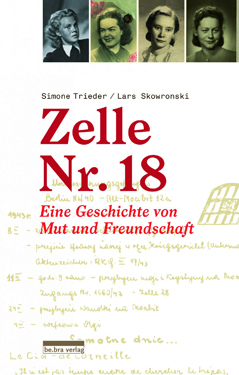

On June 26, 2014, there will be an unveiling of a monument in memory of a young and rather unimportant member of the Polish resistance, Krystyna Wituska, in a cemetery in Halle-Saale, a city in the German state of Saxony-Anhalt where prisoners from the Alt-Moabit prison in Berlin were taken for execution, by guillotine. There is a museum there as well as a memorial centre dedicated to all the victims killed there, many of them Germans, but Wituska was chosen as the figure who will represent them all. The funding for the monument was initiated by the daughter of the judge who sentenced Wituska to death. The 26th marks the 70th anniversary of her execution; also on this date German authors, Simone Trieder and Lars Skowronski, will launch their new book about Wituska and her Polish friends who shared Cell No. 18.

On June 26, 2014, there will be an unveiling of a monument in memory of a young and rather unimportant member of the Polish resistance, Krystyna Wituska, in a cemetery in Halle-Saale, a city in the German state of Saxony-Anhalt where prisoners from the Alt-Moabit prison in Berlin were taken for execution, by guillotine. There is a museum there as well as a memorial centre dedicated to all the victims killed there, many of them Germans, but Wituska was chosen as the figure who will represent them all. The funding for the monument was initiated by the daughter of the judge who sentenced Wituska to death. The 26th marks the 70th anniversary of her execution; also on this date German authors, Simone Trieder and Lars Skowronski, will launch their new book about Wituska and her Polish friends who shared Cell No. 18.

Wituska’s nephew, Tomasz Steppa, has been invited to attend the ceremony. He has promised to send photographs and further details about the ceremony and we, at CR, will share them with our readers on our facebook page.

Krystyna Wituska is almost unknown so this unusual event – a memorial to a Polish heroine – is no doubt surprising. She is not unknown to us at CR, however, so we share this background.

Wituska, born May 12, 1920, was from Jeżew, where she lived on a large sugar beet plantation owned by her father. Educated at home by governesses, her studies emphasized languages, history and culture. For her final years of high school she was sent to a convent school in Poznań and then went to a finishing school in Switzerland. This was just after her engagement to a young man from the family’s circle of friends, though it was agreed that they would finish their education before marrying.

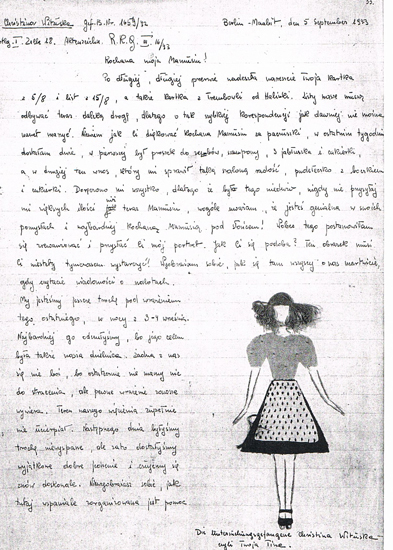

Krystyna’s letter to her mother, illustrated with a “self-portrait”

In the summer of 1939 Krystyna was already in Switzerland when the world began to feel the winds of war spreading from Germany. Her fiancé was already mobilized but the strong-willed Krystyna insisted on coming home so that the family could be together at such a difficult time. Reluctantly, her parents agreed; nobody at that time could imagine the barbarism that was to come.

And come it did, swiftly and brutally. The Wituskis, their home in western Poland quickly overrun by the German army, were summarily evicted and forced to leave with only what they could carry to central Poland, the area the occupying Germans called the Generalgouvernment, (the word “Poland” was banned.) The Wituskis found shelter wherever they could, at first inside churches and barns but eventually they shared rooms with relatives in Warsaw. It was there that Krystyna gradually drifted into the resistance.

The windows of Alt-Moabit prison

PHOTO: Daniel Reinhardt

She was arrested in 1942, interrogated at the infamous interrogation centre, Aleja Szucha, confined for a while at Pawiak Prison, and then sent to Berlin to be tried by a military court. It was in Berlin, at the Alt-Moabit prison that Krystna Wituska wrote over 80 letters, one of the most remarkable prison correspondences not only because of her literary flair but also because many of the letters were written to a German “pen-pal,” the daughter of a prison guard who did everything in her power to ease the suffering of Krystyna and her Polish friends. The affection was mutual; the Polish prisoners called the guard, Helga Grimpe, Sonneschein (Sunshine) and her daughter “Teddy.” Mrs. Grimpe smuggled these letters as well as letters the Polish women wrote to their parents so that they could bypass the censors. After the war, she delivered all of Krystyna’s letters to her parents. “Teddy” had collected them in an album called Kleeblattalbum, kleeblatt being the German word for clover. Krystyna signed many of her letters with a cloverleaf, each of the three petals representing the three cellmates, Krystyna, Monika and Lena.

The first page of Teddy’s Kleeblattalbum with Krystyna Wituska’s image set into a cross and a dedication in German beneath:

Lived as a human being

Ennobled to the status of heroine

Through bitter suffering

Ended as a holy person

For the freedom of Poland

The letters reveal a spirited, well educated young woman of philosophical bent, a gifted writer, warm, affectionate, often funny though at times expressing rather dark humour, brave and kind, concerned more often about others – especially the anguish of her parents – than about herself. While she never abandoned hope, she was a realist and well aware of the horrors of this particular war.

And this brings us to the event coming up June 26, a monument in Germany honoring someone almost unknown, though her prison correspondence had attracted a little attention in the past.

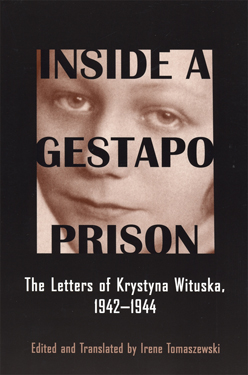

The first reading of Wituska’s letters, in English, was in a Canadian documentary made in 1994 for the CBC, A Web of War, in which Canadian actress Tamara Górska read some passages. CR editor, Irene Tomaszewski, was then working as a researcher and associate producer on this film and it was she who obtained and translated these letters. Encouraged by the film crew, she translated all of them and they were first published in a Canadian edition under the title, I Am First a Human Being: the Prison Letters of Krystyna Wituska (now out of print). In 2006, Wayne State University Press published an American edition under the title Inside a Gestapo Prison: the Letters of Krystyna Wituska.

The first reading of Wituska’s letters, in English, was in a Canadian documentary made in 1994 for the CBC, A Web of War, in which Canadian actress Tamara Górska read some passages. CR editor, Irene Tomaszewski, was then working as a researcher and associate producer on this film and it was she who obtained and translated these letters. Encouraged by the film crew, she translated all of them and they were first published in a Canadian edition under the title, I Am First a Human Being: the Prison Letters of Krystyna Wituska (now out of print). In 2006, Wayne State University Press published an American edition under the title Inside a Gestapo Prison: the Letters of Krystyna Wituska.

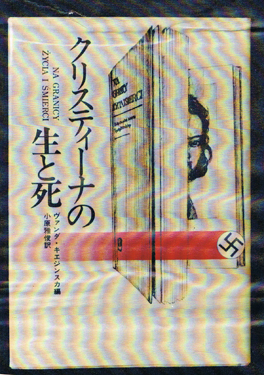

A now out-of-print Japanese edition

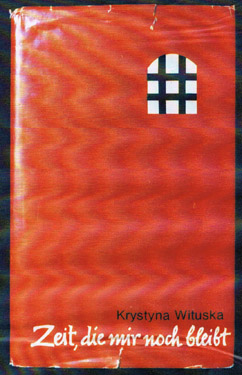

In the course of researching Krystyna’s story, Tomaszewski discovered that there had been a Japanese edition and two earlier German editions, though all presumably long out of print.

CBC radio has aired a dramatic reading of the letters, and once featured Wituska’s story in a Remembrance Day program; dramatic monologues have been presented at numerous schools, libraries, and community centers in Montreal, Toronto and Vancouver. Most recently, Emory University student, Natalya Zmudzin, performed a superb one-woman play at Luzerne College in Shamokin, Pennsylvania.

Those of us who have an interest in Polish history have noted that historians like to point out that Poles glorify their heroes. To excess. Most people accept that as a valid criticism but if that’s the case, it raises an interesting question. Why, then, are Polish heroes largely unknown? Seems like a contradiction.

It took 50 years for the first English language book about Żegota to be published; the marvelous Irena Sendler, who was a member of Żegota, only achieved fame on her own in the last decade or so and most of her Żegota colleagues are still unknown; Pilecki remained in obscurity until Aquila Polonica published Pilecki’s memoir two years ago. How many people know about Władysław Bartoszewski? And there are so many others. It seems Polish historians find it unseemly to mention Polish heroes, probably because of the criticism mentioned above. While it’s true that Poland produced a lot of heroes, it’s really through no fault of its own. All of these girls and boys, women and men, would have preferred to just continue their lives as students, lawyers, doctors, engineers, artists, farmers, teachers, and so on – if only they’d been left in peace to do so. But really, there’s very little evidence that too much is written about them; quite the contrary, they’ve gone down in obscurity. Avoid the word “hero” if that is bothersome. But don’t avoid the people.

A now out-of-print German edition

So it is with heartfelt thanks that we greet the news that Krystyna Wituska will be honored in Germany. We hope this generates renewed interest in her and the book with her letters. They provide a rare glimpse of a Gestapo prison, an inspiring story of young women with an indomitable spirit, and much to think about. World leaders seem to be strangely obliging to men of dictatorial bent, the business of selling warships and attack helicopters being more profitable than human rights. They forget that it is ultimately ordinary people who pay the price. The young Krystyna has much to teach them:

“I did not become a nationalist here, quite the contrary. I consider strong nationalism to be a serious limitation and I always consider myself first a human being and only then a Pole. On the day that I will die I would prefer to tell myself that I am dying for freedom and justice, rather than just for my own Poland. Consciousness of a universal humanity will comfort me. But please don’t misunderstand – it is not that I don’t love my own country but I would relinquish my country’s objectives if they were not also good for all of Europe and all of humanity.”

These words should be essential reading for Europe’s leaders.

CR

Pingback: Welcome to our Summer 2014 issue!

Would like to subscribe to Cosmopolitan Review. Please provide information.

We’re delighted you’d like to subscribe! Our subscribe button is at the bottom right of every page, including the home page: http://cosmopolitanreview.com/

Hello, following my great interest in the Letters of Krystyna Wituska (edited by Irene Tomaszewski), I would like to be able to contact Ms. Tomaszewski personnally,as it is about a project concerned by these Letters. Could you please give me her email address (or tel etc), thank you in advance, cordially, Marine

Pingback: 2014: The Year of Anniversaries

i saw my fathers name on pawiak prison transport lists it was zbigniew lewandowski born 1.3 1926. what a terrible prison. wayne lean