Union of Lublin; Jan Matejko painting

Perhaps the most appealing elements of the Polish heritage can be traced to the sixteenth century when the Rzeczpospolita, that is the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, came into existence as a result of the Union of Lublin on July 1, 1569. It is one of the very few examples in European history of a successful multi-national federation in which diverse peoples, ethnically and religiously (Poles, Lithuanians and Ruthenians) freely joined together to create a political union which provided autonomy, security from external dangers and religious toleration. Even today it can serve as a useful model for the European Union. In contrast to Western European countries of the sixteenth century with absolutist divine right monarchies, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth had a limited monarchy with legislative supremacy of the nobility recognized and the principles of consent of the governed and social contract affirmed. These are the very principles that are associated with modern democracies today. The Rzeczpospolita was spared the religious wars that plagued the rest of Europe since its sovereign, King Sigismund August II refused to be drawn into religious quarrels and declared, “I am King of the people, not of their consciences”. So with its hallmarks of compromise, toleration, local autonomy, and cultural pluralism, this Commonwealth-Republic endured for two centuries without internal disruption and was able to survive and even grow stronger in spite of the “deluge” (potop) of the seventeenth century caused by the Swedish, Muscovite Russian and Turkish invasions.

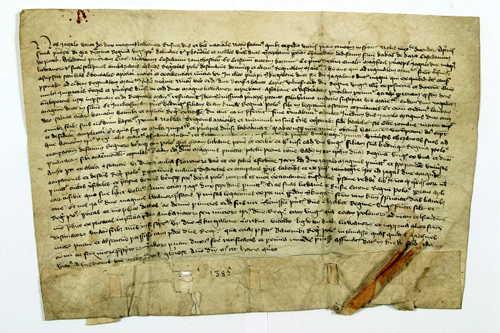

Treaty of Krewo

But the Union could not have been consummated had it not been prepared by a long, nearly 200-year evolution that began in 1385 with the Treaty of Krewo intended to deal with a common threat from the Teutonic Order. The treaty arranged the marriage between the very young Jadwiga, crowned King of Poland in 1384, and Jagiello (Jogailla) Grand Duke of Lithuania, after the latter promised to unite his Lithuanian and Ruthenian lands to the Crown of Poland and convert his dynasty and his nation (the last ‘pagan’ people of Europe) to Catholicism. The co-Kings of Poland, Jadwiga and Jagiello initiated a profound cultural transformation under Polish influence in the Grand Duchy with its attractive dimension of freedom and liberty slowly replacing the more absolutist system dominated by Lithuanian magnates. In 1387 Catholicism was officially introduced into Lithuania with the founding of the first bishopric in Vilnius (Wilno). It received all the privileges equivalent to the Church in Poland and at the same time the first charter of privileges was granted to the Lithuanian boyars (gentry) similar to those enjoyed by the Polish nobility (szlachta). Following the spectacular joint Polish-Lithuanian victory over the Teutonic Knights at the Battle of Grunwald in 1410, the Horodło agreement of 1413 further strengthened the dynastic ties. But more important than the legal settlement was the gesture of solidarity and brotherhood by forty-seven Polish noble families who adopted the same number of boyar families in Lithuania granting them the right to bear their coat of arms.

1387: Poland + Lithuania

GRAPHIC by M.K.

After some ups and downs, the remarkable merger of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania into one indivisible common Republic–Commonwealth (Rzeczpospolita) was finally agreed upon, freely, without force, on July 1, 1569 in Lublin. It was made possible by the wise leadership of King Sigismund August II, the last of the Jagiellonian dynasty. The Union of Lublin provided for a single elected sovereign (King) and a single consolidated Sejm (Diet) but it was not a unitary state but instead a federation. The Grand Duchy of Lithuania maintained a separate identity with its own administration, treasury, army and law. Thus this new union was assured permanence for the future by stressing equality and respect for distinct traditions and customs, even though the Poles were obviously the stronger senior partner. A portion of the territory of the Grand Duchy that included Podlasie and Volhynia with the vast regions of Kiev and Bracław (present day Ukraine ) were incorporated directly into the Kingdom of Poland. This placed a greater burden on the Polish Crown which now had the major responsibility of defending these territories inhabited by Ruthenians (today’s Ukrainians and Belarusins) from increasing dangers emanating from Muscovite Russia and the Tartars. Indeed, it was the immediate growing threat posed especially by Muscovy’s Ivan the Terrible that helped bring about the historic union in the first place. Interestingly, after a short time a popular slogan among the Ruthenian elite in the new Crownlands of Poland was heard, “Gente Rutheni, natione Poloni” which would be equivalent to Polish Americans declaring today, “I am an American of Polish ancestry.”

The best authority on the Union of Lublin and the events that led to its conclusion, is Oskar Halecki (1891-1973) one of Poland’s greatest historians of the 20th century, who found refuge in America in 1940 following the outbreak of World War II and in 1944 became Professor of Eastern European History at Fordham University in New York. His magnum opus is the two volume Dzieje Unii Jagiellońskiej (History of the Jagiellonian Union) (Kraków: Polska Akademia Umiejętności, 1919) which after almost a hundred years was reprinted in its original form in 2013 by the History Department of the University of Warsaw in its series Klasycy Historiografii Warszawskiej (Warsaw Historiography Classics) under the editorship of Professor Katarzyna Błachowska. It is a testimonial to Oskar Halecki, Professor of Eastern European History at the University of Warsaw from 1919 to 1939 , that the Dzieje Unii Jagiellońskiej is still regarded as a relevant, definitive work about a crucial period in European history. In his posthumous work, Jadwiga of Anjou and the Rise of East Central Europe (ed. Thaddeus V. Gromada) (New York: PIASA Book – Columbia University Press, 1991) Halecki credited Jadwiga (canonized a Saint in 1997 by Pope John Paul II) for paving the way for the Jagiellonian Federal Union of 1569 and making possible the emergence of a distinct region (East Central Europe) roughly between Germany and Russia — sometimes referred to as the “Borderlands of Western Civilization” — no less European than Western Europe, and an integral part of one great Western community of nations. Halecki himself, whose ancestor Dymitr Chalecki-Halecki, the Grand Treasurer of Lithuania was one of the signers of the 1569 Lublin agreement, was a great Polish patriot with mystical feelings for Poland. But he was not a narrow nationalist. He glorified the pluralism of the Jagiellonian Union and brought this ideal to the consciousness of the Polish nation. In the post World War II period he encouraged Europeans including Poles to develop an European supra-national consciousness with the help of federal institutions that would reconcile two great principles, national self-determination and international cooperation. He believed in pluralism with unity. “Whatever is colossal and uniform is definitely un-European” he often insisted. Poles, he contended, should be genuinely concerned for the welfare of her Eastern neighbors, that is Ukraine, Lithuania and Belarus, which were once associated with the Jagiellonian Commonwealth — Rzeczpospolita. Fortunately there is some evidence that present day Poland is pursuing a foreign policy toward its Eastern neighbors consistent with the spirit of the Jagiellonan idea based on respect, equality and freedom of nations. This is an idea that is still very much relevant and vital not only for Eastern Europe but for all of Europe and our Western Civilization particularly in view of current Russian threats to Ukraine and the Baltic states.

CR

Pingback: Welcome to Fall 2015!

I fully agree that the Commonwealth was amazing… but to say “this Commonwealth-Republic endured for two centuries without internal disruption” seems unnecessarily defensive and incomplete.

Among the magnates and szlachta, there was massive internal dissention, exacerbated by the requirement of unanimous consent – and surrounding powers took full advantage of these factors leading up to the Partitions.

Krzysztof Opaliński’s „Nierządem Polska stoi…„ from Satyry(c.1650) is an early comment on point.

As a third generation American who is just starting to research his Polish roots, I have found that my ancestors came from a place called Jalowce. And although Polish was the language my immigrant great-parents spoke, I have recently found that the Jalowce area is where three cultures converged. And that brought me here. This was a very enlightening article.

Great article about a very interesting period of time in Poland and Lithuanian history.

I have also found this article which might be useful for this interesting topic

https://cambridgealert.com/the-deep-history-of-polish-lithuanian-common-wealth/

Pingback: 10 Fun Facts About Poland You Might Not Know About