Pahiatua, NZ: A girls basketball team; 1948

PHOTO courtesy of the Kresy-Siberia Virtual Museum

Exhibition: Daily Life

It was almost two years ago while I was in Australia that an intriguing event presented itself on my Facebook newsfeed. It was a gathering of Polish New Zealanders, a community with a history that calls for particular celebration as well as recognition of the country that gave them refuge. Since my current research includes human migration, with special attention to child refugees, I have been interested in this community since I first learned of their unique story. Soon enough I was headed for Wellington; the city that in 1944 welcomed over 730 “Pahiatua Children,” the country’s first invited refugees.

Welcomed is an understatement. This short documentary from New Zealand on Screen tells the story of the children’s tragic experiences in the Soviet Union, and follows them as they settled and grew up in New Zealand.

Pahiatua, NZ: Girls class

PHOTO courtesy of the Kresy-Siberia Virtual Museum

Exhibition: Daily Life

Pretty impressive. The first-hand accounts of these children’s experiences are further documented in New Zealand’s First Refugees: Pahiatua’s Polish Children, which have only deepened my interest in this truly unique experience.

As the children disembarked at the Wellington wharf, they were greeted by cheering crowds, heartfelt speeches, a band, cameras and a film crew. “Upon arrival in New Zealand, we were greeted by a huge crowd of people who were giving out small gifts,” recalls Ryszard. “As we were shepherded to the train for the journey to Pahiatua, someone in the crowd handed me some candy. As I recall, it was shaped in the form of small biscuits in different colours and tasted heavenly. This was my first taste of candy.”

Well-wishers thronged as they boarded the train set North for Pahiatua where a temporary home had been established for them. All along their journey, they were welcomed with friendly waves from small towns, from farms, and along country roads…

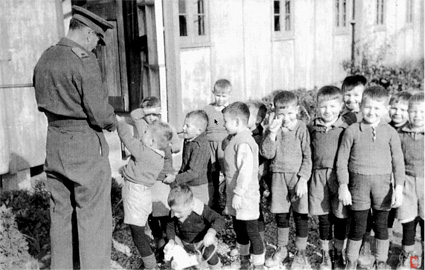

Pahiatua, NZ: The camp commandant, Major Foxley, shows the kindergarteners a “disappearing sixpence” trick.

PHOTO courtesy of the Kresy-Siberia Virtual Museum

Exhibition: Daily Life

Regina remembers the train journey from Wellington to the Polish Children’s Camp in Pahiatua. “At all the stops we were greeted by people and school children waving New Zealand and Polish flags and banners. They gave us ice cream and small change. We saw beautiful colourful houses on hills, so different to those in Iran. And in Pahiatua we had a great reception, with the army band playing and photos taken with smiling, friendly people. Happiness was everywhere and we felt very welcome.” How often do we see local people coming out to wave and welcome refugees?

Pahiatua, NZ: Girls at the river, behind the camp.

PHOTO courtesy of the Kresy-Siberia Virtual Museum

Exhibition: Daily Life

This hospitality lasted well beyond the “Welcome Day.” The Children’s Camp in Pahiatua provided the necessary environment for healing. Ryszard reminisces that “to a young kid [it] was a paradise. We made our own toys and our surroundings were a magic land – a river, native bush and the surrounding farms which we raided for turnips and were often chased away by the farmers.”

The children were well cared for, were invited to perform their traditional folk dances, plays, and songs, and were invited to stay in the homes of families from across the country during the holidays. Ryszard continues that “on our holidays, we were billeted out to New Zealand families and I was sent to a farm. The experience was unforgettable – animals, orchards and the general smell of the farm. The farmer was very kind, and he took me and Jan Lepionka to the town in his car and bought us ice creams in a cone. I thought I was in heaven. The farm was such a fun place.”

Pahiatua, NZ: A scooter in the camp.

PHOTO courtesy of the Kresy-Siberia Virtual Museum

Exhibition: Daily Life

As a researcher interested in the factors that contribute to the well-being of refugees and immigrants, I had never come across a host country offering such a warm celebration and reception in their host country. These Polish children went through many distressing experiences that included war, exile, migration, uncertainty, and loss of their family members. And yet overall they seemed happy, and they contributed significantly to both New Zealand society and culture. Such a welcome – from the government and the people of New Zealand – has not likely ever been matched anywhere. Today, the Poles of New Zealand have a thriving community, which includes the Polish Heritage Trust Museum of Auckland (I learned that every year they host Polish Easter Egg Decorating Lessons, which sell out to Poles and non-Poles alike!), various dance ensembles, educational organizations, and social clubs, as well as recently marking the 70th anniversary of the arrival of the Pahiatua Children, which was recognized in conjunction with the “Celebrating Everything Polish” festival in Wellington.

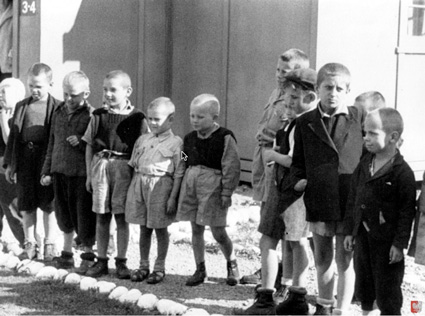

Pahiatua, NZ: A group of the younger boys watch the gardener (not pictured) cut grass with a lawnmower; they’d never seen such a contraption before.

PHOTO courtesy of the Kresy-Siberia Virtual Museum

Exhibition: Daily Life

The visit to New Zealand left me thoroughly inspired!

Why is it important to understand the welcome practices of host countries, the treatment of child refugees, and the long-term well-being and adaptation of both child refugees and their communities? Childhood trauma and distress is associated with a variety of negative outcomes and post-traumatic stress (PTS), especially among orphans. Sometimes post-traumatic growth (PTG) takes place instead. PTG occurs when one’s struggles with traumatic events act as catalysts for positive growth that may change one’s perception of self, relationships with others, and philosophy of life. External factors that can be manipulated may affect one’s ability to cope, adapt, and experience PTG.

Pahiatua, NZ: And now some older boys try their hand at a mower.

PHOTO courtesy of the Kresy-Siberia Virtual Museum

Exhibition: Daily Life

We turned to the Pahiatua Children’s testimonials which allowed us to investigate: (1) What are the different dimensions of PTG that the Polish children experienced due to WWII and migrating to New Zealand? and (2) What were some of the conditions that encouraged PTG? Examining a sample of testimonials with a fine-toothed comb (through thematic content analysis), an interesting result appeared. More than any other dimension, most of the testimonials in the sample demonstrated “relating to others” as a form of PTG. This dimension reflects an interpersonal change that includes feeling closer to others, improvements in getting along with others, and a better understanding of others.

An example from the testimonials is this one, from Ryszard, who states: “I could hardly believe that strangers could be so kind. I think this restored my belief in humanity.”

Pahiatua, NZ: Dining Room No. 2; lunch on a Sunday; 1948.

PHOTO courtesy of the Kresy-Siberia Virtual Museum

Exhibition: Daily Life

Why is this important? One potential explanation for this finding is that these children were cared for and looked after exceptionally well when they were in New Zealand. These children were surrounded by a community of other Polish children and staff who would have been sources of social support and who would have instilled a sense of belonging. They were in a safe and playful environment while their basic needs were satisfied. One of the children, Irena, notes that “the effect of eating regular meals began to change my body, I began to want to run and jump with my friends. We started to play games and we started to laugh. I don’t think I had ever laughed before. The joy of simply being alive filled my whole body. It was lovely to be, to live and to experience. Life was worth living! Many spaces around the camp were used for games of hide and seek, daring jumps over huge puddles of water after the rain or negotiating the nearby river […] In Pahiatua, I came to appreciate the features of the country – its lush green landscape. Life in New Zealand for me had magic about it and a quality of excitement that I had never experienced before.”

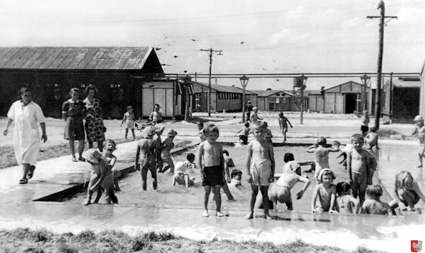

Pahiatua, NZ: The kindergartners in the camp’s pool.

PHOTO courtesy of the Kresy-Siberia Virtual Museum

Exhibition: Daily Life

In addition, New Zealanders and their government provided resources, care – and sincere acceptance – to children living with the trauma of war and displacement. Doing so may have eased the children’s adjustment to a foreign country and also helped them to see the good in people. Thus, for these children, rather than migration to New Zealand having been construed as yet another negative experience, stressor, or setback, it may have been perceived as an opportunity that offered them a chance to build a new life. Irena further reflects that “as I look back on the planning and thought that the New Zealand authorities put into our reception, housing and programme of recovery for us at the camp, I am profoundly thankful for the wonderful welcome and recovery programme that enabled us to begin a new life in this country.” While it may not have been experienced in such an idyllic way for everyone (and further work is needed to fully understand the diversity of experiences), her reflections strongly resonate with most of the testimonials.

Pahiatua, NZ: Girls skip rope in the warm Pahiatua sun.

PHOTO courtesy of the Kresy-Siberia Virtual Museum

Exhibition: Daily Life

While there is a uniqueness to their story and experience, there is also an important common and relevant thread to be understood. Childhood migration is not uncommon today. In recent years, increasing attention has been placed on the treatment of children who are asylum seekers, refugees, and immigrants during their various stages of migration. Following the traumas that they experience, do we want to encourage stress, or facilitate growth? “Even today, when the stresses of life get too much,” Ryszard confides, “I transport myself mentally […] and this helps me to handle life.”

In 2015, we still have a lot to learn from the example of New Zealand’s treatment of the Polish Children of Pahiatua. The “temporary” refuge offered by New Zealand turned out to be permanent. The refugee children grew up to be happy, solid citizens with an enduring love for their adopted country.

CR

Pingback: The Indomitable Spirit of Halina Babinska: A Very Special Coming of Age Story

Pingback: Welcome to our Spring 2015 issue!

Great article, great Kiwi spirit! Please visit the online exhibition about the Polish Refugees in New Zealand (1944-1951) in the Kresy-Siberia Virtual Museum http://kresy-siberia.org/newzealand/

Great article! Always love hearing about your research, keep it up!

Thank you for the positive feedback, support, and so many Facebook likes!

I definitely highly encourage everyone to check out the online exhibition about the Polish Refugees in New Zealand (1944-1951) in the Kresy-Siberia Virtual Museum http://kresy-siberia.org/newzealand/

Paulina, hopefully there will be some more forthcoming articles related to my research 😉

Thanks for your article, Amanda. Your readers might also like to see my father-in-law’s book,”A New Tomorrow: the story of a Polish-Kiwi family”, which traces his life from witnessing the German invasion of Poland in September 1939, through to Soviet labour camps, then an arduous journey to Persia, then on to New Zealand, arriving in November 1944. Link: http://www.amazon.com/dp/B00NGHUWB6

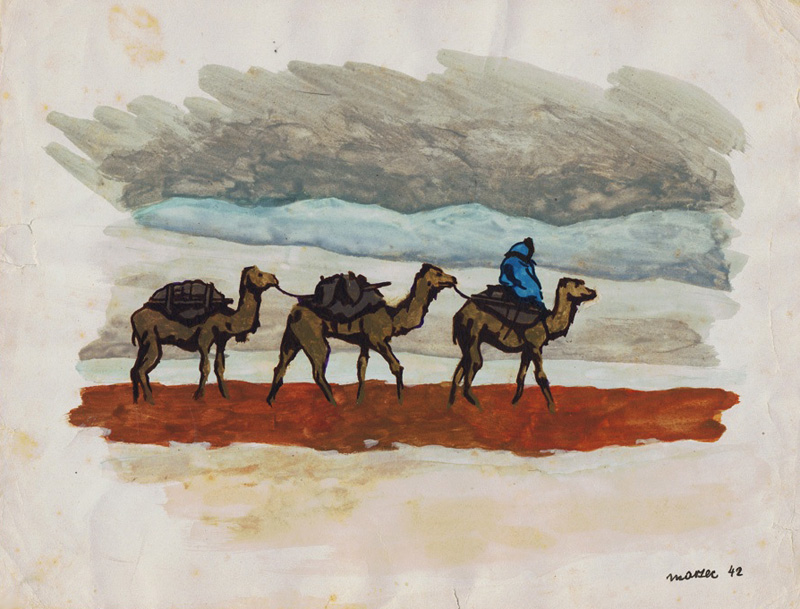

Pingback: The Africa Connection