Would Vegas be Vegas without block after block of dancing, shimmering neon signage? Would Times Square?

Would Vegas be Vegas without block after block of dancing, shimmering neon signage? Would Times Square?

And what about communist-era Warsaw?

Not according to Eric Bednarski’s newest documentary, NEON, in which he traces – as fluidly as an artist shaping delicate neon tubing – the arc of this signage across 20th century Poland.

“I wanted to make another film about Warsaw,” Eric tells me via video chat from his Warsaw apartment. “Specifically, about the Warsaw of the 60s and 70s.” To do so, he chose neon signage in the Polish People’s Republic, telling a story that’s not widely known in Poland or abroad.

That story is not without controversy. The first neons adorned late 1920s Warsaw, a vibrant, teeming European capital filled with the promise of freedom. Neons reappeared after WWII, but in a different context, one that was state-sanctioned and highly regulated. They were beautiful and inventive, but also represented the oppressive communist regime. “Neons didn’t arrest people or execute people or ruin people’s lives,” Eric says. “But they were part of a system that did.”

The film begins with Ilona Karwinska, a neon collector and co-founder of the new Neon Museum in Warsaw. She walks around a large warehouse filled with neon signage, its glow gently illuminating her face. Born in Poland, she left for London in 1991, returned in 2005 – and noticed how quickly Warsaw’s neons were disappearing. She began photographing, and then collecting them. Along the way, she came into contact with Reklama – the main producer of Warsaw’s neons during the communist era.

Reklama’s former director Jacek Wyczółkowski says that during its heyday in the 1970s, the company produced a dozen or more neons a month. Neons were state-sanctioned like every commercial endeavor during the communist era. Wyczółkowski takes us through the exhaustive approval and acceptance process of the neon’s design: Each step required multiple signatures, seals, stamps, committees.

Reklama’s former director Jacek Wyczółkowski says that during its heyday in the 1970s, the company produced a dozen or more neons a month. Neons were state-sanctioned like every commercial endeavor during the communist era. Wyczółkowski takes us through the exhaustive approval and acceptance process of the neon’s design: Each step required multiple signatures, seals, stamps, committees.

One of Eric’s favorite surprises during the making of the film was discovering the Reklama archive. “They had pretty much every neon that was made,” he says. Folders for each neon included a 1:1 scale drawing and photographs. The documents, stored in a moldy storage space, were in terrible condition, but “they were incredible, because not only did they show the technical drawings for each neon, you could follow the electrical details of the buildings as well,” Eric says. “So I went through the history of the city in the 50s and 60s and 70s by going into these files.”

By the end of WWII, Warsaw was destroyed almost entirely. And the city that rose after 1945 did so under communist control and according to a Soviet vision. It was a city with no space for advertising, we learn from writer Marek Nowakowski, because there’s no space for commerce in this new communist sphere.

But in the 1950s, that hold thawed a bit. And artists and designers were afforded a bit of freedom, journalist Jerzy Majewski tells us. It’s into that space that neons return, their light and artistry offering a physical and psychological lift to a city still reeling from destruction and a dull, utilitarian rebuild.

But in the 1950s, that hold thawed a bit. And artists and designers were afforded a bit of freedom, journalist Jerzy Majewski tells us. It’s into that space that neons return, their light and artistry offering a physical and psychological lift to a city still reeling from destruction and a dull, utilitarian rebuild.

As archival footage of brightly-lit Vegas and New York splashes across the screen, neon designer Piotr Pereplys says: “We felt that we were part of the larger world.” They weren’t. And the neons show us why: Communist neons never advertised. They informed: Maszyna do Szycia. (Sewing Machine.) Dancing. Delikatesy. Drogeria (Pharmacy). Instead of brand advertising like in the West, you’d see a single word informing what was [supposedly] in the store: Meat. Lamps. Food. Bar. And that’s another reminder of how cut off Poland and the Soviet Bloc were: A store with an elaborate Meat neon would often have empty shelves and empty hooks.

In a black-and-white clip, a cheerful announcer urges his audience to lift their eyes up from their everyday troubles – and instead, look at the neons. “The neons shone amid the grey, sad reality,” Pereplys says.

Poland’s political and economic situation never improved. In the 1970s, the failing economy would trigger the Polish Solidarity movement. A decade later, that increasingly powerful democracy-seeking movement was too much of a threat for Moscow, which imposed martial law in 1981.

Here, too, the neons played a role: When martial law was announced on Dec. 13, 1981, all Warsaw’s neons were ordered off permanently. Darkness and cold – physical and metaphysical – were complete. Their electrical components fell into such disrepair that when authorities decided they could be switched back on, the majority no longer worked. “The great illuminating promises of the 50s,” historian David Crowley tells us, “had evaporated.”

Here, too, the neons played a role: When martial law was announced on Dec. 13, 1981, all Warsaw’s neons were ordered off permanently. Darkness and cold – physical and metaphysical – were complete. Their electrical components fell into such disrepair that when authorities decided they could be switched back on, the majority no longer worked. “The great illuminating promises of the 50s,” historian David Crowley tells us, “had evaporated.”

What room, then, was there for neons in a post-communist world? They represented a hated past regime. And they began to disappear as early as 1991 – the same time, Crowley says, that advertising in the Western sense exploded across Poland, and especially Warsaw. Suddenly, advertising was everywhere, bringing what he calls a “visual chaos.” Huge banners covered the facades of historic buildings, and “the city was losing its identity.” The public sphere, once so tightly regulated and controlled, was now awash in brand advertisements. More and more neons came down.

Looking at the footage showing one such sign being disassembled, I find myself having the strangest reaction: I loathe communism! It nearly wiped out my homeland. And yet – watching the neon come down, bit by bit, makes me sad. This, perhaps is the crux of Eric’s film: Can those feelings be reconciled?

“That is a theme that comes up a few times in the film,” Eric says when I ask him about reconciling past and present. “Obviously, the communist system was terrible and I’m not an apologist. At the same time, you can’t dismiss it all and destroy it all and say it was all terrible because these were world-class artists and architects.” For Eric – neons hold artistic value but he also notes that they have not been de-politicized for everyone.

“That is a theme that comes up a few times in the film,” Eric says when I ask him about reconciling past and present. “Obviously, the communist system was terrible and I’m not an apologist. At the same time, you can’t dismiss it all and destroy it all and say it was all terrible because these were world-class artists and architects.” For Eric – neons hold artistic value but he also notes that they have not been de-politicized for everyone.

His film ends as it began – with Ilona, whose collection of 70 or so neons has now been moved into the new Museum of Neon in Warsaw (she’s a co-founder). Familiar neons – we’ve seen them in black and white or washed-out archival footage throughout the film – now adorn the walls of the museum. Some are lit. Some flicker. Some remain dark.

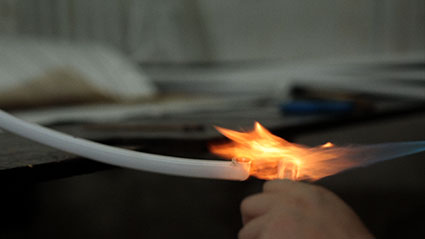

We also see a ceremony celebrating the renovation of a neon with the name of a former train station. It now lights up a new space, a cafe and meeting spot with plenty of outdoor seating that draws crowds. And we also see new neons being produced, gently lighting Warsaw facades and streets again.

We also see a ceremony celebrating the renovation of a neon with the name of a former train station. It now lights up a new space, a cafe and meeting spot with plenty of outdoor seating that draws crowds. And we also see new neons being produced, gently lighting Warsaw facades and streets again.

CR

NEON was released this May in Poland and co-produced with Culture.pl and Telewizja Polska.

WATCH the trailer:

CR

Pingback: Welcome to our 2014 Fall-Winter Issue!

Really interesting!

Pingback: Fall-Winter Version of the Cosmopolitan Evaluate | Posts