Ross Ufberg

While only three percent of books published in the US are translations (only 2.5 in the UK), an astounding 46 percent of books published in Poland are translations. The bigger you are, it seems, the less inclined you are to think there’s anything worthwhile beyond your own borders. Or city limits – if you remember Saul Steinberg’s classic New Yorker March 29, 1976 cover.

With Spain at 24%, Germany at 12% and France at 15%, Poland’s 46% indicates that Polish publishers – and readers – are the least parochial of all. So, a resounding cheer for Poland and now let’s get back to the situation in the US and one independent press that is doing its bit to change that.

We don’t often write about publishers but George Gasyna’s seductive review of Killing the Second Dog – read it and see if you can resist the book – calls for a look at New Vessel Press.

Founded in 2012, NVP already has a catalogue of 18 books in translation, some published others forthcoming: novels from Germany/Austria, Austria/Japan, Moldova, Israel, Italy, Denmark, France, Switzerland, Russia, and even England. England? Yes. Many of the authors are young, several died young, sometimes by suicide.

Four of NVP’s books are from Poland, and Marek Hłasko’s Killing the Second Dog is the second to be reviewed in CR.

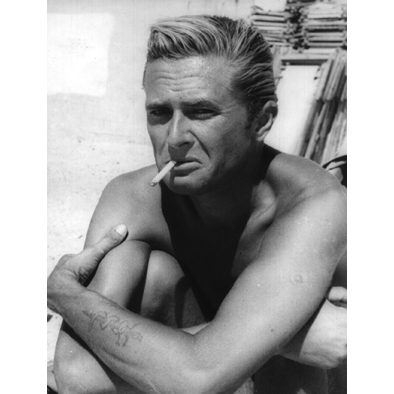

Ross Ufberg, a co-founder of NVP who has written about “the angry young decade: 1955-65” in Poland, the UK, the US and the USSR, seems to have a special understanding of that anger, and sees this anger reappearing in our own troubled times. Hłasko’s life exemplifies that angry decade.

Writing to CR, Ufberg said: “Dostoevsky had Christian love, Hemingway had masculine honor, and Faulkner had the depths of the human heart to combat suffering, but for Polish writer and counterculture icon Marek Hłasko there was only brutal truth, and no clear path to redemption.” He noted comparisons of Hłasko to James Dean’s rebel without a cause but says that Dean’s character did have a cause, while Hłasko was a rebel without a country and came to believe that the world was beyond redemption.

Hłasko’s life, says Ufberg, followed “a tragic arc, and he couldn’t have written it better—or worse. Born in 1934, he was just a boy when the Germans invaded Poland in 1939. He grew up in bleak communist Poland, bouncing his way through a tumultuous adolescence until he discovered writing. His 1956 debut short story collection, First Step in the Clouds, contained stories of doomed love, shell-shocked returning soldiers and drunken boredom. When it won Poland’s most prestigious literary prize, the twenty-two year old was instantly transformed into an icon and a symbol of rebelliousness for his generation. During a brief period of liberalization after the Stalinist era, when the government sent him abroad to publicize the new Polish literature.” Hłasko published two books in France that had been rejected at home. The Polish government summoned him back but Hłasko, after his name was dragged through the mud for being anti-government, asked for a passport extension. “The refusal of this request forced his hand and turned him into an exile.”

In exile, Hłasko gained notoriety. “The New York Times called him a harder, more brutal version of Britain’s Angry Young Men. Hłasko steamrolled across Western Europe, got into bar fights, spent nights in jail and weeks in asylums, worked crummy jobs. A Catholic, he spent a year in Israel living with Jewish friends from the old homeland, during which time he gathered material for four novels. After he put a cigarette out on the cheek of a prostitute who’d insulted him in a bar, he landed in prison and on the front page. When his girlfriend—he was married but estranged from his West German wife at the time—had an abortion without discussing it with him beforehand, he left Israel and went back to wandering.”

Roman Polański, a friend from their early days in Poland, tried to help him but Hłasko could not, or would not, work for someone else. One night he went for a walk with Krzysztof Komeda, writes Ufberg, “the great Polish composer (he’d done the music for Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby). Both of them were drunk. Komeda took a spill, hit his head. A few months later he died as a result of his fall. That was April of ’69. In June of that same year, Hłasko was found dead in his hotel room in Wiesbaden—he was supposed to return to Israel the next day—from an overdose of sleeping pills and alcohol. Was it suicide? Nobody can say. Hłasko left no note.”

The New York Times called one of his novels, All Backs Were Turned “an existential fable,” but Hłasko never intended it as anything other than brutal, realist fiction. He resigned himself to this sort of misinterpretation. “Who was I to demand from people” that they believe in the ugliest things he had witnessed?

“Of course,” continued Ufberg, “in life, as in fiction, victimhood does not an angel make. Consider the following anecdote: In a mental asylum outside Munich where the writer, in order to get away for a while, was sojourning after a fake attempted suicide—Hłasko overdosed on pills, composed a suicide note, and went to sleep in a hotel room, while making sure somebody would discover him before any irreversible damage was done—Hłasko lived next door to a priest. The Nazis had tortured this neighbor so badly he couldn’t comprehend that the war was over and he was no longer a prisoner. “My face reminded him of an SS man he knew,” writes Hłasko, “and he would ask me every morning, ‘Am I going to be executed today?’ I’d answer him soothingly, ‘No need to hurry, Father. We’re busier than hell.’ ”

Hłasko, along with the other writers in NVP’s catalogue, have found a publisher with a passion for thought-provoking fiction. Ufberg, himself a translator, teaches Polish and Russian literature at Columbia. As a publisher, he also brings books across linguistic borders, sharp, stimulating, disturbing works – great 20th century voices – that deserve a large audience.

Check it out at New Vessel Press.

CR

Pingback: Welcome to Summer 2015!