The Dark Heart of Hitler’s Europe: Nazi Rule in Poland Under the General Government

The Dark Heart of Hitler’s Europe: Nazi Rule in Poland Under the General Government

By Martin Winstone

I.B. Tauris, London 2014

The historiography of Poland owes a great deal to its relative “outsiders,” who cast familiar historical subjects in a new light. Martin Winstone’s book, The Dark Heart of Hitler’s Europe: Nazi Rule in Poland Under the General Government (2014) belongs in this category. Winstone is an Educational Officer for the Holocaust Educational Trust (HET), a London-based charity founded in 1988, whose aim is to “educate young people of every background about the Holocaust and the important lessons to be learned for today.” His previous work focused on the geography of the Holocaust.

As the title suggests, the subject of the book is the General Government (GG), a zone of German occupation carved out of the Second Polish Republic. At its maximum, it would come to hold a population of approximately 17 million – almost 50% of Poland’s prewar population – that would witness and undergo human tragedy of biblical proportions. Considering that “one in every three victims of the Holocaust was murdered in the GG, more than anywhere else in Europe,” that it became the locus of the death camps of Operation Reinhard (codename for the plan to murder Polish Jews) and the Warsaw Ghetto (the largest in all of occupied Europe), the General Government arguably represents the ground zero of the Holocaust.

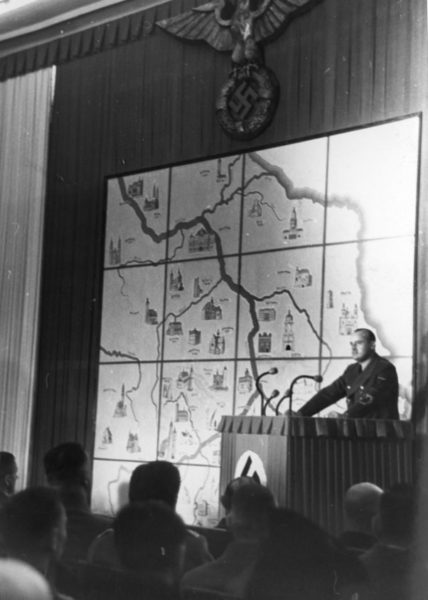

Hans Frank addresses Nazi leaders in an undated photo. Map of “colonial General Government” in the background. The name “Poland” was banned.

Yet astonishingly, it is also a subject for which no monograph has ever been produced. Throughout the decades, historical research on the GG has proceeded in a piecemeal fashion, with important studies on particular themes, districts, or regions. The Dark Heart of Hitler’s Europe, however, is not a historical monograph in the strict sense, though it is a significant step in that direction. It is the first English-language study to examine the General Government as a single entity aimed at giving “some sense of the strange reality of life and death” of this territory to a wider audience. The work – divided into nine chapters, plus an epilogue – is not based on archival findings, but is a brisk synthesis of the most recent scholarship and published document collections, mostly in English and German.

Among Winstone’s many insights, two analytical features combine to make the book a remarkable read. The first is situating this territory within a framework of Nazi German colonialism, a theme the author develops most prominently in the Introduction (“’The Wild East’), Chapter 1 (“’The Devil’s Work’: Origins”) and Chapter 2 (“’Gangster Gau’: The Regime”), before settling into a more familiar narrative in subsequent chapters. Here, his understanding reflects the wider colonial “turn” in the scholarship on genocide and the Holocaust in the last 15 years.

In terms of the GG, the only sustained colonial lens on the region to date is a seminal essay by historians David Furber and Wendy Lower, which Winstone draws on. These authors make a powerful argument that Nazi leaders were inherently “empire builders” in the eastern territories. In Nazi thinking, the Lebensraum of the European “East” found inspiration in the “Manifest Destiny” of the United States. Hitler and Hans Frank both saw a kind of Indian or Native American in the Poles, but Hitler leaned toward North America and Frank toward India as models of rule.

Further, argue Furber and Lower, the GG was a zone where two ideal types of colonialism were in conflict: that of the “settlement-oriented SS” (Heinrich Himmler) and the “exploitation-oriented civil administration” (Hans Frank). As this conflict unfolded in the course of the war, “it led both groups to unite over the extermination of Jews while clashing over exterminating non-Jewish, non-German inhabitants.” These arguments find support in the work of Jürgen Zimmerer, German historian of the genocide of the Herero and Nama people in German Southwest Africa (modern-day Namibia) and author of From Windhoek to Auschwitz: On the Relationship Between Colonialism and the Holocaust (2015). In terms of the GG, Zimmerer likewise sees a thread of “genocidal colonialism” running “from Windhuk to Warsaw.”

The GG as the heart of the German Wild East. Gov. Hans Frank (4th from left) with German officers on the German-Soviet border. The sign reads “The General Government for the Occupied Polish Territories”—the last four words were struck from the GG’s title after concerns arose about its implications in international law.

Such a historical line of descent helps to place the GG on the broader map of European colonialism. Still, one may wonder why such recognition has taken so long to take root among scholars. It was the First World War that swept away the continent’s ancient empires, giving rise to national liberation movements behind which lurked renewed imperial projects. Yet of the two major interwar fascist movements, Italian and German, Nazism was not interested in overseas colonies. Among the European powers, the 19th c. Imperial Germany was a latecomer to the “Scramble for Africa,” only to be stripped of its African colonies after Versailles. The Nazi imperial project of the “Third Empire” thus looked to internal colonization of the European continent, articulated in Hitler’s vision of Lebensraum in the European “East.” subject of sorts.

It is also tempting to see the GG as a direct colonial descendent of the so-called Imperial Government-General of Warsaw, an administrative civil district created by Imperial Germany during the First World War in August 1915. However, three young historians, Winson Chu, Jesse Kauffman, and Michael Meng, have argued against over-emphasizing colonial continuities across Imperial, Weimar and Nazi periods in relation to Eastern Europe or what would amount to a new Sonderweg thesis, or Germany’s “special path” in relation to Eastern Europe. Rather, they see Nazi policies as reflecting a significant rupture from earlier German practices in the region during the Imperial and Weimar.

Although in Winstone’s framing, the narrative does not harken back to the German imperialism of the 19th century, the colonial character of the GG becomes unmistakeable. Winstone is at his story-telling best in beginning the book with the remarkable – if not obscene – oddity that was Baedekers Generalgouvernement – a travel guide for German tourists published in the spring of 1943 (research for the book was carried out in the summer and fall of 1942 – the peak of ghetto liquidations and violence). From the very outset of the war, we are told of German beliefs that “Asia starts in Poland” and descriptions of Ostjuden (East European Jews) as “terrible Asiatic hordes,” Slavic people as lacking “state-forming powers,” and Poles as intrinsically “incapable of state-building.” The Governor of the GG, Hans Frank – at once “King of Poland,” enlightened despot; self-styled Renaissance prince; and NSDP “Old Fighter” – was quick to declare the GG as “the first colonial territory of the German nation.”

Nazi Empire-building. Celebrations of the first anniversary of the outbreak of war on September 1, 1940. Gov. Frank and guests in the Palace of Fine Arts in Kraków during an exhibit entitled “German Activity in the Vistula Space.”

The author reminds readers that the invasion of Poland was the “Third Reich’s first war.” The territory of the GG would serve as a link in the broader Nazification of the German army and the radicalization of violence throughout Europe. Lessons learned in the murder of civilians and Polish POWs in 1939 would be applied and expanded in other regions. Here, between the qualitative leap from the limited race war of 1939 to the apocalyptic Operation Barbarossa of 1941, Winstone might have mentioned the “missing link” of the murder of at least 3,000 black POWs from France’s West Africa colonies between May and June 1940 during the French Campaign. Knowledge of these massacres has been peripheral to French memory and practically nonexistent in Germany, brought to light by historian Raffael Scheck in his book, Hitler’s African Victims: The German Army Massacres of Black French Soldiers in 1940 (2006). Drawing a connection between these events and AB-Aktion in Poland around the same time, in which some 3,500 members of the intelligentsia were killed, widens the colonial lens. Winstone might have also added that the military practice of so-called “pacifications” or Befriedungsaktionen, that punctured everyday life under occupation in Poland, itself had colonial origins.

This retelling of the GG as the “heart of the German ‘Wild East’” and the “Dark Heart” of Nazi German colonialism, as found in the title, carries overtones of European colonialism in the Belgian Congo of Joseph Conrad’s novella – this time unfolding under the Western eyes of Józef Korzeniowski’s own native realm. It could be said that the German Herrenmenschen and district chiefs did not look abroad for their Herero and Nama subjects, but could find them in the Poles and Jews of the GG.

Yet the GG holds an unusual place in the history of colonialism: to establish a more traditional colonial relationship meant dismantling a modern European state. Long-term economic plans thus envisioned stripping Poland’s industrial infrastructure to make it dependent on German industrial products in what would be reduced to a largely agricultural country (with predominantly German cities). Steps were taken in this direction. Walter Emmerich, the head of the GG’s economics department, used the GG as a dumping ground for unsold German products. Further, the maxim of divide et impera found expression under various guises. Initially, Frank believed he could win over workers and peasants by shared hostility to Polish capitalists. The ethnic divisions and tensions of the Second Polish Republic could be utilized to shatter notions of Polish political citizenship into smaller “races.” Other planners argued for the “destruction of Jewish enterprises as a precondition for the emergence of a Polish middle class.”

In the long-term, the “overriding objective remains the reinfusion of the Vistula space with German people and with German consciousness in every sense,” wrote an employee of a Nazi think tank, the Institut für deutsche Ostarbeit (Institute for German Work in the East). In the short-term, the GG was always to benefit the German war economy. Thus, in the period from 1939-1941, different variations of colonial rule animated Nazi rulers, which ranged from initial plans for Poland as a “reservation” for the Jews – with variations in Eichmann’s Nisko Plan and the Lublin Reservation, followed by the Madagascar Plan – to a dumping ground for the population expelled from the Reich, and a “Polish reservation, a great Polish work camp.” This was a colonialism stripped of any “civilizing mission” (something Hitler objected to) and increasingly reduced to a logic of sheer exploitation.

The second major strength of the book is that it shows how these visions competed and co-existed with each other within a single territorial unit – and how the course of the war both constrained and encouraged their constituent parts. Constant war meant that these plans were often postponed or limited, but it was the invasion of the Soviet Union that cleared the way for truly “intoxicating vistas,” and sealed the decision to implement the ambitious Generalplan Ost. The Generalplan broadly outlined the deportation of more than 30 million racial undesirables, leaving behind 14 million Slavs as a pool of forced laborers, and settling the territory with Germanic peoples (including the Dutch and Norwegians).

For the GG, it meant replacing the 12 million Polish inhabitants with 4-5 million Germans, so that it would become “as German as the Rhineland.” Frank petitioned to receive Poland’s Eastern Borderlands (Kresy), but was only given District Galicia (Galizien), which more than doubled the size of the GG. The district magnified some of the worst features of the GG in what Winstone calls a “nakedly colonial regime” – so bad that it earned the nickname “Skandalizien,” adding to the existing moniker for the GG among Germans as “Gangster Gau” (Gau meaning “district” in German). It is perhaps no accident then that the Holocaust in the GG began in Galicia in late 1941. In neighboring Reichkommissarriat Ukraine, its ruler Erich Koch was fond of referring to Ukrainians as “niggers” and “white Negroes.”

Viewed within a single territory, Winstone’s narrative is able to demonstrate links between policies aimed at different groups in the GG and the entangled victimization that arose from it. Thus, the turning of the tide that came with the “euphoria of victory” (as historian Christopher Browning called it) in the fall of 1941 toward the mass killing of Jews is linked with the development of Generalplan Ost. Likewise, Himmler’s “designation of the General Government as a German settlement zone” fuelled ghetto creation and the deportations of Jews in the spring and summer of 1942. Also at this time, Odilo Globocnik’s settlement of the Lublin district by German communities from the Baltic states and Transylvania aimed to “encircle” and “gradually crush economically and biologically” the remaining Poles.

Nazi practices also marked a break with traditional forms of European colonialism, the Holocaust a central case in point. Winstone points to the crucial role of regional and local factors in its evolution. Although the desire to remove the Jews from the GG met a consensus across all German civil and police administrations, its implementation through mass shootings, destruction through labor, and death camps were all regional initiatives. Winstone shows how each district had the potential to function as a separate fiefdom when it came to approaching its “Jewish question.” For example, in district Galicia, it was district Governor Karl Lasch and police chief Fritz Katzmann, who pushed for radical measures. Katzmann’s solution was to put Jews to work on a major road that stretched from Lwów to southern Russia, in a conscious policy of extermination through labor. Likewise, it is possible that the death camps of Bełżec and Sobibór, whose scope was initially confined to district Lublin, originated as regional measures before the demand for deportation spread to the whole of GG and beyond.

And again, a perverse colonial logic is discernible in the reports that detailed the wealth that the Holocaust had generated, where the bodies of European Jews were turned into a natural resource to be mined for their precious metals and catalogued as a kind of colonial booty. In his June 1943 report on Galicia, Katzmann went as far as to itemize the inventory down to “necklaces, earrings and brooches, 11,730 kg in gold teeth and dentures.” Shocking as it may be, it is hardly surprising that the death camps deeply transformed local economies, where impoverished villages suddenly “looked European,” in the words of a local observer, Józef Gorski, with sites of killing notoriously attracting “gold diggers” after the war.

There is little to criticize in this excellent and necessary study. Winstone writes with remarkable balance, humanity, and sensitivity toward his subjects without ever catering to any martyrological narrative. Specialists of the Second World War in Poland and the Holocaust may learn little that is new, but they are likely to be impressed by Winstone’s power of synthesis. It is a retelling that puts cutting-edge scholarship on genocide and ethnic cleansing at the heart of the story. The book is eminently readable. Not weighed down by too many footnotes and academic details, it can also be appreciated by a non-specialist.

The author expresses words of praise for “democratic Poland” in leading the way in Europe “in confronting the darkest corners of the darkest hours of its history.” Given the recent change in political winds and the desire to turn back the clock on this very confrontation, combined with proposed legislation to criminalize language that would suggest Polish complicity in the crimes of the Third Reich, he may have spoken too soon. Yet as he reminds the reader, the “less than wholly edifying picture” of Gentile behavior during the Holocaust is “not a judgment on Poles (or Ukrainians) but, sadly, on human nature” in a “pattern repeated across the continent.” As the Holocaust in occupied Poland still remains a largely misunderstood event, The Dark Heart of Hitler’s Europe should all the more be required reading.

For scholars of the Holocaust, The Dark Heart of Hitler’s Europe should be read alongside Wendy Lower’s study of neighboring Reichkommissariat Ukraine in Nazi Empire-Building and the Holocaust in Ukraine, which excavates the colonial nature of German rule in Ukraine. Beyond Poland, it is hoped that the story of the GG will be integrated into the broader history of European colonialism.

For all its breathtaking horror, the GG represents but a glimpse of the Lebensraum envisioned in the Thousand-Year Reich at the heart of the European continent. For Poles and Jews, though “unequal victims,” the book might serve as a reminder that both were colonial subjects of the same regime slated for eventual destruction. For most others, it would likely be an introduction to the overall barbarity of the German occupation.

CR

All images from Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe 2-4714, by permission, courtesy Tom Frydel.

Poles and Jews were “unequal” victims? Evidently the reviewer has never heard of “Generalplan Ost” . It set the agenda of eliminating the Polish national group no later than 1975. Polish children of suitable racial stock, under about the age of 7, were to be exported to Germany, and there placed with German parents. They were thus to be Germanized . Able bodied men and women were to be used as slaves. They were to be sterilized, and not allowed to marry. They were not to be educated, except to the extent of being able to sign their names. The rest were to be “resettled in the east”. You can guess what that means.