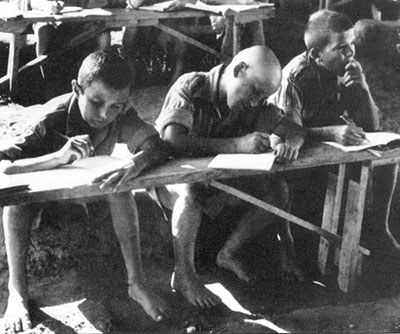

School in Masindi.

“We’ve come to this! They brought us here to get rid of us. They removed us from civilization so no one will know, no one will hear us. For the rest of our lives!”

These may well have been the understandable feelings of the Poles who had been taken from their homes and deported to the forests of northern Russia in 1940, but these words were spoken by the first Polish arrivals in Masindi, Uganda, in 1942. They were, in fact, the same people: Poles who had been deported to Siberia by the Soviets in 1940 and who managed to escape with the army of General Anders in 1942.

From the Arctic to the Equator in just over two years, an incredible journey and an astonishing story of resilience, stoicism and spunk.

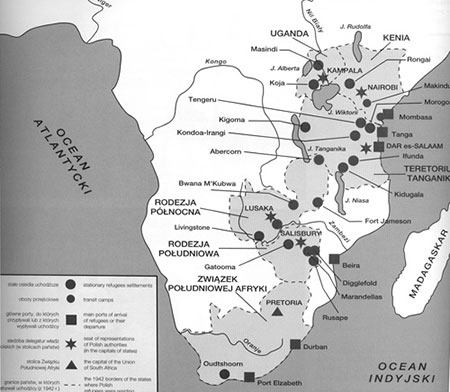

Polish settlements in Africa.

Their odyssey was beyond anything they could ever have imagined, travelling by trains, river barges, trucks and carts from the arctic regions of Russia, to the steppes of Siberia, the deserts of Kazakhstan, some of the bleakest regions of Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan and across the Caspian Sea. In Persia, their journey continued in convoys of trucks on narrow, serpentine roads over mountains, sometimes across bamboo bridges, and then more deserts to the Persian Gulf coast or by train to India. From there they would be dispersed once again… but where to?

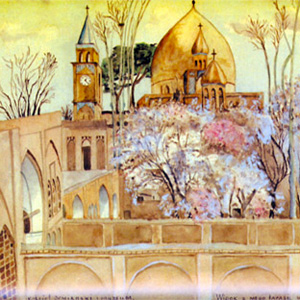

They were refugees, former prisoners from Stalin’s gulag, risking any kind of transport to get away from that monstrous land. When they reached Iran – though back then it was known by its ancient name, Persia – the healing began, both physical and spiritual. Some, who had crossed overland from Tashkent, were hosted overnight at a Persian orphanage, treated not only to chicken, rice, fruit and sweets but also to songs and dances performed by the Persian children. Someone who landed on the shores of the Caspian at Pahlavi told another story. “I remember,” she said, “seeing people dressed in colourful clothes carrying baskets. Suddenly they began throwing things at us. It was frightening; we thought they were stones, but they were pomegranates!”

India was magical, a sea of brilliant colourful clothes, smiling faces, and very spicy food. “Monkeys were everywhere, it seemed, and if we weren’t careful, they would take food right out of our hands.” After a while, it did not seem strange to see an elephant serenely transporting several riders. “No adventure stories we ever read as children prepared us for this amazing country.”

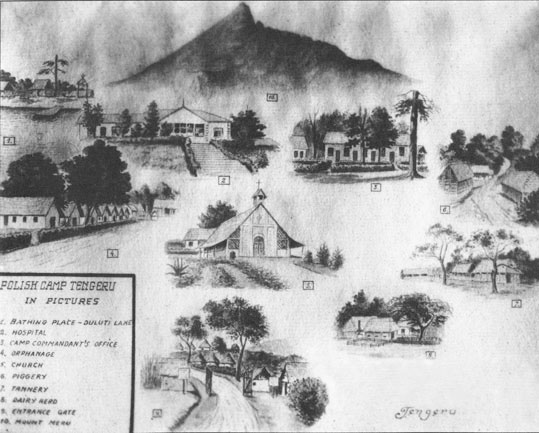

TENGERU POLISH CAMP IN PICTURES:

1. Bathing Place – Duluti Lake 2. Hospital 3. Camp Commandant’s Office 4. Orphanage 5. Church 6. Piggery 7. Tannery 8. Dairy Herd 9. Entrance Gate 10. Mount Menu

Along the way, the long line of refugees from the USSR was dispersed in different directions. Some 1,000 orphans accompanied by a few guardians went to the beautiful city of Isfahan in central Iran; another thousand were taken in by the Maharaja Jam Saheb Digvijay Sinhi; about five thousand were given a safe haven in Valivade in the princely state of Kolhapur. There were thousands more, and finding a safe haven in a world at war was not easy. But Britain still had colonies in Africa, and it was decided that 32,000 would go there to wait out the war in hastily built refugee settlements. And they were settlements, though frequently referred to as “refugee camps.” Words are important and this distinction likely contributed to the sense of dignity of all “Polish Africans” and to the joyful memories of the children, whether they were aware of the term, or not.

Crossing the Indian Ocean was a dangerous undertaking during the war. German and Japanese submarines were everywhere and transports could only be undertaken in convoys. But whatever anxieties the mothers may have felt, for the children it was a great adventure with flying fish, playful dolphins and gigantic waves. And on to Africa, to trains awaiting them in Mombasa. The first group of refugees would go on to Masindi, in Uganda.

At the source of the Nile.

Masindi is situated near the source of the Nile, not far from Murchison Falls, a beautiful area surrounded by volcanoes that boasted 273 earthquakes in one year, though none of them very severe. Home to so many magnificent wild creatures, including the world’s largest crocodiles, it was a dream laboratory for any zoologist. But for a few hundred exhausted women and children, it was a frightening reality. At first. But a few years later, one of them was to say, “Were it not for the longing for home, this is where we would want to live.”

Not much was ready for this first group, though it included 311 school age children, but eventually it would comprise six “villages,” one of them with 438 people of whom only 13 were men. The over-all director of the settlement was an architect who had built the Polish Pavilion for the World Fair in New York in 1938.

Visiting a mission school.

The author is wearing a pith helmet.

Among the first arrivals was Dr. Jadwiga Zielinska who set up Masindi’s hospital, which would ultimately have 40 beds, three doctors, 27 nurses and a pharmacologist. In 1942, the settlers’ health was still not fully recovered and now Dr. Zielinska had to deal with malaria and other tropical diseases caused by parasites and insects. But first, one had to cut through three kilometres of elephant grass and clear 50 hectares, and also get over their shock and stop the lamentations. Fearful mothers made children fearful so the mothers did what had to be done: concealed their fear, rolled up their sleeves and got to work. The children had to be fed and put to bed; the mosquito nets unnerved the mothers but quite enchanted the kids. With memories of howling wolves in the dark forests of Russia still a vivid memory, the Poles now had to convince themselves – and reassure the children – that the nocturnal choir of shrieks, howls and growls of the African animals was nothing to fear.

The first school.

School was under the direction of Dr. Kazimiera Skórska who also organized a theatre, puppet shows, and a newspaper. The first classrooms were set up in the shade of giant trees – one mahogany was two metres in diameter and over 30 metres tall. Desks were of very rudimentary construction and the children sat on stones or blocks of wood. At first teachers taught from memory, while the students were equipped with stubs of pencil and bits of paper. Eventually they received books, some from Polish Americans, some from England, others quickly printed by the army in the Middle East. But at first they used whatever came their way, including a Baptist Bible, frowned upon by a visiting priest but a treasure in Dr. Skórska’s view.

The settlers had much to do and soon discovered talents amongst them that included construction, carpentry, tailoring/dressmaking, shoemaking, hairdressing, bakery, electrical, water pumps, brickworks, ironworks, welding and woodworking.

Stopping for fast food: The author with her sisters, a friend and a guardian.

Nearby plantations grew a variety of crops including yams, corn, nuts, bananas, avocado and tapioca. The settlers learned to grow some of these too, but also planted old favourites, such as beans, tomatoes and potatoes. They grew. Sometimes their crops were trampled by elephants and rhinos, while monkeys and baboons liked to come for lunch, so the settlers had to share – but it was very entertaining.

A year later, there were over 3000 people living in Masindi, with a school population of 1,653 in elementary, gymnasium and lyceum levels. Everyone had a feeling of great satisfaction that they “could manage, no matter what.” So they built themselves a church.

An even larger settlement was established in Tanganyika, (now Tanzania). Tengeru would ultimately have a population of 5,000, again with a large orphanage. Situated at the foot of Mount Meru near the cool waters of Lake Duluti, one could always see Mount Kilimanjaro in the distance. There were banana forests nearby providing “fast food” for hikers, while their leaves served as umbrellas whether to shelter from sun or rain. They were also used to wrap meat at the butcher’s. The bamboo forests were like a cathedral, the tall trees its pillars, creating a green oasis that cooled the body, soothed the soul.

A Tengeru house. The street sign reads, Ul. Antokolska.

Tengeru was equally well organized, boasting a hospital, the three levels of school plus technical schools, and a church. A library, a YMCA, theatre, and a cinema (just a roof on stilts) were added attractions. Like Masindi and all the other settlements in Africa, their round huts soon had European gardens around them, with neat hedges and colourful flowers. The pathways of the settlements had street signs bearing the names of Polish poets, composers and historical figures.

The farm at Tengeru produced all the produce, milk and meat the community needed. Indeed, it was so successful that after the Polish refugees left it was taken over by the government of Tanzania and was the beginning of the Agricultural Research Centre.

The Tengeru Guides. Author’s sister is seated in the front row, on the left.

Throughout the settlements, all sorts of activities were made available to the youth. Scouts were a popular organization that created strong friendships, taught useful skills and provided many activities including trips. They also provided an opportunity to meet youth from other groups such as English, Hindu and African. That the Girl Guides and Boy Scouts were so popular could have a number of reasons. Certainly the quality and the dedication of the leaders was one factor but another was Africa itself. Unlike European Scouts, the African group did not have to look for “wilderness” areas they could go to a few weeks a year. The African environment was perfect – jungles, rivers, lakes, mountains, all of them pretty much uninhabited. The army sent some excellent leaders, among them the psychiatrist and educator, Dr. Victor Szyrynski who said, “I am convinced that our campsites and campfires in the tropical jungles ignited in the souls of these young people a sensation of pure beauty that will remain as a foundation for their lives.”

Mindful of the men and women serving with the Polish forces, the settlements organized handcraft exhibits and sales– tablecloths, napkins, bed linens, dolls, crocheted works. The sales were a big hit in the nearby towns and proved a successful fundraiser to help the people of occupied Warsaw and the men in German POW camps. The settlers also made sweaters, gloves, scarves, and leather goods such as wallets, and sent them to the POWs, along with razor blades that they received in large quantities from the US. Since there were so few men, they had little use for them.

The Masindi church in 2006. Photo courtesy of John Goddard.

To be sure, there were sad times. Children whose parents died in the Gulag had to learn to live with that ache in their hearts, but they formed strong bonds among themselves, creating surrogate families, and these bonds lasted to the present time. There was anxiety about their fathers and brothers fighting in Europe and their deaths were deeply felt. And there was the unknown future: Where? When? How?

Interior of the Masindi church in 2006. Photo courtesy of John Goddard.

The British authorities were, in general, helpful and supportive. But as always, there were exceptions. Some, at first, wanted to fence what they called the “camps,” only to be told that the Poles were citizens of an allied country and not prisoners. In Rhodesia, for example, a Lieut. Bakshaw snapped, “Why should the English taxpayer pay for you Poles?” The response was quick: “It’s not your king and your taxpayers paying. We’re paying with our blood and with our gold, that was smuggled out of Poland.” (i.e., the government-in-exile was footing the bill though indeed, the British provided the territory. Perhaps now it’s time to acknowledge that it was African territory.) When the war ended and Britain withdrew recognition from the Polish government in favour of Moscow’s regime, life became more difficult. But that’s another story.

Both Tengeru and Masindi, indeed all the settlements scattered around Africa, provided a few years of life touched by magic, a much needed healing after the brutality of the Soviet camps and then the unsettling disillusionment after the war, when the displaced Poles realized they could never go home, that their compatriot’s valiant war effort earned them only a betrayal. The most painful part was the separation of friends, and even families. Some were going to England, some to Canada, the US, Australia or Argentina. So they faced more wandering, but whatever challenges still to come, they knew they “could manage, no matter what.”

Both Tengeru and Masindi, indeed all the settlements scattered around Africa, provided a few years of life touched by magic, a much needed healing after the brutality of the Soviet camps and then the unsettling disillusionment after the war, when the displaced Poles realized they could never go home, that their compatriot’s valiant war effort earned them only a betrayal. The most painful part was the separation of friends, and even families. Some were going to England, some to Canada, the US, Australia or Argentina. So they faced more wandering, but whatever challenges still to come, they knew they “could manage, no matter what.”

CR

Pingback: Welcome to our 2014 Fall-Winter Issue!

Wonderful article about the strength of a people under extreme stress. I wish the ending was a better one but it was not to be. The finest revenge for all the suffering and betrayals is the resurgence of a free, independent, and growing Polish nation. Thank you for this and all you do to educate us.

Nice video about the Polish presence in Masindi: http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=YexPIfBYmz0

What a marvelous video, and how nice that Polish refugees are remembered so well. The feeling is mutual, as many former Masindi Poles would confirm. One note, though, is that the Polish settlers did not leave quite so abruptly as is said in the film, nor did their ship sink. However, quite a few have returned for a visit and a group in Toronto has funded and carried out a project for a new well to supply fresh water to the community. The church is still in use.

Great article! I wish it is read in Poland. The story is forgotten, or rather completely unnown.

We can’t forget those eight hundred children send to New Zealand where I had the honor

to listen to they stories(few of them)whale living there 30 years back.

Pingback: Chatting with Greg Archer

Pingback: The Indomitable Spirit of Halina Babinska: A Very Special Coming of Age Story

Pingback: February 1940: Exile, Odyssey, Redemption

Pingback: Bulletin Board Fall 2015

Pingback: The Africa Connection

I am Ludwik Smigielski, and was five years in Camp Lusaka N. Rhodesia now Zambia. From Feb 1943 to May 1948 with my mother Julia & sister Jozefa. We were exiled from our home in Olchowiec nr. Town of Brody, kresy, now Ukraine. I have my manuscript compiled years ago when both mother & sister were alive. I Lusaka I was eight to therteen years old. willing to share my story. I live in New Jersey USA. Ludwik Smigielski

Pingback: Polish refugees in Iran (08.08.2016) – Magda Is Learning

Ludwik Smigielski, Hi My mother and her family (not father sadly) were in polish camp Lusaka. She will be 90 years old next month. Amazing considering what you all had to endure. Her maiden name was Jodko and her mother, brother and sister all settled in England. She is the last one now and very precious.xxx

Great story – my father was at the same camp in Masindi and has photos of the old church. He too has written his memoirs from the east side of Poland, Russia, Siberia, India, Persia, Africa eventually settling in the UK.

This is an incredible piece of history that most of my father’s family lived through and eventually settled in Canada. My aunt (the oldest sibling during this ordeal) recently passed on and at her funeral I met a writer and filmmaker who is documenting this story. Over the past 6 years, he has been interviewing his grandmother (escaped to Tengeru) and my aunt (escaped to Masindi) and is close to finalizing his film “Memory is Our Homeleand”.

Stories my family protected me from until Jonathan Durand decided to create this documentary. With only a few items left for Jonathan to realize completion of this work, I am eager to help him raise the funds necessary to continue his journey and make the film available.

Anyone with ideas on the best way to raise funds, please let me know – he has already received grants from various Canadian Film boards and organizations as well as private sources. Your ideas are welcome and to view his trailor visit: http://memoryisourhomeland.com/

my partner’s family lived in tengeru all gone except the one daughter kasia cichocka who is still alive although not too well but can remember a few things

she is 91

My mother was in Tengeru. Helena Chamulka. I must watch the film …. I hope I can find it! Thank you so much.

Thank you for this, my mother Dobraslawa Ciupka and her mother Janine went on this journey and thanks to Uganda was in Masindi until 1946, Dobraslawa was my mother, she was 11 when deported with her mother to Russia. They came to England in 1946. Thank you for looking after them, unfortunately they did not have have such good care in England!