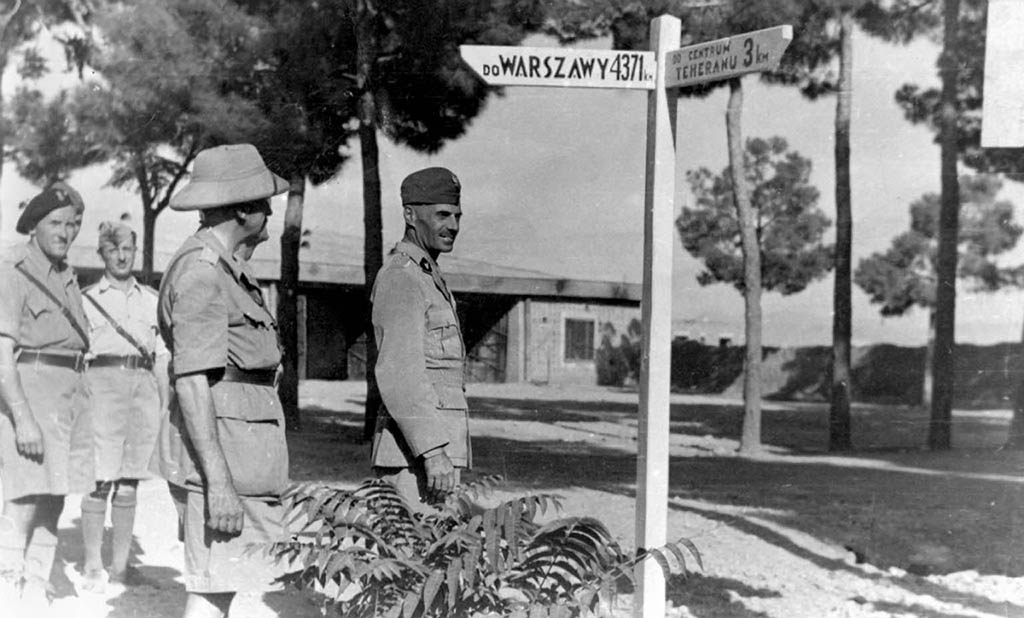

Henryk Wars in Teheran; 1942

An extraordinary publicity photo taken in 1942 presents the famous composer Henryk Wars standing before his eighteen-piece “Tea Jazz” Orchestra. Wars squints in bright sunlight, clad in a full-dress uniform. Some of the musicians behind him have changed into short-sleeved army shirts. The conductor and his big band are no longer poised to perform in temperate Warsaw, but in hot, arid Teheran, attached to the Polish II Corps under the command of General Władysław Anders, a fighting force popularly known as the Anders Army. The photo, framing the band, leaves us guessing about the people sitting behind the camera. Wars and the Tea Jazz Orchestra might have been playing for officers and soldiers of the II Corps, Persian dignitaries, or a combined public of British, Australian, and Polish troops. General Anders was pleased to show off his accomplished “theater units” before Poland’s allies. Long before his troops were ready for combat, these entertainers demonstrated the world-class calibre of Polish stars in battledress.

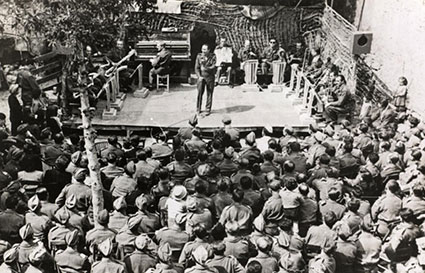

A note on the photo reads, Outdoor Mass with the participation of Gen. Anders on Independence Day, Nov. 11, 1945 in Buzulk.

How the Anders Army came to travel with its own stable of professional performers is a complicated story – logistically, professionally, and politically. The very formation of the II Corps was something of a miracle, for it emerged from forced captivity on Soviet soil. For the two years that Nazi Germany and Stalinist Russia jointly occupied Poland under the terms of the Molotov-Ribbentropp pact (1939-1941), Soviet security forces had arrested and deported roughly a million Polish citizens from the eastern territories to labor camps in Siberia and the far north and collective farms in Central Asia. When the Germans invaded the U.S.S.R. in June 1941, the Soviet government agreed to amnesty these so-called Polish enemy aliens and allowed the creation of an independent Polish army within its borders. The recruiting centers in the provincial mudholes of Buzuluk, Totskoe, and Tatishchevo drew desperate, eager soldiers and their families from all over the Soviet Union. It immediately became clear that the Anders Army not only had to outfit and train these emaciated, disease-weakened recruits, but also had to feed and care for soldiers and civilians. From the outset, the II Corps functioned as a self-supporting Polish diaspora marching towards repatriation.

Most of the professional entertainers who made their way to Buzuluk, Totskoe, and Tatishchevo were not deportees, but refugees from Poland’s capital. Their special status requires careful explanation. Many of the Varsovian cabaret and revue artists who fled east were acculturated Jews. They harbored no illusions about exceptional treatment under a Nazi occupation, and they chose instead a very uncertain refuge in Soviet-held territory, particularly in Poland’s second great entertainment capital, the city of Lwów. Lwów served as a critical waystation for Jewish composers such as Wars, Henryk Gold, Jerzy Petersburski and Alfred Schütz; Jewish director/actors such as Konrad Tom, Ludwik Lawiński, and Kazimierz Krukowski (creator of the beloved Jewish cabaret character “Lopek”); and Jewish singers such as the young Gwidon Borucki and the established Zofia Terné (“the Warsaw nightingale”).1 The theaters, cabarets, and musical ensembles mushrooming in Lwów likewise attracted non-Jewish talent – most notably, the screen and stage star Eugeniusz Bodo, the writer Feliks Konarski and his comedienne wife Nina Oleńska, and the lovely young contralto Renata Bogdańska, who eventually became General Anders’s wife. Varsovians dominated the ranks of refugee artists since most native Lwów performers had evacuated to the west along with other branches of the Polish army earlier in the war.

A young Renata Bogdańska.

Warsaw’s artists also opted to work in Soviet-held Lwów because of their relatively good treatment by Soviet authorities, fellow artists, and audiences. The authorities welcomed performers of any religious background, be they Jewish, Roman Catholic, or Russian Orthodox, provided that they delivered good shows and ostensibly promoted an apolitical, Soviet-friendly Polish culture. In Lwów entertainers were divvied up into different ensembles, which then toured ever further east. Gwidon Borucki remembers the many months they spent riding the rails, performing in cities all over the Russian republic. After the German invasion, the Polish ensembles were shunted away from the front to tour Central Asia.2 Traveling conditions were rugged, and each ensemble’s Soviet “managers” monitored the players’ behavior and censored material as instructed.

Yet these refugee artists did enjoy a certain camaraderie with their Soviet counterparts, talented musicians keen to work with experienced performers of western jazz. Jerzy Petersburski’s songs were quickly appropriated and performed by Soviet bands, with the composer’s permission. Wars’s Tea Jazz Orchestra won enormous popularity everywhere they played in the Soviet Union. Hanka Ordonka, another Varsovian star who had come to Russia by a different route, took the Moscow stage by storm, wowing audiences with her masterful singing, recitations, and personal charm.3 Such wildly enthusiastic responses to their shows enabled Polish artists and Soviet audiences to transcend sharp national antagonisms, at least momentarily. Admiration between Polish and Soviet entertainers was often mutual. Writing about the Russian artists whom he met on tour during this period, Kazimierz Krukowski praises such popular singers as Klavdia Shulzhenko and Mark Bernes and senses the comic potential of a young Arkady Raikin, the brilliant satirist who flourished on the postwar Soviet stage.4

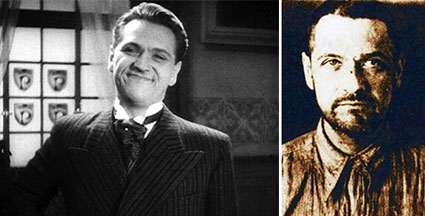

Eugeniusz Bodo: Publicity still, and a photo from the gulag.

To be sure, Polish performers who toured the Soviet Union between 1939 and 1941 were not threatened with mass execution or labor in the worst Gulag camps, as were certain targeted groups among the deportees. The Stalinist government aimed to liquidate Poland’s political leaders and high-ranking military officers, not their popular entertainers. Yet there were occasional instances when Polish artists unwittingly made themselves enemies of the Soviet people, usually when they tried to head west. Ordonka was retreating to Wilno (now Vilnius) when the secret police sentenced her to work on a pig farm near Kuibyshev; the post-invasion amnesty saved her life. Eugeniusz Bodo’s repression was the most shocking. His enormous musical talent and excellent Russian would have ensured him Soviet stardom indefinitely had he not made up his mind to emigrate to the United States in 1941. The impetuous Bodo was arrested and sent to a labor camp near Arkhangelsk, where he perished from hunger and overwork.5 Juxtaposed photos of Bodo the star and Bodo the prisoner mark his deadly passage from ebullience to exhaustion. In contrast, Wars, Bodo’s more levelheaded friend, worked his ties with famous Soviet composers to extricate his wife and son from the Warsaw Ghetto before the Soviet-German alliance fell apart. The fates of Bodo and the Wars family illustrate the double-edge in Polish-Soviet relations during the first three years of the war: the Stalinist government murdered tens of thousands of Polish citizens to advance their imperial agenda, but sometimes offered others a very basic refuge from Nazi annihilation.

By autumn 1941 Warsaw’s refugee artists were suffering as much as their deported compatriots, battling hunger, cold, disease, and exhaustion from nonstop travel in freezing, lice-infested cattle cars. Like hundreds of thousands of forcibly uprooted Polish citizens, they longed to go home. That these entertainers steered a course for the II Corps recruiting centers underscored their patriotism, their overwhelming preference to serve Poland rather than the Soviet Union once such service was possible. These performers may have formed friendships with Soviet artists and had been embraced enthusiastically by Soviet audiences, but they showed absolutely no desire to settle down as Soviet citizens.

More intriguing is the fact that Anders and his staff sought them out for service. The Corps surely did not need more mouths to feed. Former soldiers, historians, and one of the first rabbis attached to the Corps attest to anti-Semitic attitudes held by many officers, especially evident in their preferential admission and treatment of Christian over Jewish recruits. Perhaps the Corps invited acculturated Jewish entertainers to join up in much the same way that they accepted acculturated Jewish medical officers. An estimated 60% of the Corps’ doctors were identified as Jews.6 The professional skills of Jewish artists and doctors were well-established in the worldview of most Polish Catholics, whereas the notion of a Jewish warrior struck quite a few career officers as an improbability, despite the commendable service of Jewish soldiers in many past Polish campaigns.

It is most likely, however, that these star-studded troupes formed a class by themselves in which religious identity was beside the point. They awed everyone in the Anders Army as the best in show business, as charismatic national celebrities who would add luster to the Corps’ daily life and worldly reputation. After all, even when the numerus clausus (quotas) severely restricted the admission of Jewish students into Polish medical schools in the 1930s, politicians and career officers still hobnobbed with the capital’s famous artists. Krukowski implies a familiarity of equals when he writes of “the collegial meeting, filled with reminiscences of Warsaw,” between himself, Konrad Tom, and General Anders in Buzuluk in October 1941.7 The experienced cabaret impresario quickly guessed that these in-house entertainers would serve in part as a “court theater” for VIPs and the top brass of the Corps. Once the II Corps and its attached civilians were evacuated from the Soviet Union in spring 1942, its two theater units, directed respectively by Krukowski and Konarski, entertained kings, shahs, and generals throughout the Mid-East and Europe.

It is most likely, however, that these star-studded troupes formed a class by themselves in which religious identity was beside the point. They awed everyone in the Anders Army as the best in show business, as charismatic national celebrities who would add luster to the Corps’ daily life and worldly reputation. After all, even when the numerus clausus (quotas) severely restricted the admission of Jewish students into Polish medical schools in the 1930s, politicians and career officers still hobnobbed with the capital’s famous artists. Krukowski implies a familiarity of equals when he writes of “the collegial meeting, filled with reminiscences of Warsaw,” between himself, Konrad Tom, and General Anders in Buzuluk in October 1941.7 The experienced cabaret impresario quickly guessed that these in-house entertainers would serve in part as a “court theater” for VIPs and the top brass of the Corps. Once the II Corps and its attached civilians were evacuated from the Soviet Union in spring 1942, its two theater units, directed respectively by Krukowski and Konarski, entertained kings, shahs, and generals throughout the Mid-East and Europe.

Feliks Konarski performs at Monte Cassino

Whoever was responsible for importing and embedding these stars in the Corps had made an excellent investment on two counts, ensuring the Corps’ good relations with its host countries and allies and buoying up its huge, slowly advancing army/diaspora. Warsaw’s popular performers were fluent in the global languages of swing music and modern comedy. They embodied and advertised national prowess. While cabaret and revue artists did not present classic Polish culture, their performances, complete with nostalgic songs of the city and stylized folk dances, were hailed as high-quality, popular, educational entertainment – entertainment that foregrounded a cosmopolitan nation and beautified images of its rural and traditional past. Krukowski’s comic sketches, Konarski’s sentimental songs, Wars’s deft compositions, and the excellent music making of Terné, Bogdańska, Borucki, the Tea Jazz Orchestra and others thrilled and cultivated their soldier audiences. When the cabaret went to war, it transformed the rank and file of the Polish II Corps into eager consumers of big city culture, the fans of a fashionably modern Poland and aspiring citizens of the world.

CR

- Henryk Gold’s brother Artur, also a composer and a conductor, remained in Warsaw, was forced into the Ghetto, and was killed at the Treblinka death camp. ↩

- Anna Mieszkowska, Była sobie piosenka: gwiazdy kabaretu I emigracyjnej Melpomeny (2006): 197-98. ↩

- Mieszkowska, 63. ↩

- Kazimierz Krukowski, Z Melpomeną na emigracyj (1987): 29. ↩

- Ryszard Wołański, Już nie zapomnisz mnie: Opowieść o Henryku Warsie (2010): 126-7, 131. ↩

- Harvey Sarner, General Anders and the Soldiers of the Second Polish Corps (1997): 143. ↩

- Krukowski, 33. ↩

Pingback: Welcome to our 2014 Fall-Winter Issue!

Great piece!

Thanks for a great “first taste” of the upcoming book – filled with discoveries. Gen. Anders’ Army saved the lives of my mother’s cousins: the parents died of hunger, the children made it to the gathering places, and went, with the Red Cross as war orphans to Iran, Switzerland, and Chicago. Some of the musicians’ survival stories are very poignant – band leader Henryk Gold made it to America with the Anders’ Army, while his brother violinist and composer Artur Gold died in Treblinka.

TO BETH HOLMGREN

My father Bernard Siegel is in these band photos playing the guitar. I would like to get hold of a copy of the photo and any information you can send me about the Polish Parade band/orchestra around that time.

I was delighted to find these photos !!!

Helen Austin nee Siegel

Pingback: Trail of Hope: The Anders Army, an Odyssey Across Three Continents