A long, long time ago and far, far away – across oceans and plains and mountains – herds of animals once roamed wild across the forests and fields of Europe. Wooly, craggy bison; long-limbed stallions and mares; sharp-eyed wolves. And tarpans. Small horses, grey in color with distinctive striping on their legs and back. Documenting these “warm, friendly, curious, extremely intelligent but stubborn” creatures in 1789, German explorer Samuel Gottlieb Gmelin would estimate their height at 13 hands (compared to an average horse’s 15).

A long, long time ago and far, far away – across oceans and plains and mountains – herds of animals once roamed wild across the forests and fields of Europe. Wooly, craggy bison; long-limbed stallions and mares; sharp-eyed wolves. And tarpans. Small horses, grey in color with distinctive striping on their legs and back. Documenting these “warm, friendly, curious, extremely intelligent but stubborn” creatures in 1789, German explorer Samuel Gottlieb Gmelin would estimate their height at 13 hands (compared to an average horse’s 15).

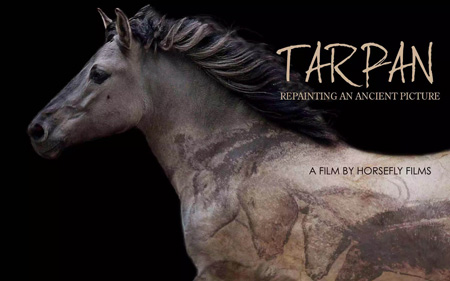

Less than a century after Gmelin wrote those words, the tarpan would be extinct. But by the mid-20th century, a modern tarpan would be resurrected – thanks to the work of Polish scientists after WWII. Today, herds of these animals live in various Polish nature reserves and stud farms. And recently, two small herds have begun to roam wild in a remote corner of Bulgaria. They’re part of a project, “Rewilding Europe,” that’s seeking to do just that. Filmmakers Jen Miller and Sophie Peregrum spent 10 days in the small village of Sbor filming the animals for their latest project, “TARPAN: Repainting An Ancient Picture.”

The film tells the story of “mankind trying to save something,” Sophie says in a phone interview. “But the interaction between mankind and this horse is part of a larger story: We drive things to extinction and then we try to save them. We use nature and suddenly – it’s gone. Now what do we do about it?”

The film tells the story of “mankind trying to save something,” Sophie says in a phone interview. “But the interaction between mankind and this horse is part of a larger story: We drive things to extinction and then we try to save them. We use nature and suddenly – it’s gone. Now what do we do about it?”

Tarpans date back to the Pleistocene era, 10,000 – 13,000 years ago, and are considered one of four main ancestral groups of horses.

Poland has figured prominently in the history of the tarpan – and especially its return. The last domesticated tarpan went extinct in Poland around the end of World War I, in 1918 or 19191. As elsewhere across Europe, social changes, massive industry booms and deforestation were systematically wiping out many natural habitats. And the first world war, like all wars, impacted all life forms.

But decades later, small horses with tarpan characteristics were discovered roaming the Polish countryside. Biologist Tadeusz Vetulani gathered these animals and bred them on a reserve he’d founded in Białowieża Forest. He called them “konik,” which means little horse in Polish. Most of the koniks perished during World War II; by 1945, only 15 were alive. They were passed onto the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences. And it’s these animals that are the most enduring modern link to the tarpan. (“Thank God for the Poles!” Jen says. “The konik would not exist if they hadn’t said, yes, we’ve always had them and we’ll continue to have them.”)

But decades later, small horses with tarpan characteristics were discovered roaming the Polish countryside. Biologist Tadeusz Vetulani gathered these animals and bred them on a reserve he’d founded in Białowieża Forest. He called them “konik,” which means little horse in Polish. Most of the koniks perished during World War II; by 1945, only 15 were alive. They were passed onto the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences. And it’s these animals that are the most enduring modern link to the tarpan. (“Thank God for the Poles!” Jen says. “The konik would not exist if they hadn’t said, yes, we’ve always had them and we’ll continue to have them.”)

Genetically, koniks are about 94% tarpan – at least, that’s what the various scientists who have studied them say. “[The scientists] are very reluctant to quantify, but that’s the estimate,” Jen says. “Unless we get our hands on a specimen.”

Genetically, koniks are about 94% tarpan – at least, that’s what the various scientists who have studied them say. “[The scientists] are very reluctant to quantify, but that’s the estimate,” Jen says. “Unless we get our hands on a specimen.”

Ah yes, that elusive specimen. The last wild tarpan is purported to have died in 1879 in an area of Poland then ruled by Russia. She was taken somewhere – and possibly preserved, or not. “She’s one of those specimens locked up in a museum or archive somewhere in Russia that scientists would love to get their hands on to finally quantify how related the konik is to the tarpan,” Sophie says.

When I venture that perhaps this specimen doesn’t even exist anymore, both filmmakers say they’re just not sure – it could simply be gathering dust and moth-eaten in a faraway basement.

“People weren’t thinking about DNA” back in the day when the mare was captured, Jen says. So even if the specimen were located, it may not contain anything viable, especially if it was stuffed and mounted.

“People weren’t thinking about DNA” back in the day when the mare was captured, Jen says. So even if the specimen were located, it may not contain anything viable, especially if it was stuffed and mounted.

That, right there, is a huge part of the documentary: The effects that past actions, often made arbitrarily and with no cognition of the future, have today. And what’s being done – and can be done – to rectify, if a rectification is even possible.

Which brings us to Rewilding Europe (“we are working to make Europe a wilder place. A continent that allows for much more space for wildlife, wilderness and natural processes,” reads their website) and Bulgaria.

The first 12 animals were bred in the Netherlands and Bulgaria from Polish koniks. They were brought to an abandoned Bulgarian village in September 2011 by a team of international conservation organizations. The koniks were first held in a 30-acre holder – located in a remote valley in the Rhodope Mountains – that was slowly increased in size. In 2012 they were released into the wild.

The first 12 animals were bred in the Netherlands and Bulgaria from Polish koniks. They were brought to an abandoned Bulgarian village in September 2011 by a team of international conservation organizations. The koniks were first held in a 30-acre holder – located in a remote valley in the Rhodope Mountains – that was slowly increased in size. In 2012 they were released into the wild.

The animals are wonderful, and Jen and Sophie are marvelous at capturing them at play or at rest, running around and nipping each other, and even giving a little muzzle cuddle to a dog. They graze, and bathe, then graze some more.

And although Jen and Sophie’s specialty is filming all things equine, this project was challenging, both say. “Just getting out there was a journey. And then of course finding the horses,” Sophie says. “They’re on a huge piece of land. We’d go tramping off into the countryside and didn’t know what we’d get.”

And although Jen and Sophie’s specialty is filming all things equine, this project was challenging, both say. “Just getting out there was a journey. And then of course finding the horses,” Sophie says. “They’re on a huge piece of land. We’d go tramping off into the countryside and didn’t know what we’d get.”

Even once they found the horses, the animals wouldn’t necessarily be doing anything interesting. Eating, for example. “This is not cinematically compelling,” Jen says. “And you don’t want them not to eat. But how long can we photograph them eating?”

One of the most beautiful scenes in the film shows the tarpans playing in a pond. “They were halfway down the mountain at that point,” Sophie said. “We jumped out and it was a few moments of capturing them on a really long lens.”

Jen and Sophie also had to be careful to not get too close, as the horses’ keepers don’t want them to socialize with people too much. “They’re not cute little pets,” Sophie said.

When the keepers talk about a wolf attack in the film, my heart sinks. The first year the horses arrived, a two-year-old filly was attacked and killed, and all the big horses were bitten. The tarpans had never come into contact with a predator, and simply didn’t know what to do.

When the keepers talk about a wolf attack in the film, my heart sinks. The first year the horses arrived, a two-year-old filly was attacked and killed, and all the big horses were bitten. The tarpans had never come into contact with a predator, and simply didn’t know what to do.

And yes – that’s the way nature works. “But knowing the horses hadn’t adapted to that yet – that’s the poignant part of the story,” Sophie says. The horses are wild, but not entirely. And they’ve had to learn about their new system. “That little foal had no idea,” she says. “And the rest of the herd had no idea how to protect it. That’s a tough, harsh lesson to learn.”

And there’s that push-pull between what’s natural and what’s unnatural; a horse that has been bred from once-wild horses but has never experienced what being attacked means. Attacks that are normal in a larger ecosystem, but still a huge shock in this fragile, smaller one.

Smarties that they are, the horses did learn from that attack. They stayed away from the area the attack happened for a month, were skittish, afraid of everything. But then they went back. And now their numbers are bigger, and will continue to grow. Last year, another herd of 35 was brought in.

“This concept of re-wilding is a bit new,” Jen said, “but in a short time this’ll be the norm.”

Since the film was released in late 2014, the filmmakers have been approached by various groups and individuals interested in the concept of re-wilding. Jen and Sophie’s hope is that their film – and work – can be a bridge.

“We want to tell these stories,” Sophie said. “We’re not giving definitive answers but we are hopefully building cultural bridges.”

CR

READ about Re-Wilding Europe

CHECK OUT Jen and Sophie’s website

ENJOY the Bulgarian konik photos on this page, courtesy of Horsefly Films

- The Polish Count, Jan Zamoyski, acquired the last wild tarpans around 1780, where they thrived on his huge reserve in eastern Poland. But in 1806, he turned them over – now domesticated – over to the local populace. In the film, the narrator says that Zamoyski had “lost interest in keeping bloodlines pure.” When I asked the filmmakers about this, Sophie said she thinks his decision had a lot to do with a society that was changing. Aristocracy had to cut back, and as time went on, they didn’t necessarily have money to keep up the tarpans. “They’re not looking 100 years into the future,” Jen added. “It was about their bottom line.” ↩

The (3) partitions of Poland (and its oppression) occurred during the time the author shares Count Jan Zamoyski’s involvement and subsequent liquidation of his band of Tarpans.

There were many Count Jan Z’s. Are his middle names available so I can find him in our genealogy?

No, I don’t have Count Jan Zamoyski’s middle name.

Hello. Here you can see nazwyanego Polish Tarpan horse. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XBsq7lf-56U

Our family raised polish Arabians for a while the 1970’s and Although they were very intelligent they were extremely stubborn we were raising them to be equestrian jumping horses but it didn’t work out so well since they were so short but I found them to be beautiful and majestic and elegant