PHOTO of Stuart Dybek

courtesy of the John D. & Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation

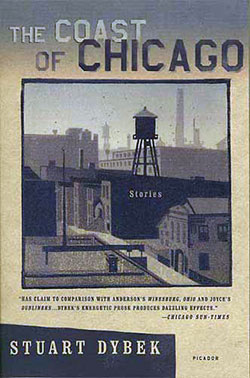

Acclaimed American writer Stuart Dybek is an exception among writers of modern fiction: he has built his reputation largely on the strength of his short stories. Dybek is known for two collections of poetry, Brass Knuckles and Streets in their Own Ink, and three works of fiction, Childhood and Other Neighborhoods, The Coast of Chicago, I Sailed with Magellan. In June 2014, Farrar, Straus & Giroux published two new books by Dybek: Paper Lantern: Love Stories and Ecstatic Cahoots. Through the years, he has received much recognition for his work, including a MacArthur Fellowship (also known as a “Genius Grant”), a Guggenheim Fellowship, a Rea Award for the Short Story, and a Lannan Literary Award for Fiction. His work has appeared in many magazines, including The New Yorker, The Atlantic Monthly, The Paris Review, and Harper’s Magazine.

A girl and her old beach umbrella, a grandfather soaking his feet and drumming his fingers on the kitchen table as if it were a piano, a condemned man moments before his execution, and a young man who likes to watch Pet milk swirl in his coffee, these are some of the characters that populate Stuart Dybek’s fiction. They linger on the past. They feed on dreams. In Dybek’s fiction, to quote from his story “Paper Lantern,” “the present turns ghostly with memory and yet resists quite becoming the past.”

Chicago’s Polish section on Milwaukee Ave.

PHOTO: Wuhazet-Henryk Żychowski

Most of his stories are set in the Pilsen and Little Village neighbourhoods of Chicago, where the writer grew up among immigrants from eastern Europe and Mexico. The action takes place in apartment buildings, stairways, alleys, taverns, and by the railroad tracks. A seasoned fabulist, Dybek is able to transform an ordinary working class Chicago neighborhood into something extraordinary.

Many of his stories avoid linearity, and the reader enters them as if they were an unknown city with winding streets, not knowing what may be hiding behind each corner. The realistically described settings are often imbued with the fantastical, whether it is a reflection of a ghostly woman from the past in a mirror, a miniature bride and groom in the fridge, scientists building a time machine, or a lifeguard possibly saved by a dolphin.

Dybek is also a poet, and it should be no surprise that lyrical moments are frequently interwoven into his narratives; these bring back to life a world long gone, one in which the silhouettes of people who are no longer part of the present moment linger on. Even the trains can be magical in the literary world he creates, like the one in his story “The Caller.” He writes: “Wait alone on the L platform for an empty night train, the kind of train that clatters through the sleep, a train boarded by nightmares and dreams masked like luchadores, indistinguishable from one another in their babushkas, fedoras, respirators, and dark glasses. When it reaches the end of the line it won’t stop.” The cityscapes that Dybek constructs are inspired by the American neighbourhood where he grew up, yet they also conjure the landscapes of the Old World, which one sees depicted in twentieth-century European literature or the magical universe found in the novels of Gabriel García Márquez.

A second-generation Polish American, Dybek was born on April 10, 1942 in Chicago. His father, Stanley, immigrated to the United States from Poland as a young child. His mother, Adeline, née Sala, was born in the United States but also came from a family of Polish immigrants. As a child, Dybek loved books, often reading at night with a flashlight in hand, and he loved collecting butterflies. He was an unruly child and student. His father even nicknamed him “Weed.” The oldest of three brothers, Dybek was the first in his family to attend college. When he began his studies at Loyola University in Chicago, he hoped to study pre-med and become a doctor, but soon changed his mind and majored in English instead. After graduation, he taught in public schools in the Caribbean and, after his return to the States, he decided to pursue a PhD in education at the University of Iowa, and dreamt of starting his own school in inner-city Chicago. However, he was also admitted into a creative writing program, which he ended up pursuing, and he received an MFA from the famed Iowa Writers Workshop, where he studied both poetry and fiction. He retained his commitment to education and he has been a very dedicated creative writing teacher. For many years he taught at Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo. Since 2006, he has been a Distinguished Writer in Residence at Northwestern University, where he teaches his students not merely to write what they know but to explore the realm of the imagination.

Music powers Dybek’s imagination and it plays an important role in his stories. He listens to it while he writes. In a way, music becomes something like a magic lantern that projects images onto his imagination that he, in turn, puts onto paper. An organic part of his writing process, it also finds its way into his fiction, whether it is a car radio playing jazz, a girl playing Chopin, or Pavarotti singing Turandot. Dybek’s stories are brimming with sounds. His narratives contain visual, auditory and olfactory details. There is a scent of a woman and of winter, smells of roasted chestnuts, cabbage, garlic, smells of milkweed, horses, and musty basements, the “smell of trash, oil, and pigeons.” There is the bitter taste of coffee and the ice water that tastes of “rust and moonlight.”

In the midst of his haunting city landscape, Dybek creates powerful characters; in his earlier stories, he has a special predilection for children and elderly people. In “Chopin in Winter,” Dybek paints an unusual bond between Lefty, a boy who struggles with handwriting, and his grandfather, Dzia-Dzia. In the eyes of his family, Dzia-Dzia has failed as a husband and father, just like Lefty is failing most subjects in school. This unlikely duo spends each evening at the kitchen table, the grandson practicing his penmanship, the grandfather reimagining his past, his feet in a bucket of water, as a young girl plays piano in the apartment above. “The silverware would clash and the glasses hum. I could feel it in my teeth and bones as the deep notes rumbled through the ceiling and walls like distant thunder. It wasn’t like listening to music, yet more and more often I would notice Dzia-Dzia close his eyes, a look of concentration pinching his face as his body swayed slightly. I wondered what he was hearing.”

In the midst of his haunting city landscape, Dybek creates powerful characters; in his earlier stories, he has a special predilection for children and elderly people. In “Chopin in Winter,” Dybek paints an unusual bond between Lefty, a boy who struggles with handwriting, and his grandfather, Dzia-Dzia. In the eyes of his family, Dzia-Dzia has failed as a husband and father, just like Lefty is failing most subjects in school. This unlikely duo spends each evening at the kitchen table, the grandson practicing his penmanship, the grandfather reimagining his past, his feet in a bucket of water, as a young girl plays piano in the apartment above. “The silverware would clash and the glasses hum. I could feel it in my teeth and bones as the deep notes rumbled through the ceiling and walls like distant thunder. It wasn’t like listening to music, yet more and more often I would notice Dzia-Dzia close his eyes, a look of concentration pinching his face as his body swayed slightly. I wondered what he was hearing.”

The elderly appear as displaced figures from the Old World who fuel their present life with memories of the past. Dybek seems to be quite fond of them, as they belong to the world of his grandparents. In his poem “Autobiography,” Dybek describes widows “lugging mysterious griefs/by the scruff to novenas.” Later in the same poem he writes: “Any old woman/palsied with love and terror/I called babushka./No word in English turns/a scarf into a grandmother.”

While the old people have memories, children, who have a shortage of memories, instead have imagination and look forward instead of backward. The children that Stuart Dybek depicts in his stories are resilient and creative, but sometimes their dreams are cut short. His story, ”Blue Boy,” included in I Sailed With Magellan, tells the tale of Ralphie, a miracle baby, who survived his life-expectancy and who is looking forward, along with the entire neighborhood, to his First Communion—but he dies before it takes place, on Christmas Eve. Children are asked in school to write compositions dedicated to Ralphie’s memory. Camille, a student who is a talented writer with her novels on the bookshelves of the school library, and who writes the best story about Blue Boy, one day does not return to school and nobody knows what became of her. On the other hand, there are other children, who, like Lefty in “Chopin in Winter,” surpass the expectations that others have of them. Thanks to the music that his neighbour plays and his grandfather’s vivid description of that music, Lefty “had been shaping [his] dreams to it.”

While the old people have memories, children, who have a shortage of memories, instead have imagination and look forward instead of backward. The children that Stuart Dybek depicts in his stories are resilient and creative, but sometimes their dreams are cut short. His story, ”Blue Boy,” included in I Sailed With Magellan, tells the tale of Ralphie, a miracle baby, who survived his life-expectancy and who is looking forward, along with the entire neighborhood, to his First Communion—but he dies before it takes place, on Christmas Eve. Children are asked in school to write compositions dedicated to Ralphie’s memory. Camille, a student who is a talented writer with her novels on the bookshelves of the school library, and who writes the best story about Blue Boy, one day does not return to school and nobody knows what became of her. On the other hand, there are other children, who, like Lefty in “Chopin in Winter,” surpass the expectations that others have of them. Thanks to the music that his neighbour plays and his grandfather’s vivid description of that music, Lefty “had been shaping [his] dreams to it.”

Thanks to music, Lefty improves his writing, as if the sounds that he hears guide his hand and allow him to form perfect letters. Imagination, music, and art constitute a liberating force that allows Dybek’s characters to surpass their humble surroundings and to dream. They educate the young people better than school. Of the orphaned girl in “Oceanic” who loves to draw, Dybek writes: “What she learned […] and then transcribed in her cell was surrender. Her drawings were not about release, they were release—an immersion into an ungovernable invention that swept her beyond anything she might have conceived in school, let alone anything she might have dared to reveal.”

CR

Pingback: Welcome to our 2014 Fall-Winter Issue!