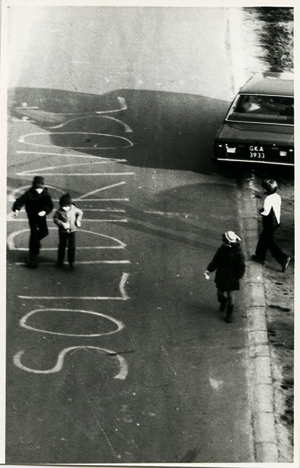

Street protests in Gdańsk-Zaspa,

near Lech Wałęsa’s home, in the 1980s

Photo taken by Jan Neubauer, the author’s father

2014 is a year of many anniversaries that prompt Poles to look back at their country’s turbulent history of the 20th century. In a little over three months, we will commemorate the centenary of the beginning of a world conflict that changed the face of East Central Europe, with sovereignty and statehood for some nine nations, including Poland, which emerged reborn after 123 years of partition, and a new form of oppression following brief independence for others, (inter alia Ukraine). This year Poland will also commemorate the heroic, but tragic, struggle for freedom: the 70th anniversary of the Warsaw Uprising.

After World War Two, from 1947 to 1989 Poland remained a part of the Soviet Bloc, and as such is an important test case of the Soviet Union’s behavior in East Central Europe. Throughout, bilateral relations between Poland and the United States invariably remained a function of Washington’s relations with Moscow. This year, as Poles are getting ready to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the end of communism in Poland, two other major events must be noted: fifteen years of Polish membership in NATO, and ten years since the country became a member of the European Union – both signaling Poland’s new place in international relations. Undoubtedly, it is a good occasion to look back and reflect upon lessons learned.

Street protests in Gdańsk-Zaspa,

near Lech Wałęsa’s home, in the 1980s

Photo taken by Jan Neubauer, the author’s father

Learning to appreciate compromise

What happened in 1989 in Poland is without precedent in the country’s history. Traditionally, compromise has a negative connotation among many Poles. It’s not uncommon to catch the adjective, “rotten,” defining the word “compromise” in the public discourse, while almost unanimously venerated are those who made the ultimate sacrifice in the struggle for freedom – often regardless of the odds. Gloria victis!

Since the fall of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and its subjugation by foreign powers, compromise came to be seen as accommodation, as giving up ideals such as loyalty, patriotism, and honor. In short, as collaboration with the enemy. For a nation of conspirators and insurrectionists, freedom fighters and patriots – as Poles often saw themselves – compromise remained anathema. Even more so during the Second World War and ultimately as Poland fell prey to the USSR due to the West’s accommodation of Stalin’s demands in Teheran, Yalta and Potsdam.

Street protests in Gdańsk-Zaspa,

near Lech Wałęsa’s home, in the 1980s

Photo taken by Jan Neubauer, the author’s father

Yet, in the late 1980s bitter enemies, wedged in the cold war confrontation between two powerful foreign adversaries, sat down to talk and negotiated a compromise that ultimately paved a way to dismantling communism in Poland.

Although some Poles still call it a betrayal, a solution, that provided for gradual transition in the country’s power system, was found in the Spring of 1989. Two months later it proved to be flexible enough to accommodate the will of the people expressed so explicitly in the June elections – the first of any significance since 1947. While the 1947 ballot was a flagrant sham, and the 1989 vote was only partially free, both raised international tensions and marked a change of power in the country.

On June 4, 1989 (and then in the second round of balloting two weeks later) Poles could freely elect the candidates of their choice for their country’s newly reestablished Senate. However, the elections to the lower chamber of the Polish National Assembly – the Sejm – were circumscribed. Based on the Round Table Agreements (Feb. 6 – April 5, 1989), only 161 seats were to be openly contested, the rest (65%) were guaranteed for the Communist Party and its satellites.

Street protests in Gdańsk-Zaspa,

near Lech Wałęsa’s home, in the 1980s

Photo taken by Jan Neubauer, the author’s father

The popular will expressed with the ballot was staggering. The democratic opposition clustered around Solidarity scored a total victory – within the limits of the compromise reached at the Round Table – winning 99 per cent of the seats in the Senate, plus every one of the available seats in the Sejm. However, before the first non-communist prime minister in the Eastern Bloc, Tadeusz Mazowiecki, could be appointed by the President – thus expanding the victory and establishing a historic precedent – the newly reinstated office of the President had to be filled by the country’s National Assembly.

Wojciech Jaruzelski, the general who imposed martial law in 1981, was the only candidate for the post. Riding the rising tide of enthusiasm generated by the June elections, the democratic opposition leaders, who abhorred the idea of electing a communist, were faced with a dilemma: should the Spring compromise be maintained? A surprising endorsement for Jaruzelski came out during a dinner at the American embassy in Warsaw from none other than the U.S. President, George Bush.

Street protests in Gdańsk-Zaspa,

near Lech Wałęsa’s home, in the 1980s

Photo taken by Jan Neubauer, the author’s father

Ronald Reagan’s two-term vice president visited Warsaw shortly before the Polish presidential election in July. If this is not peculiar enough, Jaruzelski’s election also involved an action by some of the democratic opposition leaders who consulted the American ambassador in Warsaw (John Davis) and orchestrated an affirmative but humiliating ballot that left the general without a single vote to spare. This most difficult decision paid off, as the general stepped down a year later opening the way for six candidates, including Lech Wałęsa and Tadeusz Mazowiecki, to compete in the first direct presidential election in Poland, ever.

Third Republic of Poland at 25

Difficult reforms followed the change of 1989. Accepting the compromise, coping with the hardships, and adjusting to the new conditions, the Poles displayed maturity, entrepreneurship, pragmatism and talent. Mindful of the mistakes made along the way, including errors of hastened privatizations, the perils of economic and political crises, attempts to discredit oppositionists who took part in the talks, and resulting cleavages, we now know that the Polish compromise can be ultimately regarded as a success.

Gdańsk, Poland: ul. Pilotów 17,

where Lech Wałęsa lived in the 1980s.

Photo courtesy of the author,

who also lived in this block of flats.

Although, many families in Poland are still struggling to make ends meet, and unemployment still stands at 14% – and this after hundreds of thousands of young Poles had emigrated West in search of better economic opportunities – Poland may still be in its best condition in four centuries! We now live in a country that generations of Poles had dreamt about: free, independent, democratic, with a stabilized economy, people traveling the world both for pleasure and for business: working, researching, studying, publishing across borders, engaged in exchanges in science, business, media, and art. Poles living in Poland and Poles living abroad are openly and mutually proud of each others’ accomplishments.

But a shadow looms over the joyful celebration planned for the 25th anniversary of East Central Europe’s annus mirabilis of 1989. To Poland’s neighbor, Ukraine, thus far this year has been more like an annus horribilis.

A New Cold War?

While the end of 1980s coincided with the collapse of communism in the region, followed by disintegration of the USSR itself, twenty-five years later we find a new Russia rising. Rather than becoming a powerful ally on the volatile international scene and a vital economic partner to the neighboring countries, 21st-century Russia under the leadership of Vladimir V. Putin begins to act like a bully violating territorial integrity of its neighbors (most notably: Georgia, 2008; Ukraine, 2014). Aware of what came before, many countries of East Central Europe anxiously look for support.

One hundred years since the beginning of World War One we ought to engage in a dialog that leads to pragmatic solutions with the potential for improvement and not for appeasement. Ask the peoples of East and Central Europe; they know that the alternative is not an option.

CR

Editor’s Note:

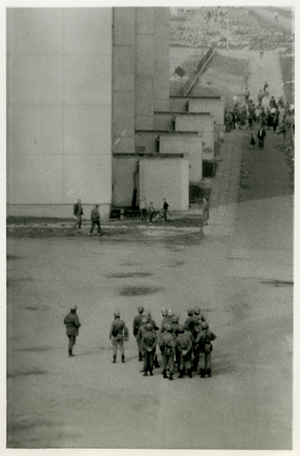

The author of this piece, Anna Mazurkiewicz, shared extraordinary black-and-white photographs taken by her father, Mr. Jan Neubauer, in the 1980s of street protests in Gdańsk – near where they themselves lived, and also near Lech Wałęsa’s home.

She also shared photos that her father took in November 1982, as Wałęsa was returning home from an eleven-month internment. We’ve put them into a photo slideshow below. For a good primer, here’s how the BBC described the day of his release.

Pingback: Welcome to our Winter-Spring 2014 Issue!

Pingback: 1905, A Very Good Year