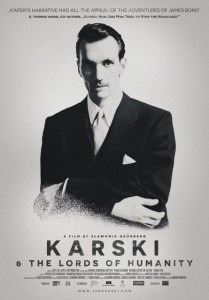

Karski and the Lords of Humanity

Karski and the Lords of Humanity

Directed by Sławomir Grünberg

Apple Film Productions, TVINDIE Film Production 2015

Speaking about Jan Karski, Holocaust historian Michael Berenbaum once said, “I’ve met Nobel Prize winners, but I truly felt I was in the presence of nobility when I was with him. He elevated every conversation.”

Rabbi Harold White described Karski as “a hero, a modern day prophet;” the highly respected British historian, Sir Martin Gilbert, spoke of him as an inspiration to young people. Honors flowed his way, including the posthumously awarded American Medal of Freedom.

Nevertheless, noted the Israeli newspaper, Haaretz, “somehow Karski’s commanding presence and death-defying mission to save Polish Jewry evaded Hollywood.”

Given Hollywood’s standards, perhaps it’s just as well. What could they do with a man who is noble and brave but modest, intelligent, honest, stoical, reserved, elegant and patriotic and still failed to provide a happy ending both for himself and for his cause?

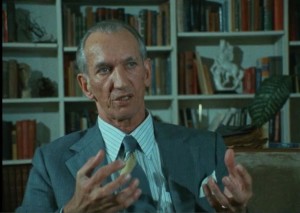

Polish-born director Sławomir Grünberg, addresses this challenge in his documentary, Karski and the Lords of Humanity, by making Jan Karski the star of the film, speaking for himself in hours of film taken by Wood when interviewing Karski for his book, and some film from Claude Lanzmann’s 1985 documentary, Shoah, capturing the tormented hero in what may well be the most dramatic interview ever filmed.

Jan Karski in a still from Shoah

Still, some visuals are needed and there must be a better word than “animation” for the stark and powerful images created by Grünberg’s artists under the direction of Tomasz Niedźwiedź. These dramatic images illuminate, but never distract, from the riveting story and are far from the usual animated figures or the trendy and simplistic comic book style that has recently become popular.

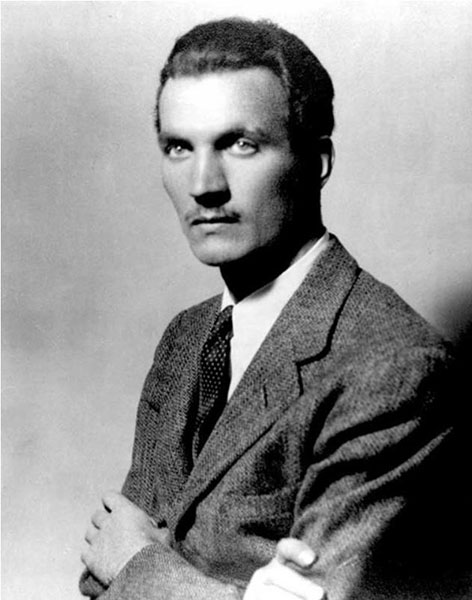

Grünberg’s portrait of Karski as a young man is excellent. He grew up in Łódź, a city he recalled fondly as lively and cosmopolitan. He speaks warmly of his mother, a devout Catholic who believed there was only one God, but people everywhere had their own interpretation of Him. He recalled that when he was at university in Lwów, Jewish students were sometimes bullied, and that some of his Catholic friends defended them. But he did not. Later he was ashamed of that, but at the time, he admits, he was too self-absorbed. And indeed, we see a very dashing, well-dressed young man mostly interested in his new diplomatic career and the perks that would go with it.

Young Karski at the start of his diplomatic career

The double German-Soviet invasion put an end to all that. Karski was arrested by the Soviets but escaped posing as an enlisted man and so evading the fate of the officers, all of whom the Soviets executed in the crime known as Katyń. He then joined the resistance at its earliest stage, before the various groups united to form the Home Army and the Delegatura, the military and civilian arms of the “Secret State” Karski later described in his book.

Disciplined, patriotic and appalled at the suffering in his country, he accepted all risks, all assignments including dangerous forays into occupied Europe. On one such trek he was captured by the Gestapo and tortured but then rescued by his Home Army compatriots. They were subsequently arrested and in reprisal the Gestapo executed 32 people. Karski never forgot that and bristled when he was singled out as a special hero.

After he recovered from the torture, Karski accepted his historic mission. Once again he would go across occupied Europe to deliver to his government—then in exile in London—documents from the underground authorities, and a special message from Jewish leaders about the genocide in progress. For this he was asked to enter the ghetto and a transit camp holding Jewish men, women and children for transport to death camps. Would he do this, and demand help from the leaders of the Western world? “Naturally I agreed,” he said, “on exactly the same basis as for all Polish political parties.” But what he saw “…was unprecedented. The Egyptian pharaohs never did this… nor the Babylonians… it was the first time in history…”

The film shows some footage of what Karski saw. One New York Times reviewer objected that showing the atrocities was not necessary but I disagree. Grünberg made the right decision. These were the atrocities that left an indelible mark on the young courier, and the guilt he always felt for failing to persuade western leaders to take action.

In London, Karski met first with his own government which published a report addressed to the governments of the United Nations titled “The Mass Extermination of Jews in German Occupied Poland.” The Polish Foreign Minister, Count Edward Raczyński, delivered a personal plea to the Pope.

He then met with Anthony Eden among others—Churchill was too busy—and although the British Parliament was moved to rise for two minutes of silence, nothing else was done. As Eden expressed it: How could they? What would people in other countries say? Why make Jews a priority? What would Stalin say?

In early 1943 Karski continued to America to meet with the most powerful leader of them all, Franklin D. Roosevelt, who listened politely for an hour. He met with, among others, Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter who said he could not believe him.

Roosevelt had told the young emissary: “Tell your people that they have a friend in the White House.” But the genocide continued, and in the end the friend gave Karski’s country to Stalin.

The young man who would some day be known as “Humanity’s Hero” failed to impress upon the Lords of Humanity the urgency of the Jewish tragedy. It is telling that he once said to Władysław Bartoszewski, an even younger compatriot in the Home Army, “At least you saved some Jews. I saved nobody.”

It is not for nothing that there is a touch of irony in the title, Karski and the Lords of Humanity, as in the scene of Karski imitating the aristocratic Roosevelt, cigarette holder in hand, saying those final words.

Artist’s depiction of FDR

The excellent screenplay is co-written by Grünberg, Katka Reszke, a filmmaker and writer on Polish-Jewish history, and E. Thomas Wood, co-author (with Stanisław M. Jankowski) of the solid biography, Karski: How One Man Tried to Stop the Holocaust.

Karski and the Lords of Humanity is an essential film for Holocaust and WWII studies, though perhaps disturbing for the very young. And it is simply an excellent film for thinking people everywhere.

CR

Pingback: Welcome to Spring 2016!

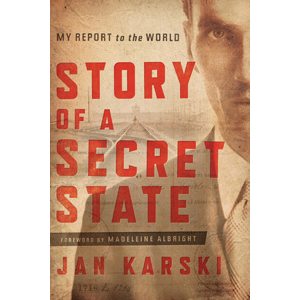

I have read STORY OF A SECRET STATE in addition to numerous articles about this peerless man. Kudos to Irene Tomaszewski, Slawomire Grunberg, and everyone involved in this site.

Pingback: Jan Karski, Humanity’s Hero, a Soldier of an Allied Army

A good write up. This nails something essential:

“Roosevelt had told the young emissary: “Tell your people that they have a friend in the White House.” But the genocide continued, and in the end the friend gave Karski’s country to Stalin.”