A World Apart

A World Apart

Gustaw Herling-Grudziński

Greatly admired in Europe, and certainly one of Poland’s most important intellectuals of the post-war era, Herling-Grudziński is best known for his powerful, unflinching description of Soviet totalitarianism. His book, A World Apart, was first published in 1951, and it was hailed as a masterpiece by The Observer; praised by Bertrand Russell for its psychological insight into the brutality of the USSR; and in the opinion of the TLS, surpassed Dostoevsky’s House of the Dead. Still, the book did not get much distribution and was not reprinted in English until 1986. In 2005, Penguin Classics released a new edition, this time with an introduction by Anne Applebaum.

That the book was never published in the Soviet bloc, and owning a copy was a punishable crime, is no surprise. That so many Western intellectuals tried to minimize its influence – when not actually suppressing it, as in France and Italy – is a disgrace compounded by their continuing indifference. Very few ever disowned their early infatuation with the murderous regime, the notable exceptions being Arthur Koestler and Nobel Prize winning authors Doris Lessing and Albert Camus.

What was the appeal? One can dismiss out of hand that any of these Leftist intellectuals truly cared about “the workers,” though the notion of being the “revolutionary vanguard,” the anointed leaders of the masses, must have been seductive indeed. Strange that they did not also stumble across Lenin’s other term for them: “useful idiots.”

Still, they were influential. The French publisher, Plon, signed up for it in 1952 and arranged for two chapters in Le Figaro Littéraire but nothing came of it. Camus admired the book and recommended it for Gallimard, but something stopped it there too. The French translation did not appear until 1995 (although the English edition was published in 1985). Herling-Grudziński was interviewed on the popular literary program, Apostrophes, and the host, Bernard Pivot, conceded that the delay was indeed a shame.

In Italy, where the Communist Party was a force to contend with for years, no publisher was willing to risk it until 1994. Discussing the Stalin era was perhaps too embarrassing.

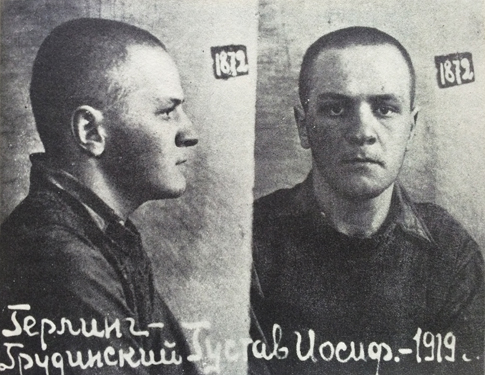

Gustaw Herling-Grudziński. Photo taken in Hrodna’s jail in 1940

A World Apart is the memoir of Labour Inmate No. 1872, Herling’s two years in a Soviet concentration camp on the White Sea. Just 19 years old at the time, he was already a published writer, though his interest was in literary criticism. His experience in the camp, however, gave birth to the writer. A keen observer, he watched and came to the conclusion that conflict, real conflict, is essentially just of one kind: “between the recognition of the essential worth of a man and its cancellation.” He felt compelled to describe it.

It was a world apart, subject to no laws known to civilization. Under the control of psychopaths and ideologues blinded to all reason, they permitted any form of degradation and exploitation of their captive victims. He saw homeless youth, their parents dead or missing somewhere in that vast penal colony that was Russia, encouraged to terrorize the inmates and rewarded for doing so. Hunger, the slowest and most awful death, stalked the prisoners, their bodies reduced to sacks of bones. And he saw committed communists somehow convinced that all this was necessary for the success of the revolution. A gripping, horrifying account of suffering, yet ignored, when not actively denied, by educated people all because of their infatuation with an ideology.

This book is essential reading for anyone who is truly interested in the history of Soviet tyranny, and especially so because of the willful refusal to believe it. The author, moreover was an essential voice for Poland not only for recording his experience in the Gulag, but for his post-war work, especially writing for the Paris-based review, Kultura, established by Jerzy Giedroyc, so that Poles could continue to publish in freedom while their country was under Soviet domination. Kultura proved to be the most influential in formulating free Poland’s democratic course, and in many ways, it still is.

Herling-Grudziński the recipient of the highest awards from his native country, was also honored with the Italian Premio Viareggio prize; the international Prix Gutenberg, and the French Pen-Club.

CR

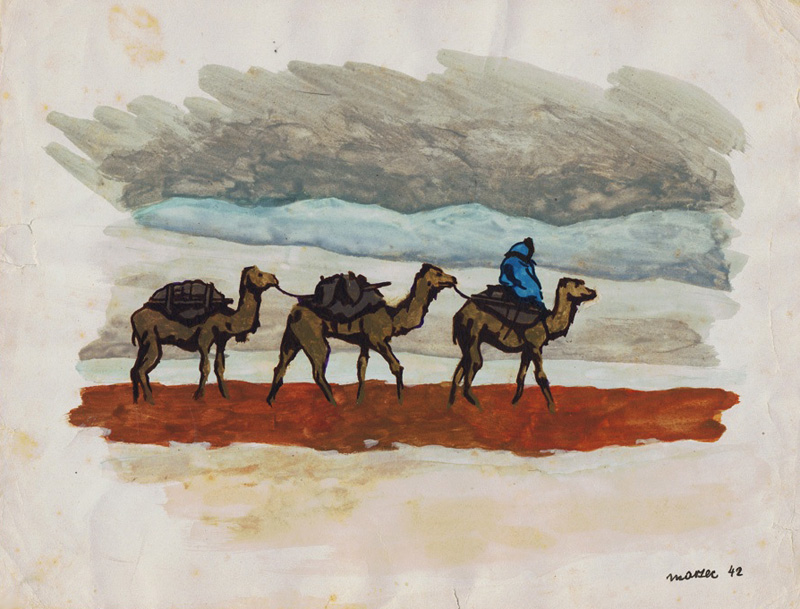

Pingback: February 1940: Exile, Odyssey, Redemption

Pingback: Welcome to our Spring 2015 issue!