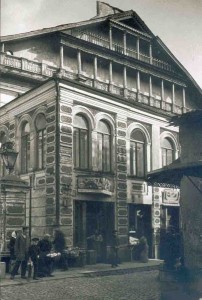

On the BBC set for “War and Peace.”

PHOTO: L. Lubamersky

In January 2015, the cast and crew of a BBC miniseries began filming an adaptation of Leo Tolstoy’s epic novel, War and Peace in Vilnius, Lithuania. Since much of the filming was done in Lithuania and many scenes were filmed just a few blocks from the apartment I was renting while on a Fulbright scholarship, I felt swept up in the action. It was also impossible to escape the irony of the fact that the actors were staging a re-enactment of a Russian imperialist tale on the very spot where that historical action actually took place, just at the moment in history when Putin’s Russia had begun re-claiming the memory of the Russian Empire and even engaging in military occupation of the lands that were part of the Russian and Soviet Empires by annexing Crimea and occupying Eastern Ukraine. Vilnius in 2015 was a dramatic place and time in history, both in fiction and in fact.

Vilnius makes a fabulous backdrop for a film about Napoleonic Europe, since some of its most beloved buildings, like St. Anne’s Church, were visited by Napoleon and the Grande Armée as it made its way toward Russia. But the tension between Russia and Western nations following the intervention in Ukraine was probably the real reason filmmakers chose Lithuania. Throughout most of its modern history, it was either a provincial city in the Russian Empire or one of the most well developed cities of the Soviet Union.

Old Vilnius

Old VilniusIt was not altogether certain when the BBC was planning the project whether Lithuania itself might become the target of Russian aggression. In January 2015, intense fighting was taking place in Donetsk, Ukraine, even after a cease-fire had been negotiated in September 2014, and Lithuanian diplomats were crafting a civil defense response should the country be invaded. Defense Minister Juozas Olekas said that “the examples of Georgia and Ukraine, which both lost a part of their territory, show us that we cannot rule out a similar kind of situation here, and that we should be ready.” Part of that preparedness plan was to distribute a manual instructing the population on how they should respond in case of Russian invasion, instructing them to resist foreign occupation with demonstrations and strikes and to organize themselves via Twitter and Facebook.

Though the major powers of Europe refused to describe what was going on in Ukraine as a war, Lithuanians viewed the situation otherwise. In Vilnius, the memory of Soviet occupation was fresh, having ended less than 25 years before. The very popular female President of Lithuania, Dalia Grybauskaite, stated that she would “take a gun (her)self to defend the country if that’s what’s needed for national security” and posted a photo of herself on Facebook at the firing range.

Grybauskaite was not about to limit her plans to defend against Russian invasion to civil defense plans and Facebook posts. She took concrete steps to place Lithuania on a stronger defense footing. First, her government banned the wearing of military uniforms by non-authorized personnel, in order to address the potential for the infiltration of “little green men” – Russian soldiers without insignia like those in Ukraine. Second, the government published civil defense information, but finally and most importantly she said that national conscription was “an absolute necessity” in response to the Russian threat, and her government proposed a national draft that was passed by the Parliament in March 2015. This raised the size of the army to almost 22,000 and called for men to serve a mandatory term of 9-month military service.

Old Vilnius

The Lithuanian government’s strong reaction against the Russian invasion should not have been surprising given the way that the Russians carried out the invasion of Ukraine – by using those “little green men” dressed not in the uniform of Russia but in unmarked camouflage. This was a covert action designed to effectively invade Ukraine without ever openly declaring war. The territory would be controlled by “Russian separatists,” but the invasion of Ukraine could not be directly traced back to Russia. This scenario had a haunting familiarity to Lithuanians, since a somewhat analogous situation took place in October 1920, when the Polish General of a volunteer army, Lucjan Żeligowski, pretended to desert from the Polish army in order to conquer Vilnius and proclaim a Central Lithuanian Republic, one in which the Polish nation would be predominant and in which Wilno would be a part of Poland rather than Lithuania. At that time, there was a Polish-speaking majority in Vilnius, many of whom supported Żeligowski’s coup, but the Polish government would deny involvement in the military action. In 1922, Poland would annex Vilnius causing Lithuanian politicians to move from a civic to an ethnic understanding of the Lithuanian nation, and damaging relations between Poles and Lithuania far into the future.

The stealth conquest and occupation of Eastern Ukraine by Russia in 2014 was not just a traumatic reminder of ethnic division in Vilnius of the past, it was an issue highlighting the division between the majority Lithuanian population and the ethnic minority Russian and Polish populations regarding the Russian invasion of Ukraine. A January 2015 poll showed that “55% of Lithuanian respondents blamed Russia for the conflict in Ukraine, (but) just 16% of national minority respondents (Poles and Russians) blamed Russia.”

The Polish minority is the largest ethnic minority group in Lithuania, making up roughly 7% of the population, with most Polish Lithuanians living in the Vilnius region. In the region surrounding Vilnius, Poles make up 52% of the population, but in the city of Vilnius itself, 16.5% of the population is Polish.

The two main reasons for this difference of opinion regarding Russian actions in Ukraine are that Polish Lithuanians speak Russian and watch Russian television as the main source of their information, and some of the more prominent leaders of the Polish Lithuanian community are openly anti-Lithuanian and pro-Russian since they view their constituency as not just the Polish minority, but also the Russian minority which makes up 6% of the Lithuanian population. Leaders like Waldemar Tomaszewski discredited the Polish minority in the eyes of the Lithuanian majority when “he condemn[ed] Ukraine’s Maidan protests and has been photographed wearing the black-and-orange St. George’s ribbon, a symbol of Russian imperial power (adopted by Russian-backed rebels in eastern Ukraine). But Waldemar Tomaszewski is not a rebel commander in the Donbas. He is the leader of the political party of Lithuania’s Polish minority, the Electoral Action of Poles in Lithuania (AWPL).” Tomaszewski supported Vladimir Putin’s narrative of events in Ukraine, and has even compared the Russian invasion of Ukraine to the USA’s intervention in Kosovo. Tomaszewski is a celebrated and very public leader of the Poles in Lithuania, but there are other more radical voices that engage in separatist advocacy on social media. On February 2, 2015 Gazeta Wyborcza reported about a Facebook group promoting the ‘Peoples’ Republic of Wilno/Vilnius’ demanding the deployment of “little green men” and organization of a referendum of the population’ in Vilnius and its surroundings.

Facebook pages were also created in Latvia, and Estonia calling for separatism in the Baltic states, so it is not clear who is running these Facebook pages, or even if Polish Lithuanians are connected with it at all.

AWPL party leaders rejected the Facebook page as a provocation, and there is little evidence of widespread support for separatism in the Polish population of Lithuania, but the Russian intervention in Ukraine exposed the fact that language continues to divide Polish Lithuanians from the majority population and reliance on Russian media shapes their perception of current events. And indeed it is not surprising that Poles in Vilnius might watch Russian television, (and I mostly watched Russian television while there) since Vilnius residents have access to a fast, highly competitive, and inexpensive broadband marketplace that includes access to Russian cable television, where the offerings are more attractive than Lithuanian television or TV Polonia.

It is not just Russian television that is attractive to viewers, but Russian culture attracted a worldwide audience in 2014-2015. Vladimir Putin went to great expense to attract international competitions like the Sochi Olympics and the 2018 FIFA World Cup in Russia to highlight the achievements of Russia. “Putin, like many autocrats before him, has concocted a toxic ideological cocktail of ethno-nationalism, Soviet nostalgia and Russian imperialism, to attract supporters for his regime in Russia in the former Soviet states,” and around the world. What could be a more attractive example of the achievements of Russian culture than the great 19th century novels like Tolstoy’s War and Peace, a novel that many Russians believe is the greatest novel ever written?

A ballet sequence from War and Peace was featured in the opening ceremonies of the 2014 Sochi Olympics, an opportunity for Putin’s government to package Russia’s culture in the way that they wanted the world to see it. “Russian viewers would associate the novel with the idea of nationalistic patriotism to which 1812 contributes. The older Russian generation also might well remember Stalin’s popularization of War and Peace during Hitler’s invasion to stir up patriotism and national morale.” Putin’s government is skilled at manipulating Russian culture to serve its own agenda, both at home and abroad, and the way that Russian nationalists currently use War and Peace is to stress the trope that Russia has historically been attacked from the West and that Russia is justified in seeking to re-establish a “border zone” in countries that have at one point or other been part of the Russian Empire or the Soviet Union. According to this construct, Russia merely engages in its own defense when it lays claim to countries on its Western borderlands like Ukraine, Poland, and the Baltic states. This is why the idea of a legitimate Russian buffer zone is such attractive propaganda – because it takes a kernel of truth: the fact that Russia has been attacked from the West – and it elevates this to a security doctrine which posits that the countries bordering Russia pose a threat to Russia by their independent existence. Dramatizing the heroic struggle of Russian patriots repelling the attack of their country from the West plays into the nationalist trope of modern Russian victimization at the hands of the West – whether it be at the hands of Napoleon, Hitler, or in the expansion of NATO.

St. Anne’s Church in Vilnius

But there is a problem with accepting uncritically that War and Peace was the struggle of the Russian nation against the invading French, because in Vilnius, the definition of who was the invader and who the invaded depends upon your perspective. The BBC miniseries presented Tolstoy’s narrative uncritically, accepting that the people in Napoleon’s army were “the French” who were facing “the Russians” defending their nation, but of course this is incorrect. The Napoleonic army was not French but multinational and at least some of them were from the Grand Duchy of Warsaw and they were fighting to restore the land that had only recently been partitioned by the Russian, Prussian, and Austrian empires. If one knew little about European history, watching the BBC series would cause one to believe that the people living in Vilnius were Russian, and that they fled as the army approached. But, of course, in 1812 the people of Wilno/Vilna/Vilnius welcomed the Napoleonic army and Napoleon himself. When Napoleon saw Vilnius, he loved it, since it still has one of the most perfectly intact medieval city centers in Europe. Of the lovely late-Gothic church of St. Anne’s, the Emperor is said to have remarked: “If only I could, I would carry it back to Paris with my own hands.”

When Napoleon was staying in Vilnius, the people who welcomed him were mostly Polish and Jewish. According to Leyzer Ran, Napoleon admired the Great Synagogue and “as he walked through the narrow medieval streets of Vilna, they reminded him of Jerusalem. From then on, one street actually came to be known as Jeruzalimska Ulitsa.”

Great Synagogue

The massive and impressive Great Synagogue was damaged by the Soviets during World War II, but not destroyed by the Soviets until 1957 when they constructed a school on the site. Tom Harper, the “War and Peace” series Director, chose to shoot some of the miniseries scenes on the adjacent street, Dominican Street. Filming took place by the Dominican Church of the Holy Spirit, one of the oldest churches in Lithuania, one of the few churches that continuously operated during the Soviet period and as center of Polish culture. While the church itself is beautiful and in top condition, what was the convent adjacent and the surrounding yard is still in ruins, and so the film crew was able to set up shop there in the dilapidated churchyard. So although the crew was filming surrounded by vestiges of Polish and Jewish culture, all of the multicultural richness of that space was excluded from the film. The people who had actually lived there were whited out in favor of a Russian nationalist narrative, and this is quite puzzling in the year 2015, when the postmodern era calls for inclusion and respect for multiple perspectives to allow for a fuller understanding of the past.

Palace in Rundāle

Other settings featured in the miniseries also were replete with multinational historical significance that did not make its way into the film itself. Palace scenes were shot in Rundāle, a spectacular masterpiece built between 1736-1740 for Count Ernst Johann Biron, the favorite of Tsarina Anna Ivanovna. The palace, now in Latvia, in the 18th century was in the Grand Duchy of Courland and Semigallia, a part of the Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth since the 16th century, but annexed by Russia in 1795. Village scenes were shot in Rumšiškės, located near Kaunas, an open-air ethnographic museum exposition of Lithuanian rural life. The villages of the Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth were multi-ethnic, with Lithuanian, Polish, Belarusian, Jewish, Russian, and even Scottish villagers living in a more complex mix of cultures than that featured in this monocultural museum setting.

Vilnius has been called “the city built on human bones” because it was both a battlefield and a zone of occupation, so many times over the course of two centuries. In 2002 while removing Soviet barracks for new development, the bulldozers unearthed a mass grave containing the remains of over 2000 soldiers who perished in the retreat from Moscow. While the “War and Peace” narrative would have one believe that Napoleon’s army was routed at Borodino once and for all, Napoleon claimed that he only retreated on account of extraordinarily bad weather. “Ever since, historians have been divided over whether Napoleon made the weather an excuse for his defeat to cover up strategic and tactical blundering.” According to Professor Olivier Dutour, a forensic exhumation expert, the Vilnius discoveries vindicate the diminutive megalomaniac. “The results confirm the extreme cold at this period. Napoleon claimed that he ordered the retreat because of the cold. And it’s clear that some of the corpses really were frozen solid when they died in temperatures of -40C. It was like being in a deep freeze.’”

The multinational teams of researchers concluded that these were the remains of people who died of hypothermia, starvation, and typhus, who were probably buried in defensive trenches that they dug to defend the city. Approximately 20,000 people died in Vilnius but their remains have yet to be unearthed.

“War and Peace” is a beautiful, entertaining, lavish production, and very well received throughout the world, airing first on the BBC and on three cable networks in the USA in January 2016. Even though it has never been shown on Russian television, Russian viewers somehow found a way to check it out on the internet, and, for the most part, gave it their stamp of approval, though it lacks a “reverent attitude.”

It is wonderful that the beauty of Vilnius and Lithuania could be showcased in this series and I watched every minute of it with pleasure. But I cannot help but feel that it was a guilty pleasure, endorsing patriotic mythology in an age of resurgent Russian nationalism. I cannot help but wonder how the people of annexed Crimea and Eastern Ukraine might feel about it, and if the people of the Baltic states might wonder if they will soon be drawn into another epic saga of war and peace in the western borderlands of Russia.

CR

Pingback: Welcome to Spring 2016!

Interesting article, partly because it is a good article and partly because I am just now reading “War and Peace” for the first time. Because of the reputation of the book as a literary masterpiece, I am amazed at how much like a soap opera it reads and how much it is a family saga, which it is. The article points out the incredible complexity involved in understanding the history of Lithuania, Poland, the Napoleonic Wars etc. My Polish father, born in Azerbaijan (just to show how complex the stories are) would have said that without a good shot of vodka you couldn’t possibly understand the history. This from a man who went off to fight WWII in September 1939 on a horse as a member of the 10th Lithuanian Lancers which was of course, part of the Polish Army. So, in may ways how you see the Napoleonic Wars, Lithuanian-Polish relations, and today all depends on which side of the equation you were on. To Tolstoy, Napoleon and his army are the embodiment of evil, while the Russians are the good guys, although to give Tolstoy his due, he paints fools on all sides and shows them all as pawns of history and of the human story. To Poles, like my father, Napoleon was the potential saviour of Poland, although he clearly let all Poles down. My Father was an ardent Polish nationalist, but felt that Wilno / Vilnius was and is a Lithuanian city and should have been left to Lithuanian in the 1920s. He too decried the damage done to Polish – Lithuanian relationships as do I. It is very saddening to read about contemporary movements to return Vilnius and area to Poland. Sorry, Leo Tolstoy, but it seems that in spite of your best efforts to teach us about history, we have learned nothing and we are doomed to repaet it.

Dear Stan Skrzeszewski, Thank you for your thoughtful response to the article. I’m sorry if it seemed that there are significant movements afoot to return Vilnius to Poland, since I don’t think that this is the case. The only real movement to revise post WWII borders has come from Putin’s government in its annexation of Crimea and occupation of Ukraine, so I did not want to leave the impression that Poles in Lithuania are separatist. Poles in Lithuania do face real challenges to their human/educational/civil rights which might lead them to frustration with successive Lithuanian governments. To a citizen of the USA, it is outrageous that Lithuanian governments prohibit Poles from using their own names on the pretext that such letters do not exist in the Lithuanian language. For example, a woman named Wanda Wilk could not call herself that, by law. She would have to be Vanda Vilkaite or Vanda Vilkiene. It is a fundamental human right to be able to call yourself by your own name, so Poles face discrimination in Lithuania, but I did not see serious contemporary movements to return the Vilnius area to Poland.

Ms lubamersky,

I frankly was rather intrigued by the recent BBC series and being on a flight to China via Doha I had 24 hrs to kill and watched the first 4 episodes. My love of architecture and interest in the social protocols of the nobility have led me to do a bit of reading about the era.

Thank you for your eye opening perspective on the historical nuances of the time.

You should be writing for the Brookings Institute as I did enjoy your thought provoking analysis of state Russian propaganda. The current “toxic Russian ideological cocktail of ethno nationalism, Russian nostalgia, Russian imperialism” reminds me of the ideological underpinnings of the Trump Campaign.

Strange “build this wall” seems to be the opposite of Reagans “tear down this wall” and it shows how we both East and West are falling back into the politics of fear.(and the sheep are buying it)

Please forward any of your other articles web connects that you may have.

Regards, Greg

Dear Greg,

You are very kind. Thank you. -Lynn