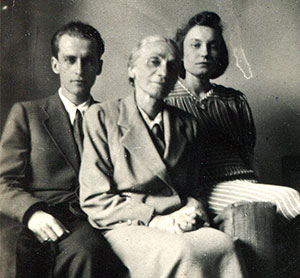

Krzysztof Kamil Baczyński with his mother,

and wife and muse Basia née Drapczyńska. ~1942

August 4, 1944. On only the fourth day of the Warsaw Uprising, the poet Krzysztof Kamil Baczyński was killed by a German sniper in the city’s Old Town. Less than three weeks later, his wife and muse, Barbara (née Drapczyńska), pregnant with what would have been their first child, was mortally wounded when a shard of glass pierced her skull. She died on September 1. He was twenty-three; she, not yet twenty-two. Their deaths remind us how subtle is the physics that gives us one literature instead of another. Forget about the long timelines and distances, the careful deliberations and repeated trials we might otherwise associate with the creation of an artwork and the culture it helps compose. We’re talking about split-seconds and fractions of an inch, lucky shots and random shrapnel.

That it has been shaped by its history is about as banal a thing as one could say about Polish literature, or any other. But just as history is the name we give to a certain way of looking at events, one that necessarily arranges and edits in order to craft a narrative that helps us make sense of them, the life of the author constitutes a text that we read alongside, within, or against his or her written oeuvre. Baczyński offers us a prime example of life as literature. In 1944, he joined a pantheon of Eastern European writers whose activities on this earth have been largely circumscribed by their manner of leaving it.

This is but one respect among many that might classify Baczyński as a modern instantiation of a Romantic poet. Not a Neo-Romantic poet, mind you—one of the partisans of the Parnassian “art for art’s sake” who, through such strong personalities as Stanisław Przybyszewksi and Stanisław Wyspiański, defined the fin-de-siècle in Polish literature. Nor a poet in the mold of Julian Tuwim or Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz, whose influential interwar journal Skamander eschewed avant-garde experimentation in favor of a more traditional, accessible lyricism. Baczyński did not belong to these schools, if indeed we can say that he belonged to any school at all, though like many writers and artists he did find personal and creative refuge from the war at Stawisko, the Iwaszkiewicz estate outside of Warsaw. There, in 1942, he wrote these lines to Barbara, which open one of the many erotic poems that would rank among his most beloved:

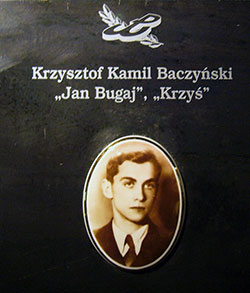

Krzysztof Kamil Baczyński’s tablet in the Warsaw Uprising Museum; it bears his Resistance aliases, ‘Jan Bugaj’ and ‘Krzyś.’

Madonno moja, grzechu pełna,

w sen jak w zwierciadło pęknięte wprawiona.

Duszna noc, kamień gwiazd na ramionach

i ta trwoga, jak ty—nieśmiertelna.

—”Noc”

O my Madonna, in sin most fertile,

you’re set in dream as in a shattered mirror.

The stifling night, a stone of stars upon your shoulder

and this terror, like you—immortal.

— “Night”

Thus, in a post on Facebook—a veritable untapped goldmine of critical insight—Magda Romańska recently characterized Baczyński as “Bob Dylan, William Shakespeare, Pablo Neruda and James Dean rolled into one.” In other words, a Romantic par excellence.

For me, though, the point of Western comparison would have to be John Keats. Keats-Baczyński, whose erotic longing grows in proportion to his distance from its object. Keats-Baczyński, drawing inspiration as much from the constancy of natural cycles as from the scattered artifacts of civilizations past. Keats-Baczyński, desirous to overcome physical sickliness through an exercise of will. Keats-Baczyński, whose early death punctuates brief years of feverish activity—literally for Keats, dying of consumption. Baczyński’s own difficulty breathing was due to severe asthma, which, coupled with his intensely doting relationship with his mother, prompted Czesław Miłosz to characterize Baczyński as a Polish Marcel Proust.

While all of his mature work was produced under the struggle against Nazi occupation, Baczyński was not fundamentally what one might call a “war poet.” Even in poems addressed to his beleaguered nation, Baczyński seems to have in mind the Romantics’ idea of fatherland, a place to be found within the soul itself, a land tread more easily with the foot of verse than the one to be found at the end of the leg:

Kto ciałem, temu kat obcina głowy taran,

kto duchem, temu kat nie zetnie głów płomienia,

bo gdzie się kończy zbrodnia, tam się zaczyna kara,

i tam zaczyna niebo, gdzie się kończy ziemia.

—”Prolog (Ojczyzna)”

Who is a body will lose his head to the hangman’s hand,

who is a soul, the hangman won’t behead his flames,

for where the crime is finished, the punishment begins,

and heaven begins there, where also ends the land.

—”Prologue (Fatherland)”

Krzysztof Kamil Baczyński

~1944

In Baczyński we have a poet whose work and life seem to make manifest what the Romantics of the previous century—and especially Juliusz Słowacki and Cyprian Norwid, whom he greatly admired—tended to idealize, namely: sublimity among the ruins. He was unequivocally the most talented lyricist of his generation, his breezy self-confidence belying his fondness for surprising rhymes, dense wordplay, and a rhythm that is often as heavy as “The hexameter of Latin waves against the setting sun.”

It is no wonder that Baczyński’s poems, composed at an improbable rate, have been a favorite among musicians, who have been eagerly setting his words to music since the mid-1960s. His gorgeous lyrics on the passing of the seasons, on solitude and longing, on death and the struggle for both individual and collective being—all signature themes of Romantic poetry—have secured him an enduring legacy in Polish letters. His early death, with all the Romantic trappings of a patriotic cause and young love cut tragically short, has made him legend.

CR

Pingback: Welcome to our 2014 Fall-Winter Issue!

Pingback: This Day, August 4, In Jewish History by Mitchell A. Levin | luach.eu

This was exciting to read as our name is Baczynski my fatherinlaw name was Wasyl. Our family emigrated to Canada in May 1948 from a DP camp in Germany.They settled in Sault Ste Marie worked at Algoma Steel. my husband Michael Wm Baczynski was conceived in Germany but born in Canada in Aug. 1948. We would like find out if we are related to this poet.thank you for the post