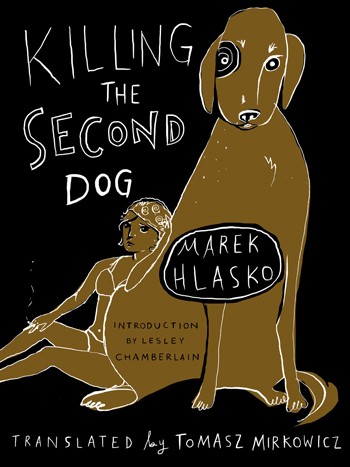

Killing The Second Dog

Marek Hłasko, 1965 (original title: Drugie zabicie psa)

Translated by Tomasz Mirkowicz

Introduction by Lesley Chamberlain

New York: New Vessel Press, 2014. 138 pp. $15.99, Paper

New York’s New Vessel Press has chosen to revive an Eastern European cult classic, the Polish-exiled novelist Marek Hłasko’s 1965 breakthrough Killing The Second Dog, in a brilliant English translation by Tomasz Mirkowicz. Hłasko (Warsaw 1934-Wiesbaden, 1969), dubbed communist Poland’s “bad boy” and one of post-war Eastern Europe’s original Angry Young Men, was a writer who loved to surprise, but here he reaches for territory and a subject position that’s unusual even for him. Killing the Second Dog sees a Polish émigré ex-con and ex-pimp deployed by his partner in crime, a one-time theater director, in tourist season Tel Aviv of the pre-1967 War era (and Zeitgeist), on a “mission” to sadistically swindle and emotionally cripple a would-be paramour. Since book reviewers frequently become, willy-nilly, book recommenders, I should note here at the outset that the requisite plot elements for a noncommittal summery read are seemingly all present and accounted for. Indulge me, then, in a kind of recitation of seasonal hedonism by the seaboard, just like in the old Serge Gainsbourg song: Sea, Sex, and Sun (and repeat until the first winds of autumn start blowing). One could possibly leave it at that, with this type of gloss; however, doing so would do injustice to Hłasko’s novel for two reasons. First, those “elements,” while all present and accounted for, are hardly innocent textual figures or neutral; rather, at least two of them are embodiments of a variously cruel and indifferent nature that plays havoc with people’s dreams and hearts. What is more, they must compete for the reader’ attention with the dictates and demands of the narrator, Jacob’s, achingly overactive memory. The voice that speaks in Hłasko’s texts set in Israel is a subjectivity that seeks to forget his past: the past of the Holocaust in Poland and other local tragedies of the Second World War as inscribed in Polish collective memory. The voice that speaks in this later Hłasko belongs to a character who cannot forget even if he wanted to, especially when in the middle of performing a key scene (indeed it is precisely when he is seeking oblivion – sea, sun, sex – that the images of a personal and collective tragic past keep rushing inopportunely back, flashing back with the power of the returned repressed). Alongside the central idea of summertime forgetfulness, the theme of anamnesis vs. amnesia is one of the two central organizing axes of the novel: it works with – or better, against – the prerogatives of male bravado in the context of a militarized strip of land, bathed in sun throughout the tourist season it is true, but also surrounded by hostile fundamentalist nation-states.

All this apparatus operates in the background, setting up a slow seduction that motivates the plot, orchestrated for money but invoking the West’s highest theatrical authorities in the process of “authorizing” (not exactly the same as legitimizing) an act of fraud. Consider, for example, the following scene:

My real father was a good and gentle man who died when I was six. But a father like that was absolutely worthless, Robert [the theatrical mastermind] said. “Forget him. Your father has to be straight out of Dickens. Maybe even a religious fanatic who drove your mother to an early grave. Leave your parents to me.” I soon learned that … I did not have a father at all but was the illegitimate son of a washerwoman who knew nothing at all about my father except that he was a corporal on summer maneuvers with his regiment. “The unfortunate child grew up like a weed and a sore in everybody’s eye,” Robert told the poor bitch [the target of their swindle], pointing at me. Both of them had tears in their eyes. [58]

At certain times during the performance, especially as he enacts its most cynical, emotionally devastating – and for that reason, all the more affective – scenes, Jacob gets stuck or falls out of character. Inadvertently, and also despite his better judgment, Jacob who, as we learn, by this point has several such performances under his belt, falls in love with Mary, the 40-something Jewish-American divorcee, whose own sojourn to Israel constitutes a hopeful exercise in forgetting. He feels obliged, however, to remain faithful to the compact he entered into with Robert, the cynical “director” wedded to his craft only, and carry out the seduction to its inevitable unhappy end (a note to the gentle reader: seduction in modern Polish literature frequently terminates in catastrophe, the more elaborate the scheme the more tragic the outcome; cf. Witold Gombrowicz’s – contemporaneous – Pornografia or Kosmos; anything by Witkacy. Hłasko simply seems to mobilize this formula in a theatricalized fashion in an exotic locale. The conclusion is foregone, however).

As Lesley Chamberlain’s Introduction – definitely required reading, its few factual errors notwithstanding – nicely elucidates, Hłasko found himself in Israel in 1959 almost as an accident of fate. Socialist Poland’s favorite (faux-) proletarian author (for Hłasko’s father had been a prominent attorney and legal expert in Warsaw before the outbreak of the Second World War) Hłasko was effectively banished from Poland following a 1958 regime purge – and specifically as a consequence of a few interviews he gave while on fellowship in Paris in 1958. These contained exposés of life in socialist Poland that the regime in Warsaw could not countenance. Once on the road, where so many of the characters of his fictions would find themselves, Hłasko probably expected the Israel episode to count as a brief and pleasant interlude. We know from surviving correspondence with family members and friends that it proved to be an extremely trying period, forcing Hłasko – for survival’s sake – to fall back on the one role he knew how to play adeptly and which had served him well in the Poland of his youth: that of the obstreperous performer of the theater of public life, the truculent prodigy, the rebel without a cause willing to rack up nights in jail or the “sobering room” as he “charmed” (or failed to charm) local authorities and experts. In fact, in Israel, he ran afoul of the authorities more than once – the conceit that Robert and Jacob should meet during a stint in jail and concoct their scheme as each awaited sentencing for various petty offences is semi-autobiographical – but it appears that near everyone had a soft spot (or a reservoir of patience) for the bad boy. He remained in Israel until late 1960, and the long sojourn provided him with material for his most mature and best work, the so-called Israeli Tales, a cycle of three novels and a half-dozen short stories. It’s heady stuff, even today, and assembles a constellation of elements that critics of the earliest English translations rightly saw as nearly unprecedented in European fiction of the time. Raw, hard hitting prose from the template of the American detective tale genre/pulp fiction enriched with bombastic dialogues seemingly culled from big-ticket Hollywood romances commingle here with something more durable though still impressionistic: starkly existentialist memory work of a survivor with too many stories to tell, with an excess of memory – a burden of which he needs to be divested somehow. These two prerogatives fight to a draw in the narrative, almost: for what it’s worth, in the experience of this reader, the tragic wartime recollections have proven far more resilient. I first read Killing the Second Dog over two decades ago, and the images of WWII and the Holocaust Hłasko had irradiated linger still, while the witty repartee of the protagonists has faded to the background though still can produce a chuckle on a second rereading and even a third. They are nearly as sharp as I remembered them from the first reading, but these days they also feel more frozen in place – calcified symbols of another place and time, a profane passion play, the braggadocio of unknowing losers of history. The memory work Hłasko had embarked on for this text, on the other hand, has culminated in something far more lasting, something along the lines of a sacred image… Sacred paradoxically because the lives depicted in the narrator’s flashbacks – the lives and particularly the deaths – were so utterly disposable to the Nazi overlords (and the Soviets who subsequently came to liberate/enslave).

As I mentioned, the narrator suffers from a surfeit of memory; his mind is filled to bursting with it; he feels it is his task to share it – even with the person he will ultimately injure profoundly (whose heart he must break), the one person who should not be allowed to peer under the mask, if the con game is to be a success.

It would have been a relief to tell her everything… and I wouldn’t have needed Robert and his goddamn instructions to do it either. It would have been a relief to tell her about the Jewish family hiding next door until they were murdered by the Germans. A man, a woman, and three children… and it would have been a relief to tell her how one day when I was walking to school, the Germans blocked off the street and made us watch them hang people from balconies; no one moved or screamed, not those forced to watch, nor those who were being hung… but I didn’t say these things. I lay next to her and the warmth of her body enveloped me and put me to sleep, and there was nothing else I wanted to feel or think about. [108-9]

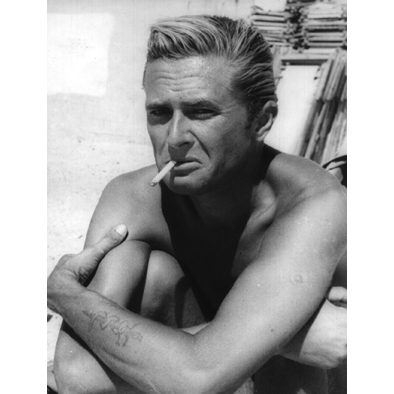

Marek Hłasko aka the Polish James Dean

One feels glad, then, that the real Hłasko found it within himself to commit this to paper.

The edition is produced on high quality paper, and the text itself very readable in low contrast settings (essential while at the seaside, under the sizzling sun…). In his justly admired translation Mirkowicz did very well to balance the clipped, staccato, streetwise – very often smartass – dialogues between Jacob and his “director” with more nuanced, nostalgic introspective passages that speak of an agonized longing for a lost Poland and for the possibility of durable love, as well as the aforementioned, brutally direct, wartime flashback scenes. By all means, bring a copy to the beach with you this summer. But perhaps best leave your dog at home.

CR

Pingback: Russ Ufberg and New Vessel Press

Pingback: Welcome to Summer 2015!