OJCU

OJCU

Written and Directed by Liliana Komorowska and Diana Skaya

Executive Producers: QueenArt Films and Di Sky Productions

Co-producers: QueenArt Films Inc. i Telewizja Polska S.A.

Director of Photography: Jan Belina Brzozowski

2015

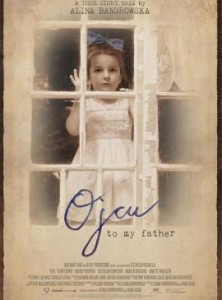

In 1938, a little girl, Alina Bandrowska, saw her father arrested by the NKVD, the Soviet secret police. He never returned. Alina and her mother left their home to live with an aunt who took them in but warned them never to speak of this. So they lived in silence, and decades later, in a country far from Ukraine, Alina wrote a poem about her father. This poem inspired a beautiful short film, Ojcu (To My Father), screened at St. Paul University in Ottawa on November 15, 2016.

The destruction of nations comes in two stages. First there is the physical destruction through war, arrests and executions, ethnic cleansing and deportations. The second part is the destruction of historical memory. To this end, powerful states use all the means at their disposal to control the press, education, the arts, and even free speech among friends or family. A child’s innocent remark outside the home could lead to another arrest.

But they can’t stop a child from writing a poem or, decades later, stop a young woman living in Canada from making a film about her beloved aunt Alina. Memory has a way of eluding the censors.

The Bandrowski family was part of the large Polish community that remained in the part of Ukraine that was once part of Poland but was incorporated into the Soviet Union after the Bolshevik revolution. They stayed there because that was their home, the place where their families had lived for generations.

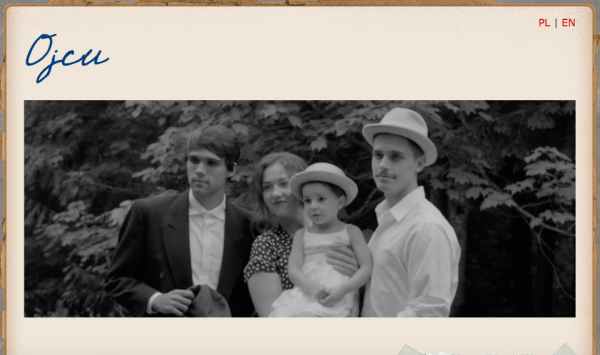

The story told in Ojcu begins in 1938 when Adam Bandrowski is a young man, the husband of Jadwiga, the father of a little girl, Alina, and a professor at an agricultural college. They lived in Vinnytsia, in the Ukrainian republic of the USSR. Little Alina’s poem says nothing about the politics of the time but only about her family, their love, their joys, gatherings of friends around a picnic with songs and dancing, and a memory of dancing in the arms of her parents in her pretty summer dress with a garland of flowers in her hair.

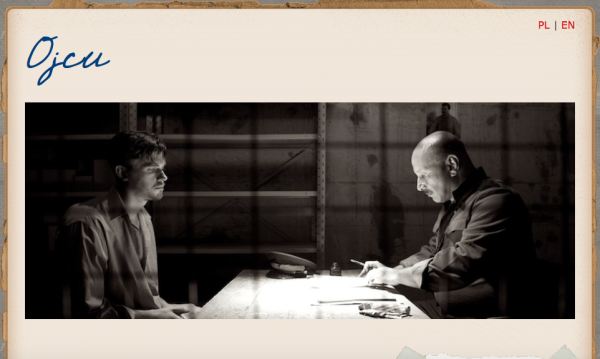

But these happy memories come to an abrupt end when soldiers come to the house in the middle of the night and take her father away. She remembers her mother trying to see her father at the prison, or at least to bring him a letter and some clean clothing. On one attempt, the NKVD stopped that too, telling her he had been sent away to a labour camp, so her mother comes home with some of Adam’s belongings, among them his blood-stained shirt. The family suspects he was executed, but Adam’s death sentence is confirmed only in 1943 during the German occupation of Vinnytsia. After Stalin’s death, the family learns of Adam’s “rehabilitation,” the Soviet Union’s way of declaring an executed person had not been guilty of any crime, when Nikita Khrushchev takes control of the USSR and reveals Stalin’s murderous record.

The film is narrated by Alina, who speaks Polish with the lovely lilting accent of the Kresy, the eastern provinces of Poland. The family scenes, well acted by actors from Montreal of Polish, Ukrainian and Russian origin, are beautifully filmed in black-and-white by the very talented cinematographer, Jan Belina Brzozowski, a Montrealer and a graduate of the Polish National Film School in Łódź. The family story is filled out with photographs of documents including those confirming Adam’s arrest, sentence, and subsequent “rehabilitation.” Contemporary scenes include Vinnytsia’s Gorky Park, which covers the bodies of over 13,000 victims from this region. Only now are people realizing what lies beneath, a truth Russia’s current dictator, Vladimir Putin, would prefer not to acknowledge. Although Ojcu is about events outside contemporary Poland’s borders, it is nevertheless an important part of the story of the Polish nation, and yet so few people in the largely Polish audience were aware of these events, part of Stalin’s “Great Purge” of the 1930s, in this case the “Polish Operation” when he ordered the liquidation of the Polish presence in the USSR. Eventually the NKVD murdered over 100,000 and arrested many more.

This review would not be complete without a word about the directors. Diana Skaya is an Armenian-born Polish-Canadian, now living in Montreal with her mother and her aunt, Alina. Diana, who grew up speaking Polish, Armenian, Russian and Ukrainian, and now has added English and French to her linguistic skills, knows the various strains of her history and has a passion for bringing them to film. In this, she should be a model to other young writers or filmmakers because it is this inclusive history that is valuable. The stories of the nations subjected to Russia’s imperialism are often intertwined and a narrow, nationalist version is never entirely truthful, and frequently boring. A nationalist government can order it, but it will never produce anything worthwhile. I look forward to her next film, which will focus on her Armenian heritage.

A film is always a collective undertaking and Diana was fortunate that her passion came to the attention of another Montrealer, Liliana Komorowska. As co-Director, she brought her experience and her contacts to the project to create the screenplay and find the people to create it. An accomplished actress both in her native Poland and in the US and Canada and a filmmaker, Liliana also established The Liliana Komorowska Foundation for the Arts to support Polish artists in Montreal.

Diana and Liliana acknowledge the many people who supported this film but I want to point out someone I happen to know was the first to encourage Diana at an early stage, the former Consul-General of Poland in Montreal, Andrzej Szydło. I hope many more people, both in the Polish government and in the widespread diaspora, will encourage independent writers and artists. It is the collection of the many stories that will overcome the destruction of historical memory.

CR

I am sooo very impressed by your great achievements, you are amazing! I miss you all dearly. I hope to see you again soon, I am unfortunately fighting cancer, which has kept me away. My apologies 😕

❤❤❤❤❤