The Piłsudski Institute on Manhattan’s Lower East side intrigued me as a step back into Polish and New York City history. A shabby gray five-story building squeezed between its neighbors on 2nd Avenue, it presented itself to passersby as the Polish National Alliance, at least according to the metal sign above its door. Only those of us in the know buzzed ourselves into the Institute, rushing to pass through two sets of locked doors. Once inside, you found yourself in a five-story walk up that had never quite been converted from a single-family home into apartments. At the top of one flight of wooden stairs, you entered the parlor and the dining room – that is, the Institute office and gallery/reading room. As you sat in the reading room, the floor above occasionally creaked as the librarian hunted down your requests. In the meantime, your gaze drifted over the original Polish paintings gracing the walls (works by Jan Matejko, Aleksander Gierymski, Stanisław Wyspiański, and others) and came to a halt before the huge statue of Marshal Józef Piłsudski himself. His stern look reminded me why I was there.

Entrance to Piłsudski Institute in Greenpoint

I loved working in the Piłsudski Institute at 180 2nd Avenue because of its exceptional collection of materials and hospitable staff. Dr. Iwona Korga, the Executive Director, brought me the huge folders of old newspapers that I’d requested and regularly offered me tea. Dr. Magdalena Kapuścińska, the Institute’s president, sometimes chatted with reading room regulars about our work and treated us to Polish candy in the late afternoon. I appreciated this special place all the more when I realized that it was in danger of vanishing. As Dr. Korga explained to me early in 2014, the Institute’s current lease lasted only to May 2015. The Polish National Alliance, as advertised on its outside door, owned the building and had served as a “good guardian” for the Institute over the last twenty years, in Dr. Korga’s opinion. Yet now the PNA was putting up two of its expensive New York buildings for sale. Old American Polonia was realigning its resources.

An Institute of Last Resort

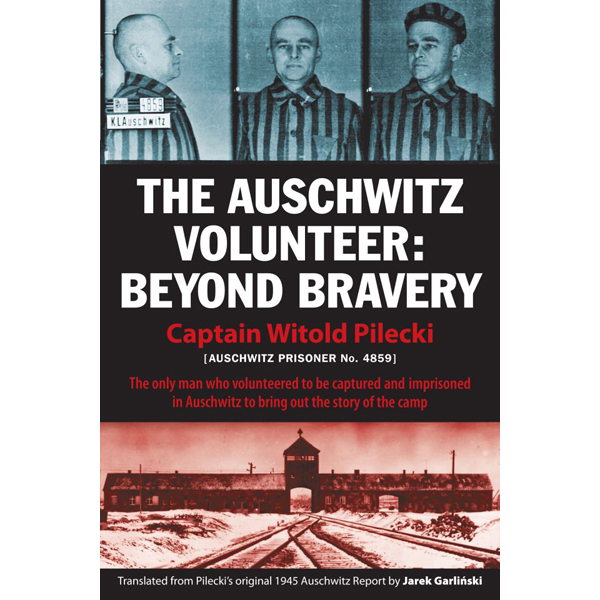

The Piłsudski Institute always had to improvise its existence. It was founded in July 1943, desperate days when recent exiles from Poland were stunned by their nation’s suddenly precarious standing among the Allies. The 1940 Soviet massacre of 22,000 Polish citizens at Katyń, roughly half of Poland’s army officers, had just been discovered by the Nazis. Diplomatic relations between the Polish government-in-exile and the Soviet Union ruptured when the former requested an investigation by the International Red Cross. Both the British and Americans quickly showed their preference for placating the Soviets over demanding justice for the Poles; they needed the Red Army to maintain Europe’s lone front. In the meantime, the Axis occupiers in Poland and elsewhere had shut down all Polish academic institutions and were systematically plundering or destroying collections in Polish museums and libraries.

The Institute was created as an attempt to stop the hemorrhaging of Polish historical documents and to preserve uncensored news of how Polish forces fought and perished in the war. Lacking state support from either Poland or the United States, the Institute relied on its hardworking presidents, pro bono boards of directors, and volunteers to raise funds and gather materials. Over the next seventy years, individual donations and bequests built an impressive repository including over a million documents, a collection of rare wartime and postwar newspapers, a library of over 20,000 volumes, and a gallery of 250 original paintings by Polish masters. Once Poland regained its national independence in 1989, the Institute quickly connected with national libraries and archives, a repatriation that facilitated an important exchange of materials and expertise, with the Institute donating duplicates from its holdings to Polish institutions and professional Polish archivists helping to modernize and digitize its document collections.

What the Institute could not anticipate were patterns of migration in American Polonia and gentrification in New York City. The Polish National Alliance, one of the oldest fraternal organizations in the United States, had streamlined its mission from immigrant activism and education to providing Polish Americans with insurance. The Lower East Side no longer housed thousands of immigrants from Eastern Europe (Jews, Poles, Ukrainians) in overpacked tenements; that past is only on display in the Lower East Side Tenement Museum. Rents on the Lower East Side began skyrocketing in the early 2000s as upscale bars, restaurants, and stores moved in, old tenement buildings were renovated, and new hotels were built. Neither the Alliance nor the Institute could afford to stay put, and no large local Polish community remained to keep them there.

Connecting the Diaspora

New Piłsudski gallery space

To the Institute’s good fortune, another excellent “guardian” materialized in the Polish and Slavic Federal Credit Union, “the largest ethnic credit union” in the United States, according to its website, with over 82,000 members. The PSFCU was founded in 1976 to provide new immigrants the housing loans denied them by other banks; since its establishment in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, the PSFCU has developed fifteen separate branches. It is crucial that a growing Polonian financial institution is supporting the Institute in the next phase of its history. The PSFCU leased the Institute 138 Greenpoint Avenue, a building adjacent to the Credit Union’s historic headquarters. The space at 138 Greenpoint is equivalent in square footage to what the Institute occupied on the Lower East Side. Yet the layout of the new space allows for a grander gallery area on the main floor, directly accessible from the street, and better conservation of the collection, which is housed on the temperature- and humidity-controlled lower level in a modern movable shelving system. Dr. Korga reports that the new Institute “has a very modern look” thanks to architects Wojtek Oktawiec and Beata Buhl-Tatka, who designed the space pro bono to provide maximum light, multifunctionality, and a sleek, space-enhancing color scheme created by special lights, light gray walls, and a dark bamboo floor.

New Piłsudski storage space

That the Piłsudski Institute and the headquarters of its new sponsor are both located in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, marks a new era for American Polonia – an era of transatlantic connection. The northernmost neighborhood of Brooklyn, bounded by the East River, Newtown Creek, and the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, Greenpoint long served as a hub of manufacturing and shipping and home to a large working-class Polish community. Twenty years ago, Greenpoint was known for its gritty waterfront, the stench from the disastrously polluted Newtown Creek (an EPA Superfund site), blocks of vinyl-sided six-family tenement buildings, and the best Polish food in New York. Today, developers, young families, artists, and students fleeing rent-crazy boroughs have brought gradual changes to this low-rise family neighborhood – among them, trendy bars, chic coffeehouses, a few tall buildings, two new parks, and a working farm. While some residents anticipate the sort of gentrification that swept the adjacent neighborhood of Williamsburg, most hope that Greenpoint’s “archipelago of Polishness” will never disappear, even as it shares space with new cultures.

Opening of Piłsudski Institute in Greenpoint

Certainly the newcomers seem as enthusiastic as longtime residents about Greenpoint’s traditional culinary scene – the Polish restaurants, bakeries, and butcher shops that still dot the main arteries of Manhattan and Nassau Avenues. Beyond such ethnic enticements for foodies, cultural entrepreneurs from Poland are invested in engaging Greenpointers, be they Polish or not, in Polish history and culture. About two years ago, Marta Pawłaczek, vice president of the Warsaw-based foundation Culture Shock, launched Greenpoint: The Transition, an ambitious program encompassing historical lectures, cultural workshops, artistic happenings, Polish food tastings, and an oral history project organized in conjunction with the Émigré Museum in Gdynia, Poland. Izabela J. Barry, reference librarian at the Greenpoint Branch of the Brooklyn Public Library, utilizes her public workspace for exhibits of photographs and prints by Polish artists as well as readings and lectures by émigré and visiting Polish writers. Through the combined efforts of Polish Americans and relatively recent immigrants, Greenpoint both imports and exports Polish culture in visual, verbal, and edible form.

Piłsudski Institute “Meet and Greet” with Deputy Brooklyn Borough President Diana Reyna

Now the Piłsudski Institute has added its resources and space to this multilayered relationship between Poland, Polonia, and Greenpoint. Since its opening in July 2015, the Institute has sponsored five documentary screenings, a lecture on the 250th anniversary of the Polish National Theater by journalist Andrzej Józef Dąbrowski, a “Meet and Greet” with Deputy Brooklyn Borough President Diana Reyna, and, most recently, a reception on September 27th for visiting Polish president Andrzej Duda. These events fill the gallery space with visitors; an institution founded as an archive now doubles as a community center. Of course, the Institute as archive continues to attract researchers from all over, serving them better through its much-improved facilities.

Though I’ll miss the dated charm of the Lower East Side location, I’m excited about my first trip to the Piłsudski Institute in Greenpoint. I’ll have to plan my visits carefully, so as not coincide with a dignitary’s visit and not to miss one-of-a-kind screenings, exhibits, or lectures at the Institute or elsewhere in Greenpoint. And now that I know the Institute is located next door to Karczma, one of Greenpoint’s best Polish restaurants, I may have to adjust my research schedule for longer lunches. Culinary studies are essential to good scholarship.

CR

My thanks to Dr. Iwona Korga for her contributions to this article.

Pingback: Welcome to Fall 2015!

Good job, Irena. Can’t wait to visit Brooklyn and Greenpoint. It has been popping up in scenes of New York stories, such as “Bluebloods” a TV drama. The Poles are messy, unruly, and borderline criminals.