The Polish Underground and the Jews, 1939-1945

The Polish Underground and the Jews, 1939-1945

Joshua D. Zimmerman

Cambridge University Press

The Home Army – the largest resistance movement in occupied Europe with a decidedly non-Communist character that was the first to witness and respond to the Holocaust before genocide had a name – is certainly a subject in need of historical reckoning.

Historian Joshua D. Zimmerman’s book, The Polish Underground and the Jews, 1939-1945, proposes a framework from which to view the full range of actions of this complex underground movement in relation to the Jews. The Home Army’s flawed response to the destruction of the Jewish minority despite its anti-Nazi credentials has for too long paralyzed our understanding of the subject and eluded a satisfactory analysis.

As the author writes in his introduction, scholarship on the subject has been informed by “two mutually exclusive lines of interpretation” drawn along ethnic lines that have only been challenged in the last 25 years. The story of the Home Army suffered from the outset from propaganda issued by the Soviet-directed Polish Workers’ Party (PPR), in a campaign depicting the armed forces loyal to the London government-in-exile as “reactionary nationalists.” The portrayal of the Home Army as a “Nazi collaborator” gained an official imprimatur with the imposition of communist authority during Poland’s period of High Stalinism. In a linguistic reversal that might have put a wry smile on George Orwell’s face, the anti-Nazi pro-Western Home Army was identified as “fascist,” while the Soviet-backed communists claimed the status of the forces of “democracy” – Soviet-era views whose echoes can still be heard in pockets of today’s unreconstructed Left.

In the scholarship that emerged in the later postwar period, Polish historians either ignored the Holocaust altogether or characterized the reaction of the underground primarily in a benevolent light. Jewish historians, on the other hand, had a decidedly negative view of the Home Army. These views are best represented in a book co-authored by Israel Gutman and Shmuel Krakowski, Unequal Victims: Poles and Jews World War Two (1986). In Poland, the most authoritative historian on the subject is undoubtedly Dariusz Libionka, accessible so far only to Polish-language readers.

Because there has been no comprehensive study, some of the most esteemed western historians have fallen into the trope of describing the Home Army as solely “nationalist” in character. For example, in The Third Reich at War (2010), Richard Evans describes the Home Army as a “Polish nationalist resistance,” while in Remembering Survival: Inside A Nazi Slave-labor Camp (2010) Christopher Browning similarly labels it a “conservative nationalist movement.” One of Zimmerman’s core contentions throughout the book is that it is impossible to apply such a narrow label, as the Home Army (numbering 350,000 members by June 1944) was fundamentally a non-party “umbrella organization representing Polish society as a whole, including socialists, liberals, peasants, and nationalists” – and it is precisely this diversity that explains the remarkable variety of responses to Jews and the Holocaust. The author’s approach is to segment the subject into brief periods ushered in by the major political and military upheavals in a rapidly changing landscape. This calibrated examination is a major strength of the book.

If we simplify Zimmerman’s painstaking narrative for the purpose of the review, the dynamic between the Polish Underground and the Jews was conditioned by three tectonic shifts on the military and political landscape. The first of these was the German-Soviet occupation, which did the most long-term damage by giving rise to a widespread perception among segments of Polish society of Jewish collaboration in the Soviet zone – the stereotype of Judeo-Communism (Żydokomuna) – which played a crucial role in subsequent developments. Zimmerman does not debate the veracity of its underlying claims, but records with detachment its deleterious effects.

The fateful triangle of Poles, Jews, and Soviets then experienced a second tectonic shift in December 1941-July 1942. At this time, the first Soviet military victory against the Germans took place outside of Moscow in December 1941. These changing political winds gave rise to the formation of a rival communist underground in January 1942 – the Polish Workers’ Party (PPR) – loyal to Moscow. As Zimmerman notes, this “had the effect of exposing Jews to new accusations of pro-communist leanings” and “raised questions about Jewish loyalties.” The creation of the PPR led the Home Army, in turn, to establish a new division dedicated to anti-communist propaganda, later called Antyk. And the more radical activists within its ranks were unafraid to instrumentalize anti-Jewish feelings: “Antisemitism is still a useful weapon in the struggle against communism,” one of its reports stated.

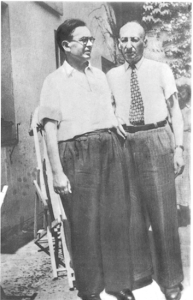

Henryk Woliński (left). Head of the AK’s Jewish Affairs Bureau and liaison with the Warsaw Ghetto leadership, with his Polish-Jewish friend Władysław Winawer (whom he rescued)

These developments from the east rubbed against a radicalization of anti-Jewish policy from Nazi Germany. The Wannsee Conference took place on January 20, 1942 and the death camps of Bełżec (March 1942), Sobibór (May 1942), and Treblinka (July 1942) began to appear on the horizon. The underground observed in horror and disbelief the “unprecedented terror against the Jews,” in its words, as Nazi Germany crossed a historical threshold in the implementation of industrial mass murder using poison gas. Yet, as Zimmerman points out, whatever the fluctuations in Polish-Jewish relations, detailed and systematic reporting of the unfolding genocide to the government-in-exile continued unabated. In fact, readers may be surprised to learn of the numerous BBC broadcasts in the free world and newspaper pages dedicated to publicizing the Holocaust in the Daily Boston Globe, The New York Times, and The Times of London. At this time, the Home Army also became more responsive to the Jewish community by creating a Jewish Affairs Bureau in February 1942 headed by Henryk Woliński, one of the chief protagonists in Zimmerman’s narrative, who would come to play a key role in the establishment of a section of the underground called the Council for Aid to the Jews (codename Żegota) in December 1942. The precarious balance of Polish-Jewish relations was caught within these moving parts.

The third period introduced a new set of dilemmas with the massive wave of “liquidation actions” that swept across the ghettos of the General Government, described by the Bund representative Leon Feiner as “a downright elemental storm.” This situation gave rise to a number of developments from the summer of 1942 up to the time of the Warsaw Uprising in August 1944. The unhinged German violence and increasing reports of trains heading for death camps broke a psychological barrier among segments of the Jewish community that might have entertained any illusions about work “in the East.” This had two important consequences for Polish-Jewish relations. First, a younger generation of Jews, particularly in the Warsaw ghetto, started to form an armed resistance movement, which began sending out feelers to the Home Army, to which Gen. Stefan Rowecki initially responded with a lack of confidence in the ability of Jews to fight and offered very limited support. This has often been taken as proof of an official line in which “moral obligation” was increasingly extended to ethnic Poles only. Zimmerman accepts this, but is more sympathetic to Rowecki, arguing that – given the absence of Jewish armed resistance to date in the Warsaw ghetto and the limited arsenal of weapons that was being saved for a general uprising – the general’s position made sense in that particular historical moment. He points out that as soon as the January 1943 revolt showed success, interrupting deportations to Treblinka, Rowecki immediately reversed his policy and offered more help, though not without internal opposition.

Józef Pszenny, deputy chief of the Warsaw District Home Army, commanded the unit that attempted to blow up the ghetto wall on the first day of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

The Home Army’s reaction to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising launched on April 19, 1943 has been one of the most contentious issues in Polish-Jewish history. Zimmerman is careful to remind readers that the background to the tragic Jewish struggle for “death with honor” was a national and diplomatic crisis following the discovery of a mass grave of Polish officers in Katyń, just six days prior to the uprising, which led Stalin to break off diplomatic relations with the London-based government. The author draws attention to two failed attempts, led by Capt. Józef Pszenny – one of the first armed actions of the Home Army – to blow up a section of the ghetto wall, which would allow Jews to flee, followed by seven documented “solidarity actions” by other units against German and Ukrainian auxiliary forces guarding the ghetto walls.

The second major Jewish response to the ghetto “liquidations” was a massive escape from ghettos – by some estimates, 10% of the population. The German occupation authorities responded to this by organizing hunts for Jews, or Judenjagd in German, which often co-opted locals. This dire situation was compounded by increased fighting between the Home Army and pro-Soviet partisan groups, which grew in confidence after Soviet victory at Stalingrad in January-February 1943. The failure of the Polish Underground to develop an adequate policy of dealing with fugitive Jews left them at the mercy of local partisan dynamics and coordinated German “hunts”. This failure was partly a function of a change in leadership after the capture of Gen. Rowecki by the Gestapo and the death of Commander-in-Chief, Władysław Sikorski, in the summer of 1943, shifting the policy from one of relative sympathy to hostility toward Jews under Gen. Komorowski, a sympathizer of the antisemitic National Party.

Jewish platoon of the AK in the Hanaczów, Lwów (Lviv) district (c. January 1944) under the command of Home Army Lt. Kazimierz Wojtowicz. The platoon was led by Bunio Tenenbaum

Zimmerman dedicates a chapter that deals specifically with documented cases of Home Army units that participated in the killing of Jews. He introduces a convincing distinction in trying to understand this violence, much of which still remains shrouded in mystery. He argues that in northeastern Poland (Lublin, Białystok, Nowogródek, and Wilno), where fighting with Soviet partisans was much higher, the Home Army “increasingly identified local Jews as hostile, pro-Soviet elements” or “Bolshevik-Jewish bands.” It is in these areas that anti-Jewish actions can be traced to the district command. By contrast, cases examined in central Poland (Kielce, Radom) show that violence toward Jews, often tied to robbery, was initiated by local command without approval on the district level. The local command spectrum also includes the extraordinary story of a Jewish platoon under the command of Lt. Kazimierz Wojtowicz in the village of Hanaczów (Lwów district), that protected some 250 Jews.

This is a compelling way to approach a period of the occupation in which increased partisan warfare overlapped with the Judenjagd. However, the danger of dealing too narrowly with cases that pertain solely to anti-Jewish violence runs the risk of analytically thinning out the explanatory framework. Here, the author might have benefitted from historian Marcin Zaremba’s Wielka Trwoga. Polska 1944-1947: Ludowa reakcja na kryzys (2012), which includes an important chapter on the social aspects of banditry or what he calls the “Peasant War of Fallen Soldiers.” The picture that emerges in Zaremba’s book is of a dramatic collapse of social norms in the countryside, with the underground state fighting not only collaborators, but its own society to prevent its slide into a moral abyss. No memoir better depicts the moral transformation of members of the Home Army with such ruthless honesty as Stefan Dąmbski’s Egzekutor (2010), who joined an AK unit at the age of 16 and quickly became an effective executioner on behalf of underground tribunals. An examination of the underground justice system might better contextualize ethnic violence with broader patterns of social disintegration. In this light, there is reason to believe that the social reality of war at the local level can provide a competing framework for anti-Jewish violence.

Other questions still require in-depth study and will need to be tested against Zimmerman’s interpretation. One issue concerns the mutual perceptions between Jews in ghettos and the underground. A number of Home Army reports reveal a suspicion of Jewish Councils and their relationship with the Gestapo. Another topic is the complex situation of the Polish “Blue” Polish, many of whom served a dangerous and vital double role as members of the Home Army. There is also the thorny subject of networks of Jewish informers in the service of the Gestapo, especially in the Kraków region, and their impact on perceptions.

Jadwiga Deneko, courier for the Children’s Section of Żegota. Arrested in November 1943 while sheltering 13 Jewish children in Warsaw, executed by firing squad in Warsaw on January 8, 1944 in the Pawiak Prison

Yet these observations in no way take away from the author’s accomplishment. The underground resistance movement that produced noble figures such as Jadwiga Deneko of the Children’s Section of Żegota, but also coexisted with armed units that killed Jews like that of Marian Sołtysiak “Barabasz,” has puzzled historians for decades. Zimmerman’s framing offers the first comprehensive attempt at synthesizing these seemingly contradictory phenomena. The author has dealt with a subject that seduces us into moral judgments despite our best intentions. Zimmerman does not lose sight of the crucial crises and dilemmas that informed each historic moment and thus carries out two fundamental tasks of the historian: restoring the buried sense of historical contingency and recognizing the human proportion of experiences still painfully fresh.

![]()

Pingback: Welcome to Winter 2016!

Thank You, but why no words about Witold Pilecki, Jan Karski, Szymon Zygielbojm, Maria Kossak-Szczucka, Irena Sendler? Captain Rotmistrz Pilecki volunteered for a Polish resistance operation to get imprisoned in the German Nazi Auschwitz death camp, as early as 1941 informed Sweden, USA and UK of Germany’s atrocities. He escaped from the camp in 1943 after nearly two and a half years of imprisonment. (Vitold’s Report) Jan Karski was in the camp too, and informed the Western Allies of Nazi Germany’s Auschwitz atrocities. (Karski’s Report).

My commentair was wrong, bacause I wrote about captain Witold Pilecki, Jan Karski, Irena Sendler or Zofia Kossak-Szczucka? Bacause I wrote about Vitold’s Reports, Karski’s Reports?

Yet another Jewish-wrongdoing-denialism book. Brings nothing new, copies standard accusations towards Poles. According to Zimmerman Jews did not play any role in Polish-Jewish antagonisms. Blames the Narodowa Demokracja for Jews wanting to emigrate to Palestine. Does not tell that most Jews did not want to be part of Polish nation. The author consistently tells half the story: Jewish half. This book is huge waste of time.