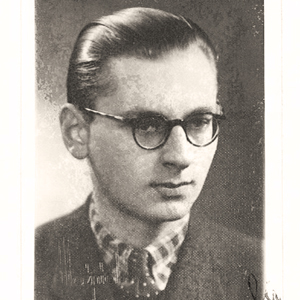

A young Władysław Bartoszewski in 1940.

Władysław Bartoszewski was about to begin his studies at university when the war started and interrupted his plans. In September of 1939, instead of beginning his classes he instead turned his attention to building barricades and taking part in the civil defense of Warsaw.

Soon after the German occupation began, the 18-year old Bartoszewski worked in the Polish social services department and for the Polish Red Cross – both crucial in the new conditions – but this work was also interrupted. In September 1940, he was caught in a random roundup in the leafy Warsaw suburb of Żoliborz and sent to Auschwitz, where he was prisoner #4427. Seven months later, protests from the International Red Cross in Geneva reached the German Red Cross in Berlin demanding the release of a Red Cross employee. The Germans had no choice but to do so.

On returning to Warsaw in April 1941, Bartoszewski remarked “…by that time I was equipped with the necessary experience and understanding of what was going on.” He reported on conditions in Auschwitz to the resistance organization, ZWZ, a precursor to the Home Army (AK), and resumed his studies at the clandestine University of Warsaw.

The Auschwitz experience strengthened his resolve, and he soon formally joined the clandestine Home Army (AK) working for the Bureau of Information and Propaganda (BIP). Jan Karski, at that time known only by his codename, “Franek,” introduced Bartoszewski to Zofia Kossak, a much-loved model of courage and patriotism who was constantly changing her codename, but to the young she was always just Ciocia (Auntie). By the end of 1942 he joined the secret Council for Aid to Jews, code-named Żegota, co-founded by Kossak, liaising with the Jewish members and heading the courier section, a network of mostly young women who delivered the funds and documents essential for the survival of hidden Jews.

All this time, he was also attending his secret university classes until once again his education was interrupted, this time by the Warsaw Uprising when he was engaged in editing news from the beleaguered city for radio and a newsletter. After capitulation, he escaped from the city, made his way to Kraków, and continued to work for the AK. He returned to the ruins of Warsaw in July 1945.

After the war, he made no secret of his activities in the AK despite the repression of AK members by the Communist regime, and testified before the Commission for the Investigation of German Crimes including reports about prisons, concentration camps and the genocide of the Jews. At first, when some prewar opposition parties were still tolerated, he joined the Polish Socialist Party and, since he continued being in touch with his AK and Żegota colleagues, he was a founding member of an organization called Human Rights, for the purpose of starting an educational campaign to offset the demoralizing effects of five years of war.

He was eager to return to his university studies but once again those plans came to an abrupt end in November 1946 when he was arrested by the security police. He was held in prison until April 1948 when he was finally released thanks to the efforts of a Żegota colleague, Zofia Rudnicka. In January of 1949 he was arrested again and held without trial until May 1952, when he was sentenced to eight years in prison by the infamous Stalinist prosecutor, Helena Wolinska.

In 1953, Stalin died, in 1954 Bartoszewski was released and in 1955 his alleged crimes dismissed, his arrest and sentence declared an error. He was 33 years old and it was time to resume his studies.

With Stalin’s death, the worst was over, but a free society was still a long way off. Bartoszewski was not accepted at the University of Warsaw until 1958 and then was expelled on the day he submitted his thesis. Completely erased from the student list.

That was his youth. But in the long term, the Communist regime could not defeat Bartoszewski. He went on to become a great historian and a prolific writer, and an indefatigable ambassador of peace and dialogue among nations.

He has lectured at universities in Poland, in Germany, in Israel and the United States, has received honorary doctorates, and awarded innumerable honours among them the Heinrich Brauns Prize presented by the Bishop of Essen, the Stresemen Gold Medal, the Grand Cross of Merit with Star from the Federal Republic of Germany, the Order of the White Eagle from President Wałęsa, and many Polish awards. He was awarded the Yad Vashem Medal and made an honorary citizen of Israel in 1991. In 1995 he addressed a joint session of the Bundestag and the Bunderat in Bonn.

A copy of Bartoszewski’s book,

given to this article’s author in Montreal in 1999.

But most of all, he is just a wonderful human being. In 1999 he visited Montreal where he gave a public lecture at McGill University and had a special meeting with the Polish Students Association of Montreal. He was warm, friendly, interesting, very inspiring and funny. Asked about providing false documents he said he had become quite proficient in forging them himself, “something to fall back on in case I need a change of career.” But he also freely admitted that fear was a constant companion.

He is an unapologetic patriot and loves his country’s people, the Poles and the Jews, and teaches them to overcome their prejudices. He has striven for reconciliation with people that have been more difficult to love, but peace and mutual respect make the effort essential.

If only he could live forever.

CR

Here’s some interesting photos of Bartoszewski:

http://www.judytapapp.com/bartoszewski.php

Pingback: Krystyna Wituska: Her Life and Literary Afterlife

Pingback: 2014: The Year of Anniversaries