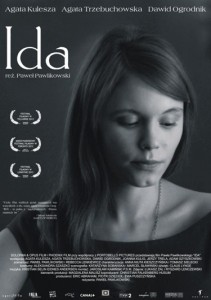

Ida

Ida

Directed by Paweł Pawlikowski

2013

I was elated when I received CR’s offer to review Paweł Pawlikowski’s Ida. Nominated for a handful of awards at Poland’s prestigious 2013 “Orły” Awards, the film won Best Film, Best Director, Best Actress in a Leading Role, and Best Editing. My Facebook feed was full of praise for the film from my Polish friends, and I was happy to have a chance to see it so soon after its release. My first impression of the film was highly favorable and, in truth, I was somewhat awed. Upon a second viewing, however, the nuances of the film, both its problems and its more subtle virtues, became apparent.

Still from Ida, dir. Paweł Pawlikowski, photo: Opus Film

“Sister Anna,” played by newcomer Agata Trzebuchowska, is preparing to take her vows when she is told she has one living relative and that she must spend time with her before she will be allowed to become a full nun. She leaves the convent to meet her aunt Wanda, portrayed by Agata Kulesza, for the first time. When she arrives, Anna must cope with revelations about her past, her identity, and that her name is not Anna, but Ida… and that she is Jewish. Hidden in a Catholic convent during the war, Ida survives while the rest of her family (save Wanda) perishes at the hands of their Polish neighbors. Wanda, an unhappy, hard-drinking, former Stalinist prosecutor who later wistfully recounts time spent as the infamous “Krwawa Wanda” (Bloody Wanda), is now a local judge and (as she bitterly mutters later in the film) a “nobody.” The true action of the film begins when the unlikely pair travel to a small town in the Lubelszczyzna region in order to interrogate the family now living in their pre-war home and to find the graves of Ida’s parents.

Still from Ida, dir. Paweł Pawlikowski, photo: Opus Film

The film is starkly beautiful. The decision to film the movie in black and white results in contrasts that highlight the intense textures of the landscape. Given the backdrop is 1960s Poland, the color palette is well-suited to the dilapidated buildings, the depressing bus stations, the empty restaurants. Even so, the film is breathtaking. Each shot is meticulously composed, and often seems more photographic, or even painted, than cinematic. Many camera shots de-center the actors, and much of the action of the film takes place in the lower half of the screen. This tactic creates a sense of vast space, but also a weightiness that imbues each carefully-crafted scene with gravity. The weight of things left unsaid between the women and the Poles they encounter, of a national history alluded to but never explicitly revealed, is perhaps symbolic of an unseen divine presence? The film itself gives no definitive answer.

Still from Ida, dir. Paweł Pawlikowski, photo: Opus Film

Agata Kulesza’s performance absolutely blew me away. I must admit a bias towards Kulesza, as she’s been my Polish-celebrity-crush since I first saw her in Jan Komasa’s Sala Samobójców in 2011, but I think her recent award for Best Actress justifies my admiration for her performance in Ida. Whereas Trzebuchowska’s expressions seem contemplative, unreadable, or even flat at times, Kulesza’s face betrays her bitterness, anger, and desire for impossible restitution. One scene that particularly struck me was when Wanda and Ida arrive in the village and confront the family that hid, and apparently murdered, Ida’s parents. Wanda’s pointed questions and quietly delivered threats betray her prosecutorial past, but her body, although completely still, radiates a cold, sharp rage. The scene sent shivers down my spine, but also showcased Kulesza’s ability to deliver an incredible depth and complexity of emotion in a minimalist fashion.

Still from Ida, dir. Paweł Pawlikowski, photo: Opus Film

The film’s subject matter itself is highly emotional, but the quietness of the film – the stationary camera shots, the minimal dialogue, the extended silences, the lack of non-diegetic sound – turns it into an intellectual or aesthetic journey rather than a touching or sentimental one. The trauma of the war lurks in the background but only emerges sporadically; the pain of Polish-Jewish relations is subordinated to the pain of individual loss and regret. Perhaps this is why critics praise the “universality” of the film – the filmmaker’s concentration on the two protagonists and their struggles with the past, with each other, and with themselves, coupled with the fairly obvious but painstaking attention to aesthetic detail, appeals to audiences across the globe.

Still from Ida, dir. Paweł Pawlikowski, photo: Opus Film

The intense beauty of the film has raised some thorny questions amongst critics, however. Can a film aestheticize the Holocaust, or more specifically, the complexity of 20th century Polish-Jewish relations? What are the consequences of doing so? And more broadly, can a film, or any art form, be truly apolitical? Answers to these questions were heatedly debated in the Polish press.

Some critics argued that the film’s beauty was paramount and that it should be judged solely on its considerable artistic merit; others pointed out that the aesthetics drew attention away from problematic representations of Jewish characters and reduced the very real, very painful history of Polish-Jewish relations to an attractive story. The film is inherently political, they argue, precisely because it tries to foreclose a debate about Polish-Jewish relations and replace it with a debate about “art.”

I tend to side with the latter argument, largely due to my own overwhelmingly positive first impression of the film’s aesthetic composition. It blinded me somewhat to the problematic treatment of Polish-Jewish relations.

Whatever your thoughts are about the role of art and history, the film is nevertheless worth seeing, if only to contemplate these issues. It truly is a beautiful film, and while it is important to recognize its problematic representations, it remains for me one of the best Polish films of 2013.

CR

WONDERFUL review about a very troubling subject. It reminds me of William Faulkner’s comment about the America South, as a place where the past is never over; in fact it is not even past.”

Kkeep up the good work with your Polish language studies at the Jagiellonski and with your Ph.D. I was a Polish language student at the Jagiellonski a coupla decades ago so I appreciate your studies all the more so. For me that year in Krakow was a time of very great experiences and impressions about life in Poland.

best regards

Pozdrow

Bernie Behrens

Pingback: Welcome to Winter 2016!

Pingback: The Politics of Morality: The Church, the State, and Reproductive Rights in Postsocialist Poland