Panorama of Budapest.

From left to right: The Castle Hill (Várhegy),

the Chain Bridge (Lánchid) that spans the river Danube,

and the dome of the Hungarian Parliament Building.

My first trip to Hungary was in 2002, and upon arriving at Budapest’s Keleti Pályaudvar, or East Train Station, I was prepared for culture shock. As my guidebook explained, the tribe of Hungarian people, or Magyars, had arrived in the Carpathian Basin from the steppes of Central Asia in the year AD 896, and had managed to make a home for themselves amid the sea of Slavonic peoples. Speaking a completely different language, this isolated island of Magyars often had to fight to survive, an experience described by the writer Arthur Koestler as an “exceptional loneliness.”

Arriving from Poland, where I had been studying Polish language and culture, I had a strong appreciation for those small nations of Europe that had been swallowed and subsumed by the great Empires of the past, whether the Ottoman, Austrian, or Russian. In any case, I was eager to learn about the history of Hungary and the secret of how this small nation had managed to outlive all of those Empires that had attempted, and ultimately failed, to conquer her.

Budapest’s East Train Station (Keleti Pályaudvar) on an old postcard.

My group and I had decided to hire out a tour guide from a pamphlet taped up in our hostel. We met in Deák Tér on the Pest side of the Danube, which, though I had not known at the time, was named after Ferenc Deák, architect of the 1867 Compromise that had resulted in a Dual Monarchy that shared power between Vienna and Budapest. The Compromise was almost inevitable, as the Hungarians had demonstrated two decades earlier, in 1848, that they were willing to fight and die for the freedom of their country, to the great consternation of the Austrians who ruled over them. 1848 was an auspicious year that saw uprisings not only in Hungary, but indeed, throughout Europe.

A tablet commemorating Józef Bem, Budapest.

Ferenc Deák was himself quite mindful of the failed Kraków Uprising against the Austrians in 1846, which had lasted nine days and resulted in the deaths of at least one thousand Polish patriots. Many of those who survived had crossed the border into exile in Hungary. Among the exiles was the Polish revolutionary Józef Bem, who had led troops during the 1830-31 November Uprising in Poland. Following the defeat of the Poles, Bem had joined that illustrious family of Polish exiles in what was known as the ‘Great Emigration,’ travelling to Paris, and later to Portugal, assisting in the revolutionary cause and narrowly avoiding an assassination attempt by Russian agents.

In 1848, Bem arrived in Austria and played a major role in the Vienna Uprising, which was triggered by riots against Austrian troops marching en route to suppress the Hungarians. Although Bem survived the uprising in Vienna to eventually fight alongside the Hungarians, many of the leaders of the insurrection would be executed, foreshadowing what was later to come in Budapest.

Hősök Tere, or “Heroes’ Square,” in Budapest. A statue of the Archangel Gabriel holding the crown of St.Stephen tops the center column. A depiction of Árpád, founder of the Hungarian nation, is at the base. Statues of historic rulers in Hungarian history are on both sides.

We boarded the metro, the yellow line, towards Hősök Tere, or Heroes’ Square, which is located near the zoo and somewhat out-of-the-way from the Danube promenade, the fashionable Váci Utca, and more central attractions. It was a cold, overcast and blustery day, and as we quit the metro—the second oldest on the European continent—we approached a vast open space at the end of which stood a semicircular shrine to the Hungarian kings with a tall column crowned with the figure of the Archangel Gabriel bearing the holy crown of Szent István, or St. Stephen, the first king of Hungary.

Our tour guide was an older man, and I wondered if he had been around to witness the 1956 Hungarian Revolution against the Soviet occupation, which as I later learnt, had coincidentally begun at the foot of a statue commemorating Bem Apó, or Grandpa Bem, which was located on the Castle side of the Danube. I never asked our guide, though he was certainly aware of the great significance of this place for Hungarians, and which is why he brought us there first.

A statue of Imre Nagy (1896-1958) gazes at the Hungarian Parliament Building. Nagy was executed by the Communist authorities for his role in the 1956 Hungarian Revolution.

Built in 1896 to commemorate the one thousand year anniversary of the Magyar Honfoglalás, or arrival of the Magyars into the Carpathian Basin, Hősök Tere had, during the tumultuous twentieth century, seen the proud faces of Hungary’s kings completely covered by portraits of Lenin and red textile during the 133 days of the Hungarian Soviet Republic following the First World War. Hungarians, however, would eventually would have the last laugh when, following nearly half a century of Soviet occupation after World War Two, over 100,000 people, including many exiles from the 1956 Revolution, would gather in the square to pay homage to Imre Nagy, a former communist politician who had sided with the people during the Revolution and had paid for it with his life. For myself, it was evident that the Hungarians, like the Poles, shared a common history of martyrdom, revolution, mourning, and a thirst for freedom that helped unite these two peoples, separated by language and origin, into a brotherhood of common fate and destiny.

This sense of a common destiny between the Poles and Hungarians, as two proud nations that each suffered frequent incursions by aggressive neighbours, can be seen through the strong ties forged between them over the ages as well as through their willingness to aid each other in times of need. One of the most famous examples of this bond occurred during World War Two after Poland had been occupied by Nazi Germany and more than 100,000 Poles fled to Hungary, either to spend the remainder of the war or, in most cases, as a temporary stopover on their way to continue fighting with the Western Powers.

Hungary, at the time, was under great pressure by Nazi Germany to cut off diplomatic relations with Poland and to turn over many of the fleeing Poles to German authorities. The Hungarians intentions however were very much summed up in a letter to Adolf Hitler by Prime Minister Pál Teleki, in which the latter stated that it was a question of Hungarian honour not to engage in any aggression or acts of harm against the Poles. Another quote attributed to Teleki declared that he would rather destroy Hungary’s own rail system than join the Germans in an invasion of Poland.

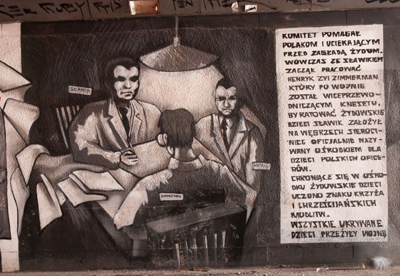

Part of a graffiti mural in Katowice, Poland: Henryk Sławik

sits with Zvi Zimmerman and József Antall.

They’re working on saving the lives of

escaping Polish and Hungarian Jews through

setting up a network of orphanages.

The Hungarian authorities provided the Polish refugees not only with legal protection, but also with supplies, food, and even a monthly living allowance. One of the most important figures in the resettlement of the Poles in Hungary was Henryk Sławik, who was the head of the Citizen’s Committee for Help to Polish Refugees. Sławik, a politician and labour activist who had been spotted by József Antall, the Hungarian Minister of the Interior, in a refugee camp shortly after crossing the Carpathian Mountains into Hungary, was later responsible for setting up Polish orphanages and schools throughout the Danube region as well as saving the lives of thousands of Jews by placing them in communities run by Catholic nuns. Writing about these years in Hungary, Sławik noted that:

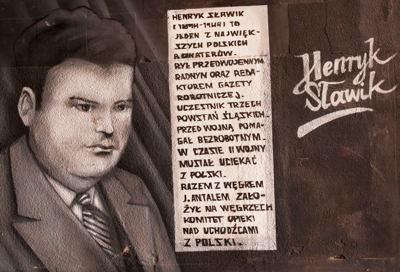

Part of a graffiti mural in Katowice, Poland that depicts Henryk Sławik.

“As our feet once again touch the holy ground of our motherland, many of us will look back fondly at the hospitality that we received on Hungarian soil, which took us in and sheltered us for so many years. We understood at that moment, that this was not a foreign land, but the country of our eternal friends, who in difficult and dark hours did not abandon us and courageously, in accordance with the dignity of this honorable people, helped us survive the most difficult trials of our spiritual and physical exile. Every layer of this people, great and small, remained our companions through our misfortune. We encountered many warm friends here, so many that one could not believe…We will not ever forget about them.”

The Hungarians were also there to assist the Poles at the end of the war. Amazingly, during the Warsaw Uprising, Hungarian troops nominally allied with the Germans provided substantial aid and supplies to the Poles and there are reports of Hungarians switching sides to fight alongside their Polish brothers and sisters. Indeed there were many efforts by Hungarians to switch sides during the war, a tendency noted by the Germans who warned the Hungarians multiple times against joining the fight alongside the Poles. Among Hungarians who fought in the Warsaw Uprising is József Vonyik, buried together with six unidentified comrades in a Warsaw grave.

Stefan Batory (1533-1586), one of the most famous rulers of Poland during her ‘Golden Era,’ was Hungarian.

This connection between the Poles and Hungarians was not lost on our guide in Budapest, who repeated the famous words Lengyel, magyar — két jó barát,. együtt harcol s issza borát, “The Pole and Hungarian are two good friends. They fight and drink together.” As dusk slowly began to fall upon Heroes’ Square, he pointed out the statue of Ferenc II Rákóczi, who had been the first to lead a major uprising against Habsburg rule in 1703-1711, and who, coincidently, had also been nominated twice to the kingship of Poland after having fled there once the Austrians had quelled the rebellion. This story, of course, reminded me of the most famous Polish king of Hungarian origin, Stefan Batory, who had presided over Poland during her Golden Era, won many victories over the Russians, and is fondly remembered in many chronicles of the time.

Ferenc Rákóczi (1676-1735) fled to Poland after his failed uprising against the Austrians. He was later nominated for the kingship of Poland.

Our guide spent twenty minutes explaining that statue of Ferenc II Rákóczi, and as it became clear that there would not be enough time to explain each of the fourteen statues on Heroes’ Square, we boarded the metro for the Buda side of the Danube. The famous Castle Hill, or Várhegy, like the histories of Hungary and Poland, is deeply layered, and although the present-day edifice of the castle reflects the baroque architecture of the Hapsburg Empire, beneath the castle dome one can find the remnants of walls that stood against Turkish sieges and perhaps even the remains of Matthias Corvinus’ library, which had been ransacked and its contents dispersed by the Turks following a siege in 1490. The Poles had also fought some of their most famous battles against the Turks, and it was not a surprise to learn that Poles fought alongside the Hungarians at the Battle of Mohács in 1526, after which the Hungarians lost their independence to the Ottoman Empire. About three thousand Polish knights perished fighting the Turks at Mohacs, along with 18,000 Hungarians.

Statue of Józef Bem, Budapest

We emerged along the Danube embankment across from Budapest’s brightly lit parliament building, a stone’s throw from the castle and near several monuments commemorating important events in Hungarian history, including the aforementioned statue of Józef Bem, which, crowned in wreathes and ribbons, reads ‘Let this statue stand as a symbol for Hungarian freedom.’ Monuments and symbolic commemoration play an important role in strengthening Poland and Hungary’s historic ties. The statue of two oak trees commemorating Polish-Hungarian friendship in the Hungarian city of Győr was unveiled in 2006 by Hungarian president László Sólyom and the late Polish president Lech Kaczyński. The symbol of the oak tree alludes to a poem written by the Pole, Stanisław Worcell, in the nineteenth century:

‘The Pole and the Hungarian are like two eternal oaks, each of which grew into a separate trunk, yet whose roots extend deeply under the ground and have bound up and fused in ways invisible. The wellbeing and vigor of one is the condition of life and health of the other.”

Perhaps it is the mutual trust, reciprocal aid, and support between two nations sharing a very similar fate and historical destiny that has led to the allusion of two eternally intertwined oak trees. During the time that Worcell wrote his poem, after all, three thousand Polish legionnaires fought alongside the Hungarians against the occupying Hapsburgs, including commanders Józef Bem, Henryk Dembiński, and Mieczysław Woroniecki, the latter who was killed in battle and commemorated as a martyr for Hungarian independence.

Later, during the Poles own battle to secure an independent Poland against the invading Bolsheviks following the end of World War One, the Hungarian government of Pál Teleki transported over one hundred million rounds of ammunition to Poland, free of charge, to assist the embattled Poles. Teleki, in fact, had wanted to send up to 30,000 troops to bolster the Polish forces, but was prevented from doing so due to the pernicious situation on the border at the time with neighbouring countries.

On March 12, 2007, the Hungarian government declared that the March 23 would be recognized as the Polish-Hungarian Day of Friendship. This day is commemorated in many ways throughout Poland and Hungary, with concerts, festivals, and exhibitions. The 2011 anniversary of the Polish-Hungarian Day of Friendship in Poznań was celebrated by Polish President Bronisław Komorowski and Hungarian President Pál Schmitt and attended by over five hundred people. Komorowski remarked that, “there are few cases in history where there exists such a long and peaceful co-existence between two nations,” while Schmitt, in turn, declared that “the Polish-Hungarian friendship is eternal.”

On March 12, 2007, the Hungarian government declared that the March 23 would be recognized as the Polish-Hungarian Day of Friendship. This day is commemorated in many ways throughout Poland and Hungary, with concerts, festivals, and exhibitions. The 2011 anniversary of the Polish-Hungarian Day of Friendship in Poznań was celebrated by Polish President Bronisław Komorowski and Hungarian President Pál Schmitt and attended by over five hundred people. Komorowski remarked that, “there are few cases in history where there exists such a long and peaceful co-existence between two nations,” while Schmitt, in turn, declared that “the Polish-Hungarian friendship is eternal.”

View of the Castle Hill (Várhegy) in Budapest.

Standing atop the Castle Hill of Budapest, and gazing out upon the historical and cultural legacy of Hungary, a product of the past one thousand years of history, one can gain an appreciation for the tenacity and wherewithal of those first, intrepid groups of Magyars who settled among the Slavs of East-Central Europe. And among those Slavs, it was the Poles, a nation likewise forged in the furnace of conflict, that extended the hand of friendship to a fellow nation embattled in seeking to maintain its autonomy and freedom from foreign domination. Let us hope that Polish-Hungarian Friendship lives on for another thousand years.

CR

I am glad you enjoyed your visit to Budapest and I appreciate your interest in the history of Hungary. Born and educated there, I know about the traditional friendship between Hungary and Poland that you referred to in your article. I left the country after the failure of the 1956 revolution against a terror-driven dictatorship, and resettled in California. In 2012 I spent a week in Poland, visiting Warsaw, Krakow, Zakopane, and Auschwitz,learning more about the country’s history along the way. The suffering Poland endured in WWII was far beyond what we experienced in Hungary,though it was bad enough. Sadly, as teaching of history in schools is being downgraded in importance today, those times and events are slowly fading from memory. I tried to delay that process by writing a book, Degrees of Courage, in 2012, shining a bit of light on Hungary’s 20th century history as a framework for the story of my family. There are some excerpts on my website, and reviews at Amazon, and if you find them interesting, I’d be glad to send you an electronic copy. Just let me know via e-mail to grety10@aol.com

Thanks again for your article,

Shari Vester

1000 lat;-)