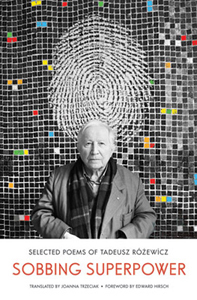

In 1998, Doubleday published her translation of Tomasz Tryzna’s acclaimed novel Miss Nobody (Panna Nikt). Four years later, W. W. Norton & Company published Trzeciak’s Miracle Fair: Selected Poems of Wisława Szymborska, which was awarded the Heldt Translation Prize. Her second book of poetry translations, the 2011 Sobbing Superpower: Selected Poems of Tadeusz Różewicz was awarded the best scholarly translation into English by the American Association of Teachers of Slavic and East European Languages. It was also the winner of the 2012 Found in Translation Award, and was shortlisted for the prestigious Griffin Poetry Prize in Canada.

Ross Ufberg, a translator and participant in one of Joanna Trzeciak’s recent workshops, praised her translation expertise in the following terms: “To sit with [Joanna Trzeciak] and watch her take apart one of my translations – it was like handing an old clunky thing to a master watchmaker and watching as the expert made the timepiece run so much more smoothly.” In the interview below, Trzeciak unveils the art of poetry translation and in particular her experience translating the Nobel laureate Wisława Szymborska and Tadeusz Różewicz, who passed away in Poland this April at the age of 92.

* * *

Agnieszka Tworek: What inspired you to become a translator?

Agnieszka Tworek: What inspired you to become a translator?

Joanna Trzeciak: That was born of a desire to share an aesthetic experience. The first poet I translated was Szymborska. At the time I started, many of her poems were not available in translation. Initially I did it for my friends but then the circle widened.

AT: To give us an idea of your process, could you talk about one particularly tricky problem you encountered in one of your translation projects—a word, a phrase, a section, or an entire text—and how you were able to resolve it in the end?

JT: These kinds of challenges arise often, and it helps if you are open to taking chances and risks. A salient example of a translation problem I encountered was one that arose in “Nadmiar” (“Surplus”), a Szymborska poem which draws upon the contrast between the earthly and the cosmic. The setting of the poem is a little celebration among astronomers (and their circle) of the discovery of a star. One of the munchies on hand are peanuts (orzeszki ziemne, which translated literally would be either “earth nuts” or “ground nuts”). It is Szymborska’s gentle way to make concrete, among other things, the earthbound concerns of human beings, astronomers included. The problem is that the English “peanuts” lacks the terrestrial tug of “orzeszki ziemne.” Hence I decided to substitute “terra chips.” Translation is situated in a given time, and luckily that possibility was available to me. I hope Terra Chips are here to stay. They’re delicious.

JT: These kinds of challenges arise often, and it helps if you are open to taking chances and risks. A salient example of a translation problem I encountered was one that arose in “Nadmiar” (“Surplus”), a Szymborska poem which draws upon the contrast between the earthly and the cosmic. The setting of the poem is a little celebration among astronomers (and their circle) of the discovery of a star. One of the munchies on hand are peanuts (orzeszki ziemne, which translated literally would be either “earth nuts” or “ground nuts”). It is Szymborska’s gentle way to make concrete, among other things, the earthbound concerns of human beings, astronomers included. The problem is that the English “peanuts” lacks the terrestrial tug of “orzeszki ziemne.” Hence I decided to substitute “terra chips.” Translation is situated in a given time, and luckily that possibility was available to me. I hope Terra Chips are here to stay. They’re delicious.

AT: When you read a translation by another translator that you find compelling, how do you know it’s good? What draws you to it, if that’s something definable?

AT: When you read a translation by another translator that you find compelling, how do you know it’s good? What draws you to it, if that’s something definable?

JT: You can usually spot an inspired translation. You know something is good when you feel a tingle down your spine, when a poem really moves you, even in translation. The translator may access something that wouldn’t even have been possible in the source language, but is lurking in the language that he or she is translating into, the target language. Inspired translations make maximal use of the expressive possibilities in the target language and culture. The translated work ceases to be merely a translation, and becomes a work of art.

Wisława Szymborska

AT: You began to translate Wisława Szymborska in 1988, eight years before she received the Nobel Prize in Literature. How did you meet her and what attracted you to her poetry?

JT: No one has been more important in this respect than my father, a biochemist and molecular biologist, who read to me and encouraged me to write poetry. When I was eleven, I sent a whole bunch of poems to Szymborska, who humored me by writing me back. We corresponded off and on over the years. When I was already in the States, I decided to translate her poetry, and to analyze the process I used, for my BA thesis in English literature. But first I had to argue before the English department that she was a major poet. Szymborska has a very distinctive voice. As a child I loved the elegance of her diction, and I still do. But with time I have come to value her humanism, her irony, her subversiveness, her refusal to speak for others, the economy of her verse.

AT: When you were an adolescent, you were not fond of Tadeusz Różewicz’s poetry. You said that he was your father’s poet. What motivated you to translate Różewicz and how did you approach him about it?

Tadeusz Różewicz, Konstancin, 2008

PHOTO by Elżbieta Lempp via Culture.pl

JT: I was always fond of Różewicz’s poetry. I simply did not understand him the way I understand him now. Różewicz is a very demanding poet. There are a number of layers to Różewicz, though when you access even one layer, there is a lot there. However, the more you read, the more you see. It really helps to read all of his poetry, his plays, his stories, and his essays. Then you start to see his work as a whole, and it becomes unquestionable that he is one of the great poets of the twentieth century.

In graduate school, once I read a decent dose of Różewicz, things began to click. I was very taken by the 1998 volume recycling and especially the title poem, which offers a diagnosis of the state of our civilization. That’s when I started to think about translating him, but I felt it was important to meet him before fully embarking on the project.

Next time I was in Poland, and in Wroclaw, an editor of Różewicz’s works, Jan Stolarczyk, drew me up a map of Różewicz’s daily walk in Park Południowy, and I set out in the opposite direction, so that I might chance to meet him coming the other way, and I did. For a good hour, we sat on a bench and talked, mostly about art (Różewicz was quite engaged with the visual arts starting in the late 1940s, and understood it like no other contemporary poet. Moreover, he was able to transform the language of the visual arts into the language of poetry). To continue our conversation I would call him on the phone, and introduce myself as “Joanna from the park.” He didn’t know my last name until I started publishing translations. When after a couple of years I approached him about a book, he felt like he was in safe hands.

Tadeusz Różewicz’s poem “Pisalem” (“I wrote”)

on a wall of a building at Oude Vest 79, Leiden, The Netherlands

PHOTO by Tubantia via Wikimedia Commons

AT: Edward Hirsch in his introduction to Sobbing Superpower, your book of translations of Różewicz’s poems, wrote that you capture Różewicz’s “cunning style of negation, his stark diction and sudden turns, his talkativeness, his well-timed silences, his artful artlessness.” Were the challenges of translating Różewicz different from the challenges of translating Szymborska?

JT: Translating a poet involves hearing the poet’s voice and finding a way to capture it in another language and culture. Both Szymborska and Różewicz are universal poets: they can reach anyone. But the difference is that Szymborska tends to do so in ways that are less reliant on cultural and intellectual touchstones. Różewicz alludes to the philosophy of Hume, Kant, Lichtenberg, Nietzsche, Wittgenstein, Heidegger, Ingarden, and engages with them in sophisticated ways, and that often requires a gloss. Same goes for Beckett, Kafka, Pound, Celan, Celine, Rilke, and Gottfried Benn. Not to mention the visual artists, Francis Bacon, Tadeusz Brzozowski, Xawery Dunikowski, Alina Szapocznikow, Jerzy Nowosielski, and Andrzej Wróblewski, to name just a few. Thus, in my translations of Różewicz I have had to rely a lot more on paratext, or notes to the poems, than I have needed to do in my translations of Szymborska. Otherwise, the main difference is that Różewicz was actively creating a poetics and a language that made it possible for Szymborska and other poets to write poetry in the postwar period. Every major Polish poet has acknowledged how important he was in that regard. I tried to capture his daring in English, but at times his simple diction may be mistaken for artlessness. Edward Hirsch has emphasized that the artlessness is an illusion, which is exactly right. Szymborska is a very graceful poet, and that is the most important thing to convey.

AT: How has your teaching informed or been influenced by your translation work?

JT: I teach translation theory, and I find it helpful to be grounded in theory. Understanding theory can help you be a closer reader of texts. Different theories offer different readings of the text, and may help you come up with an appropriately conceived goal for your translation. I am not saying that you have to be a theoretician to be a good translator, but it certainly helps you think about what you are doing, articulate your approach, and justify your choices. It is often disappointing to listen to translators who aren’t conversant in translation theory talk about translation, although you might value and enjoy their actual translations.

AT: Who is next? And do you have any other creative projects?

JT: I am working on an anthology of twentieth century Polish poetry in my translation. It will probably include over forty poets. Poland has produced so many great poets. The anthology is an enormous undertaking, but it’s such a pleasure to be reading their work. I have already been able to secure the publication rights for some of the poets. As for other projects, I am working on a couple of plays, but I do not want to say anything more about that till they are completed.

CR

A new star has been discovered,

which doesn’t mean it’s gotten any brighter

or something missing has been gained.

The star is large and distant,

so distant, that it’s small,

even smaller than others

a lot smaller than itself.

Surprise would be nothing surprising

if we only had time for it.

Star’s age, star’s mass, star’s position,

all of that may be enough

for one doctoral thesis

and a modest glass of wine

in the circles close to the sky:

an astronomer, his wife, relatives, and colleagues,

a casual ambience, no dress code,

local topics fuel a down-to-earth conversation

and people are munching on Terra Chips.

A wonderful star,

but that’s still no reason

not to drink to the ladies,

incomparably closer.

Star without consequences.

Without influence on weather, fashion, the score of the game,

changes in government, income, or the crisis of values.

With no effect on propaganda or heavy industry.

Without reflection in the finish of the conference table.

An excess number for life’s numbered days.

Why need we ask

under how many stars someone is born

and under how many they die a little while later?

A new one.

“At least show me where it is.”

“Between the edge of that jagged grayish cloud and the twig of that locust tree on the left.”

“Oh,” I say.

–Translated from the Polish

by Joanna Trzeciak

from Miracle Fair (W.W. Norton, 2001)

Tadeusz Różewicz

the Middle of Life

After the end of the world

after my death

I found myself in the middle of life

creating myself

building a life

people animals landscapes

this is a table I kept saying

this is a table

on the table are bread knife

the knife is used for cutting bread

people feed on bread

man should be loved

I learned by night by day

what should one love

I answered man

this is a window I kept saying

this is a window

beyond the window is a garden

in the garden I see an apple tree

the apple tree blossoms

the blossoms fall off

fruit forms

ripens

my father picks an apple

the man picking the apple

is my father

I was sitting on the front steps of the house

that old woman

pulling a goat on a rope

is more needed

is worth more

than the seven wonders of the world

anyone who thinks or feels

she isn’t needed

is guilty of genocide

this is a man

this is a tree this is bread

people eat to live

I kept repeating to myself

human life is important

human life has great importance

the value of life

exceeds the value of every object

man has made

man is a great treasure

I kept repeating stubbornly

this is water I kept saying

stroking the waves with my hand

talking to the river

water I said

kind water

it is I

the man talked to the water

talked to the moon

to the flowers to the rain

he talked to the earth

to the birds

to the sky

the sky was silent

the earth was silent

if he heard a voice

flowing

from the earth the water the sky

it was the voice of another man

–Translated from the Polish

by Joanna Trzeciak

from Sobbing Superpower (W.W. Norton, 2012)

Pingback: Welcome to our Summer 2014 issue!

Each article by Agnieszka Tworek opens a window to yet another aspect of Polish culture unfamiliar to me. Thank you.

Grateful if you send me your postal address.

Please email editor@cosmopolitanreview.com with any questions or comments.