In 1943, the Polish government-in-exile sent a delegate to Africa to appraise the situation of the Polish refugees temporarily living in refugee settlements in what was then British East Africa. No doubt this delegate wrote a report but better still, he wrote a book, Gdzie słoń a gdzie Polska, an impressive example of Polish reportage.

In 1943, the Polish government-in-exile sent a delegate to Africa to appraise the situation of the Polish refugees temporarily living in refugee settlements in what was then British East Africa. No doubt this delegate wrote a report but better still, he wrote a book, Gdzie słoń a gdzie Polska, an impressive example of Polish reportage.

The delegate/author, Wacław Korabiewicz, was himself worthy of a book. A medical doctor by profession, he was a man of many talents: an ethnologist, journalist, folklorist, and an adventurer who engaged his keen intellect in his every endeavour. Among his friends he counted Czesław Miłosz who mentioned that Korabiewicz was nicknamed “Kilometre,” because of his height.

I don’t know what was in the report but if it included his understanding of the spirit of the place, then it was a rare government report indeed. For those of us who spent six of more childhood years in the idyllic environment of Polish Africa, the book provides a glimpse into the lives and challenging work of the adults who made our enchanted childhood possible.

Over the years, I interviewed a great many “Polish Africans.” They, of course, recalled their entire experience first of being deported at gunpoint from their homes into the depths of Siberia, and then, after the war, having their dreams shattered, were unable to return home but instead were compelled to forge a new life in a strange new homeland.

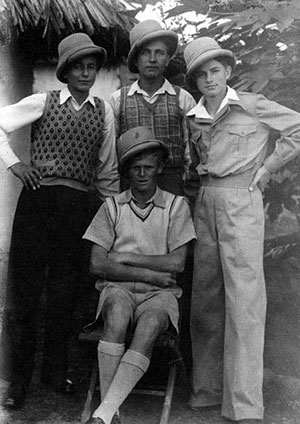

Tengeru teens

This article concentrates on their African years and is a composite of their thoughts and experiences. Their Polish origins comprise a cross-section of pre-war Polish society. Some were children of farmers, both successful and hardscrabble; some were children of professionals, government officials and labourers. By the time I interviewed them, they were all adults, some successful professionals, including doctors and engineers, others worked in sales or other occupations, and many of the women, whatever their education, ultimately gave up their professions to care for families and serve their communities in volunteer work. What follows is an overview of their experiences.

The most important influences were the teachers and guide/scout leaders, in many cases the same people. They restored our childhood to us, made us feel that our lives were important, that we had important things to do in the future.

They were conscious of the fact that terrible things were happening in Poland, that the people were suffering, that children could not go to school, and that the Germans were not only killing Poles but also destroying all elements of Polish culture.

Tenegeru grads

The author’s mother sits in the front row in a dark dress, holding a straw hat

Our education was very important, and in fact it was excellent. It was supposed to prepare us to go home and rebuild Poland, but it turned out to be a good preparation for our lives in Canada. We were never disciplined by force. In fact, we were much loved and indulged. We were motivated to work hard, not forced or punished. Better students coached poorer students.

In the archives at the Sikorski Museum in London, several documents recorded the discussions between the British colonial authorities and the Polish settlement leaders. One point that came up was discipline, i.e. the lack of it so far as the British were concerned. What they meant was corporal punishment for various crimes and misdemeanors of the school children but the Poles replied that corporal punishment for children was against Polish law. I have asked many people about this but to date no one has been able to comment on that. Unfortunately, the war, communism and minority relations have taken up so much research space, I have not found anyone who has studied the laws of inter-war Poland as it related to this issue. That’s a pity. The Polish legal system was quite new, drawn up only after 1920, so it would be interesting to know what it had to say about this and other social issues.

There was no doubt that someday we were going to do important things. Return to Poland and rebuild it. But we were high-spirited. Truancy was common. In fact, the only punishment I remember was in the form of detentions after class but these were usually with a favorite teacher who would take us to sit with him in the shade of a big tree and tell us stories. They were very interesting stories so we enjoyed this punishment very much. There was never any corporal punishment.

When classes went beyond 2:00 pm, we considered this a great injustice, and would try to “escape.” Injustice was a major topic of discussion, both in school and among ourselves. We would “administer” justice to an unjust teacher.

Music in Tengeru

What did they do to deserve punishment?

Mostly skip school. But that was not because we didn’t like school but because of the jungle. Sometimes we just couldn’t resist going there. There was so much freedom and so much to do. We were never bored. We made all our own things. We had Scouts and the YMCA but there was lots of free time for kids to use their own initiative. We formed clubs, meaning kids with similar interests got together. Anything we could find to make carts, or tree houses or forts. Sometimes an old derelict truck would be found for experimenting and kids with mechanical skills could experiment. And those with building skills would build tree houses and forts.

Book clubs, discussion groups, javelin throwing, slingshots, swimming, swinging on lianas, etc. etc. We used a trumpet to call people. You could hear the trumpets all through the camp. Different groups had different tunes so everybody recognized the signals. There was a pretty steady element of mischief, but it was innocent. Africa provided us with a lot of adventure so we weren’t looking for trouble.

We enjoyed studying, we enjoyed playing, we enjoyed everything. We were never bored. The horrors we lived through liberated something in us that was positive.

There was one radio in the camp. We always gathered round for the broadcasts of the news that were transmitted over a loudspeaker. The scouts, that is, the older boys and girls, had the responsibility of taking notes and reading the news to people in the hospital and others who couldn’t get to the radio.

What about the Africans?

There wasn’t much interaction with Africans, or any other groups in Africa. Except with the Scouts. There were a few jamborees where we met African scouts, Hindu and Muslim scouts, and English scouts. We learned a few African words – simba kufa (the lion is dead). We sometimes played football with Africans but that was against the rules. We also met Africans at the missions and got along with them there but otherwise we were aware of their presence but we were apart. Of course we were apart from all groups, we were in the margins, so to speak. We saw the English beat them and they explained to us that one had to beat Africans to make them work. That reminded us of Russia. Apart from that, our African experience was totally non-violent, a complete contrast to our Russian years. Perhaps this helped us overcome our psychological injuries. Hard to say what we thought of it all. We lived in a kind of island of our own.

And yet, said one:

“I learned to be a racist. For no reason other than being white, I could travel in first class on the train while native Africans could not. Years later, I questioned that here in Canada, when I was reminded of that during the civil rights movement in the United States.”

What about the Church? Religion?

Our faith was profound but our religion was emotionally based, ebullient, not at all puritanical or dogmatic. It promoted decency, respect and self-respect.

Was all that happened God’s will?

Not really. Because God does not interfere in the affairs of man. Dopust Boga. We didn’t blame God for the crimes of man. However, we accepted the past without rancour. It transcended our time and place. Others suffered too. We had to accept and forgive in order to face the future. It is up to us how we respond.

Young musicians in Tengeru

This composite reflects the views of many, and though I quote the most articulate respondents, the others expressed similar opinions but less fluently. There was also a contrast between those who had survived the Gulag with their mothers and those who were orphaned, and this brought to mind what the Irish writer, Gregory Maguire, once said: “But I’m really conscious of the fact that I can’t seem to start a novel unless the character doesn’t have a mother. If the mother is still alive, if the mother was there — what’s the problem? There’s nothing to write about.”

And yet, Polish Africa allowed the motherless children to form bonds that were respected, siblings were kept together or reunited if separated at some point during the long trek. Close friendships were important and their value acknowledged by the guardians. But as their care passed from the Polish government-in-exile to the IRO, resettlement was the main concern. At this point, the remaining children faced another traumatic sundering of relationships, the end of their education, and of great hopes for the future. Still, their African years had strengthened them.

One 17-year old, although not of the age of majority herself, persuaded an IRO official that she was the legal guardian of her younger sister. She settled in Canada, worked as a live-in housekeeper, and kept her sister with her. She enrolled her sister in school while taking night courses towards a degree in social work. She eventually became the social services director for a large city hospital. Some had a harder time, but for all of them, this was a very difficult transition. For them, maintaining close contact was an invaluable lifeline. A link to the comforting shade of a Baobab tree.

CR

Pingback: Welcome to our 2014 Fall-Winter Issue!

Pingback: Fall-Winter Version of the Cosmopolitan Evaluate | Posts

Pingback: Chatting with Greg Archer

Pingback: February 1940: Exile, Odyssey, Redemption

My mother Zofia Rarogiewicz is seated 5th from the left next to Mrs Milker on her right in the photo with your mother holding the straw hat. My mother taught handicrafts and was responsible for the sale of the girls’ work to raise money for Tengeru schools. Dr. Korabiewich was a family friend and frequent visitor. I have his book “gdzie slon a gdzie POLSKA”. I was born in Tengeru.