UN Charter Conference in San Francisco; June 26, 1945

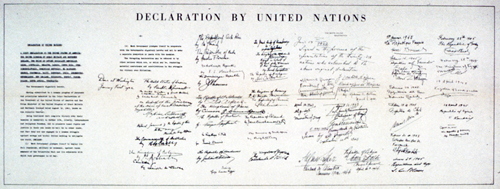

It is well known that Poland was not present at the inaugural conference of the United Nations in San Francisco in 1945, but it is not always understood that despite that Poland is nevertheless one of the founding members of the UN. Although the ceremonial inauguration of this august body had to wait until the Second World War came to an end, the United Nations was actually founded in January 1942 with the signing of the Declaration of the United Nations by the governments of the 26 founding states, including the Polish wartime government-in-exile based in London. This was the first time the term, the “United Nations,” was used in an official document. In December 1942 the Republic of Poland published a “Note addressed to the Governments of the United Nations” titled The Mass Extermination of Jews in German Occupied Poland in conjunction with arranging meetings for the now-famous Polish courier, Jan Karski.

Understanding that the Government of Poland was already a signatory to the Declaration and a founding member of the UN makes it easier to understand the dramatic protest against Poland’s exclusion made by Artur Rubinstein at a concert for the UN in San Francisco, but does nothing to explain the silence of Poland’s allies. For that, one needs to know about the diplomatic manoeuvres preceding the conference, a lesson both about the realpolitik practiced by Great Powers, and about the fragile position of small states, no matter how loyal.

The German and Soviet aggression against Poland in September 1939 compelled the Polish government and the Polish president to leave the country and seek refuge in Romania, Poland’s ally. After crossing the border, Polish officials were interned by the Romanian government and detained in special camps. In this situation, Ignacy Mościcki, the President of the Republic of Poland, decided to use his constitutional powers and designated his successor for the time of war since he could not effectively perform his duties. Consequently, a new legitimate Polish government headed by General Władysław Sikorski began to operate in France on 30 September. After the fall of France, the Polish Government-in-Exile moved to London and was recognized by many countries; it conducted its own foreign policy and operated a network of diplomatic and consular posts.

Its primary goal was to fight the occupier, cooperate with the Allies in the anti-Hitler coalition, form a Polish army, assist countless Polish refugees and try to help the suffering population in the occupied homeland. Nonetheless, in November 1939 the Polish authorities started working on a project to create a post-war system of collective security that would entail the establishment of federations in Europe.

Churchill and FDR aboard the HMS Prince of Wales for the Atlantic Charter conference.

Similar ideas were born in the minds of politicians from other countries. Even though the League of Nations (est. 1919) still existed on paper, it was obvious that it would not be able to prevent a future war since it failed to do so with this one. Against this background, the idea of a new international security system that would be able to prevent international military conflicts began to gain popularity.

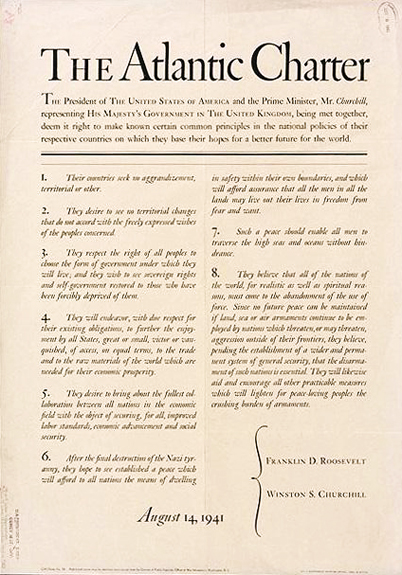

The first step towards this end was made by the US and the UK. On 9-12 August 1941, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill, meeting on board the HMS Prince of Wales, agreed on the text of an eight-point declaration, called the Atlantic Charter. The Charter, whose eighth point on the necessity to relinquish violence is probably the most important, was announced on 14 August 1941.

Within less than two months of its proclamation, on 24 September 1941, other countries from the anti-Hitler coalition, including Poland’s Government-in-Exile, acceded to the Charter. The Polish authorities were very satisfied with the general tone of the Charter, but proposed additional declarations to indicate how Poland would interpret its provisions to best protect Poland’s interests, in particular in territory-related matters.

Atlantic Charter official document; Aug. 14, 1941

Accession to the Charter and the accompanying internationalisation of issues relating to the establishment of a new security system quickly yielded results. As early as January 1942, the Declaration by the United Nations (the Washington Declaration) was signed. The Declaration was originally adhered to by twenty-six countries, including Poland, with other countries, mainly from South America, subscribing to it later on. The signatories undertook to struggle for victory over Hitlerism and ruled out the possibility of signing a separatist peace treaty with Berlin. It is also important to mention that the Declaration was the first official document that used the term the “United Nations” and for this reason it is considered the foundation of the current UN system.

In the years that followed, the matter was discussed by representatives of the US, the UK and the Soviet Union during a special conference held in Moscow (October 1943), in Tehran and in other places. Things began to take shape in October 1944 during the so-called preliminary conference at Dumbarton Oaks. The conference was attended by representatives of China, the US, the UK, and the Soviet Union who drafted the charter of the future United Nations. The details of the document were worked out by the Big Three at the Yalta conference, which paved the way for convening the founding conference.

Unfortunately, Poland’s international standing weakened during the last years of war. In July 1941, following Germany’s aggression against the Soviet Union in June, the Polish Government re-established diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union (and started to organise the Polish Armed Forces in the East) only to see these ties broken less than two years later. Stalin severed diplomatic relations because of his objections to Poland’s efforts to find out the truth about the Katyń massacre (the killing of 20,000 Polish officers). Although the mass executions were carried out by the NKVD with Stalin’s knowledge and consent, “Uncle Joe” insisted that the responsibility for the mass murders fell on the Germans. Stalin groundlessly accused the Polish Government-in-Exile of cooperating with Hitler and on this pretext severed diplomatic relations with Poland. Another reason why the country’s standing with the Allies weakened was the tragic death of Prime Minister Władysław Sikorski in a plane crash over Gibraltar. His successor had less influence over the policies of London and Washington. On top of that, the Red Army fighting Germany crossed Poland’s pre-war border in 1944 and began to extend its control over the territory. Stalin set up his puppet government, the Interim Government of the Republic of Poland, and established diplomatic relations with it.

Yalta. The Big 3.

But it was at the Yalta Conference that the most important decisions were taken. The Western Allies reaffirmed their consent to the annexation of a part of Poland’s territory by the Soviet Union and to adjoin Poland to its sphere of influence. The conference also determined that Poland would have a new government formed with representatives of the emigration and of the Interim Government of the Republic of Poland controlled by Stalin. The government was also to include representatives of political groups at home.

In the meantime, on 26 April 1945 the founding conference of the UN began in San Francisco and the issue of Poland’s participation became the proverbial bone of contention. Even though more than two months had passed since the Yalta Conference, its postulate to form a new government was yet to be carried out. The United Kingdom and the United States demanded the attendance of a representative of the Polish Government-in-Exile which they recognized; the Soviet Union protested and, in turn, requested the presence of a Polish delegate controlled by the USSR.

In consequence, Poland was not officially represented at the San Francisco Conference, even though the Polish Government-in-Exile sent its members, albeit in an unofficial capacity, as did the Interim Government of the Republic of Poland which had its representatives accredited as press correspondents. The San Francisco Conference ended on 26 June 1945 with the signing of the United Nations Charter by representatives of fifty countries. They decided to leave an empty space under the text of the UN Charter to be filed in later with a Polish signature. This idea took some time to materialise. The Provisional Government of National Unity with Stanisław Mikołajczyk as Deputy Prime Minister was formed as late as 28 June, 1945. On 5 July, 1945, the US and the UK recognised the new government as Poland’s legitimate authority and at the same time withdrew their recognition for the Polish Government-in-Exile.

Formalities had to be completed and this task fell to the government of the United States, the guardian of the UN Charter. Consequently, on 11 September 1945, the US Embassy in Warsaw, “as the depositary of the United Nations Charter,” addressed a note to the Polish government saying that the United States intended to submit “the Charter to accredited representatives of the Polish Government” for signature.

The original 26 signatories were: the US, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, China, Australia, Belgium, Canada, Costa Rica, Cuba, Czechoslovakia, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Greece, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, India, Luxembourg, Netherlands, New Zealand, Nicaragua, Norway, Panama, Poland, Union of South Africa, Yugoslavia.

The signature was affixed by Wincenty Rzymowski, the Minister for Foreign Affairs in the Provisional Government of National Unity on 15 October 1945, even though 16 October was put as the official date. His signature did not spell the end of the ratification procedure, which was completed on 24 October when Janusz Żòłtowski, chargé d’affaires at the Polish Embassy in Washington, delivered the official ratification document to the Americans and the US Secretary of State signed a special “Protocol of Deposit of Ratification.” Hence, 24 October, 1945 is officially recognized as the founding date of the United Nations, while Poland, even though it did not attend the founding conference, is recognised as an original Member of the UN. The communist authorities in Warsaw did not miss the opportunity to make a political statement out of the signature and in a declaration issued “at the time of signing the UN Charter” considered it “its obligation to state” that “due to formal, and rather incidental reasons, the Polish government was not invited to attend the San Francisco Conference.” Representatives of the Polish Government in-Exile surely thought differently about the “incidental” character of those reasons. The decision taken at the Yalta Conference and the ensuing lack of an invitation for a representative of Poland to attend the San Francisco conference was interpreted by Poles living at home and abroad as a symbol of betrayal of Poland by the West, which left its former ally at the mercy of the Soviet Union’s totalitarian rule. The withdrawal of recognition from the legitimate Government-in-Exile and decisions that led to the formation of a government in Poland that was controlled by Stalin and did not have the support of the Polish people contravened the very ideas of democracy and the goals enshrined in the United Nations Charter. The Polish Government-in-Exile would send official protests, but could not change the course of history.

In conclusion it should be added that Poland was likewise not represented at the London Victory Parade in June 1946 due to the Soviet authorities’ protest to the participation of the Polish Armed Forces in the West and its demand that a delegate of the Polish People’s Army controlled by Moscow attend the parade. In effect, even though Poland was the only country that fought Hitler’s Germany from day one until the end of the war, not even one Polish soldier was present during the London parade.

CR

Translation by the Polish MFA

Pingback: Welcome to Fall 2015!

Fascinating! Dziękuje bardzo, Minister Długołęcki.

Montage, 70th anniversary of the United Nations:

http://www.polishclubsf.org/Rubinstein%20UN%201945%202015.pdf

Thank you for this concise history of these dramatic events; recalled oh so sadly, it all still makes my blood boil. The only thing that calms me down is the daily realization that we as Poles all have, that the freedom of 1989 finally happened, and free, democratic Poland goes from strength to strength!

Pingback: The Politics of Morality: The Church, the State, and Reproductive Rights in Postsocialist Poland