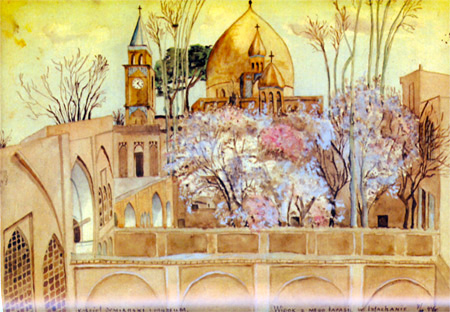

Artwork by Isfahan student Helena Waszczuk, 1944

Inscription at bottom reads:

Armenian Cathedral & Museum

The view from my terrace in Isfahan

7/44

In the spring of 1942 in anticipation of the arrival of Polish refugees from captivity in the USSR, a city of 2,000 tents was hastily erected on the shores of the Caspian Sea at Pahlavi. Just how many there would be nobody knew, but only days earlier word had arrived that there could be as many as 10,000 thousand woman and children along with the soldiers in the army of General Anders. Would these facilities be enough?

Among those watching the flotilla of coal ships slowly approaching were Polish, British and Iranian officials; it was the Iranian army that had equipped and erected this refugee reception centre under the direction of General Esfendiari. The complex included bathhouses and disinfection facilities, latrines, hospitals and dormitories, bakeries and laundries. Writing in Pars Times, Edinburgh-based writer Ryszard Antolak noted that supplies had been requisitioned from among the local population, including chairs from local cinemas.

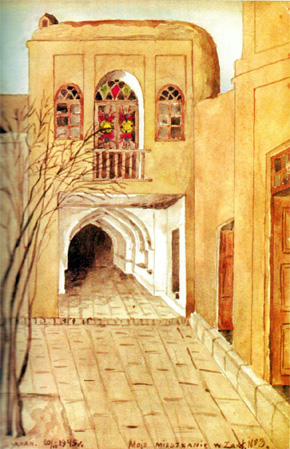

Artwork by Isfahan student Helena Waszczuk, 1945

Inscription at bottom reads:

“My residence”

As the ships, packed beyond any conceivable safety standards, dropped anchor, the cargo of sick, filthy, smelly humans moved onto small boats for the last crossing in shallow waters. Once ashore they collapsed on the beach, some praying, others delirious with joy, some simply because they could not continue, among them some who died the moment they reached freedom.

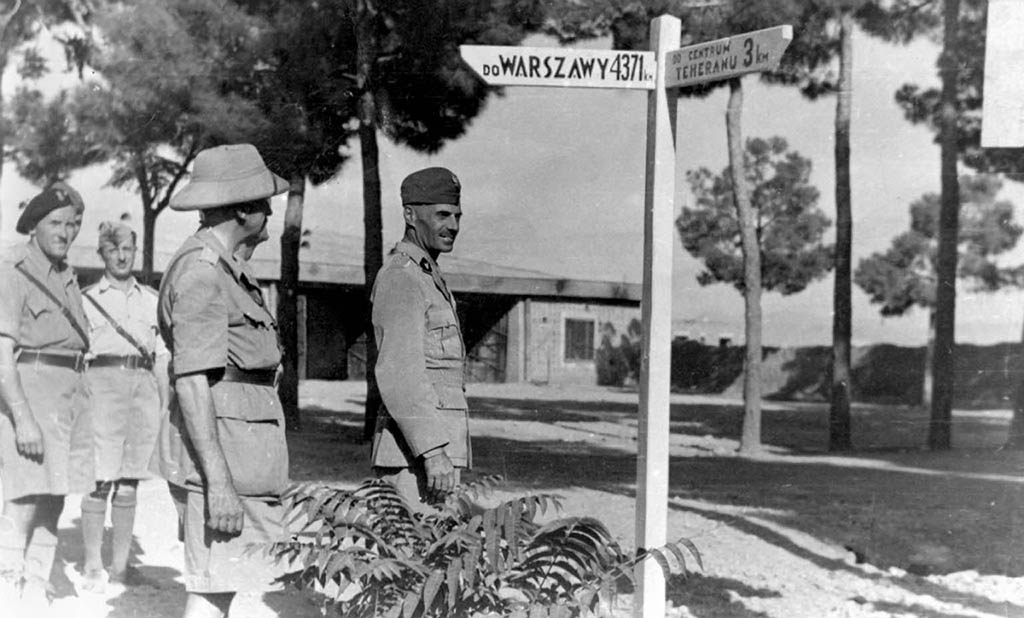

During the war, Iran – often referred to as Persia by Poles at that time – was a hotbed of intrigue, nominally independent but unofficially occupied by the British and the Soviets, and harboring a host of international spies, notably German, plus assorted refugees.

The tent city in Pahlavi was overwhelmed: the flotilla had brought many more civilians than expected, including 18,000 children of all ages, many of them terribly ill, all of them filthy and lice-infested. The ones with typhus and other infectious diseases were quarantined, but others, after showering and delousing were moved to hospitals in Tehran. For the healthier ones, the Poles established schools within days realizing that addressing intellectual, cultural and social development was vital to their long-term recovery.

While thousands of refugees were sent to Tehran for treatment in hospitals or to transit camps to await further relocation, as early as April 1942 it was decided to send many very young orphans to Isfahan, some 340 kilometers south of Tehran. Situated at an altitude of 1590 meters, its benign climate, lush gardens, magnificent architecture and cosmopolitan culture would provide nourishment for both body and soul.

Krystyna Skwarko, a remarkable Polish teacher and humanitarian, herself a deportee, dedicated her life to orphaned children starting in Russia and then on to Isfahan and New Zealand. She left behind a superb historical record titled “The Invited.” The most gifted writer of fiction could not possibly invent a story to match this extraordinary odyssey.

Carpet woven by Polish students at Isfahan

The first contingent of very young children sent to Isfahan was placed in the care of the Sisters of Charity, the Salesian Fathers, and a Protestant missionary couple, a Mr. and Mrs. Illiff. A few Polish guardians accompanied them. But it was not long before Isfahan became home to over 2,000 children, housed in various accommodations, both convents and private homes specially rented for them, a total of 17 residences. Six homes were in the Armenian sector, one of them rented from Armenian clergy. Medical care was provided at both the British and the Armenian hospitals. In time the Polish Delegation in Tehran sent two Polish doctors and a dentist. Each residence had its school, the Polish government sent more teachers, and shortly after, textbooks arrived, published by the Polish army by then in Palestine. A priest arrived to provide more formal religious education and many children made their First Communion. Some of the older girls attended carpet-weaving classes, working with a well-known local artist for the designs. Sports, craft, games, concerts and theatrical performances rounded out their days.

Isfahan: Minarets of Shah Mosque

By Ralf Schumacher Dresden via Wikimedia Commons

The Persian people, Skwarko noted, were friendly and generous, and welcomed them with gifts of dates, nuts, roasted peas with raisins, and juicy pomegranates. As the children recovered their health, strength and spirits, they started visiting mosques, museums and bazaars, always greeted with friendship and kindness. On the occasion of the young Shah’s visit to the children, one student delivered a welcoming address in Farsi. Years later, when the Shah and the Empress visited New Zealand in the 1970s, he made a special request for a meeting with the Polish children who had once lived in Isfahan.

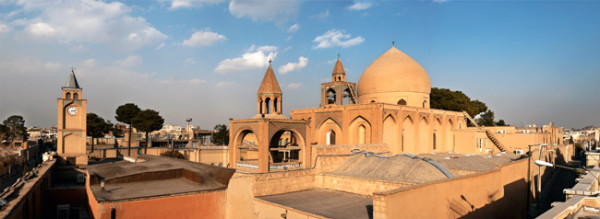

Isfahan: Panoramic view of Vank Cathedral

By Ggia via Wikimedia Commons

CR highly recommends a collective memoir* written by some of the students from the Polish schools in Isfahan, not only for a record of their own journey, but very much for their impressions of the land and the people who hosted them. When their health was restored, their school curriculum included field trips to places of interest – and there were so many – including many museums. A young diarist writing about a visit to the Armenian museum, situated next to the magnificent Armenian cathedral, made the observation that the collection included ancient works of art, manuscripts, carpets, and costumes but no weapons, which led him to conclude that “Armenians are not a belligerent people.” A confirmation of the very favorable opinion the young Poles had already formed of the Armenian people.

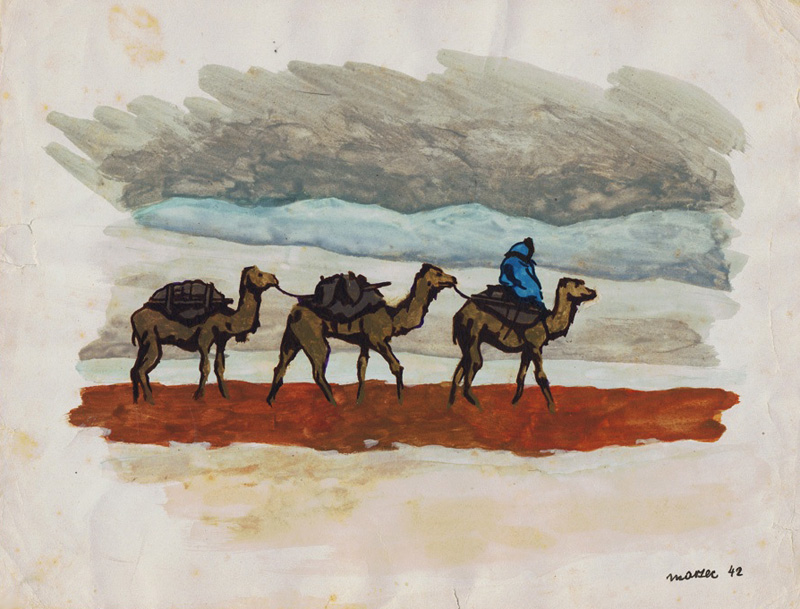

Their Scouting groups went on many hikes and excursions where they could see deserts and mountains, small towns, bazaars and camel caravans. Always accompanied by their educators, they learned much about the history, culture and peoples of the region.

Isfahan: The Si-o-se Pol Bridge over the Zayandeh River

By Shahab.mg via Wikimedia Commons

Among the most exciting excursions for the older students was the trip to Kuh-Sofe Mountain (Kuh-e-Soffeh), which they climbed. From the top they could see all of the Isfahan valley and the Zaindeh River (Zayandeh), the river of life that nourished all of Isfahan. They also visited Shiraz, “a town of gardens full of roses, lemon trees and cypresses, a town of wine and poetry,” once home to two of the greatest Persian poets, Saadi and Hafiz.

Perhaps the most spectacular site, however, was Persepolis, the amazing city of ruins that still testified to the magnificence of ancient Persia. As they gazed at the entrance to what was once the Throne Room, the ruins of palaces and the sculptures of “The Immortals,” the students imagined the courts of Xerxes and Darius. Who could have ever imagined they would attend such a school after the barbaric treatment they had endured in the Soviet Union?

Although new cohorts of children were arriving in Isfahan, everyone knew that Iran could not be a permanent home. Plans were readied for those children who had recovered their strength to move on to more permanent homes. Sorrowfully, several hundred embarked on the long journey to South Africa. Almost a thousand went on an even longer journey to New Zealand, which quite possibly turned out to be the happiest chapter in the great wartime saga of the Polish children deported to the Soviet Gulag. Although ultimately they could not return to their homes in Poland but would go on to exile in other lands, the care they received under the careful eye of the Government-in-Exile prepared them for the challenges they would have to face.

As writer Ryszard Antolak noted in Pars Times, “The deepest imprint of the Polish sojourn in Iran can be found in the memoirs and narratives of those who lived through it. The debt and gratitude felt by the exiles towards their host country echoes warmly throughout all literature. The kindness and sympathy of the ordinary Iranian population towards the Poles is everywhere spoken of.” Antolak also noted that Dariusz is a very popular boy’s name in Poland, perhaps influenced from the contacts between Poland and Persia going back to Sobieski’s reign. Certainly the Polish children’s experience in Isfahan would reinforce this. The city is frequently referred to as the “City of Polish Children.”

CR

* CR highly recommends the collective work by the Association of Former Pupils of the Polish Schools, Isfahan & Lebanon: Isfahan: City of Polish Children, winner of the Prize of the Union of Polish Writers Abroad for Best Polish Book Published Outside Poland in 1987.

Pingback: The Indomitable Spirit of Halina Babinska: A Very Special Coming of Age Story

Pingback: February 1940: Exile, Odyssey, Redemption

Pingback: Welcome to our Spring 2015 issue!

Dear Irene, after reading your moving and very thoughtful article in the Ottawa Citizen, I wanted to find out more about you. I just read your story of the Polish children in Isfahan: events I did not know about at all.

Born in Holland in 1926, I lived through the German occupation as teenager. To tell the whole story of how I ended up in Ottawa would be much too long. But I would be happy to meet once, in Ottawa or in Hudson, Quebec.

In any case, I thank you for your article.

Best regards, Theo

Theo Geraets, professor emeritus, University of Ottawa

Tel. 614-730-7870

Pingback: Bulletin Board Fall 2015

I am Stanley March (stanislaw marczynski) 81,now live-in USA since 1950. I am one of those

Polish orphans that resided in Isfahan, Meshed,Ahwaz and camp 3 in Teheran. Later on, I was sent to Valivade in Kolhapur, India. In 1948 we were sent to camp Koja near Kampala in Uganda East Africa. I have fond memories in my stays in Iran, India and Africa in contrast with Siberia where I remember extreme cold and hunger.

Is Helena Waszczuk alive ? I would like to contact her. Any assistance welcomed and appreciated.

Dear Stanley,

Hope you are well. I am very glad that I ran into this page and read your comment in here. I am writing a chapter for a WWII book and I am going to be focusing on the Poles stay in Iran. I was wondering if you could please give me your contact.

Best,

Mehdi

This was so wonderful thank you so much for sharing . I have to say Stanley March I have to admit that made me have tears of joy , What an exciting life you have led and still lead . I bet you could write your own book , wow very Awsome

Hi I was wondering if anyone could tell me where I could find a copy new or old of the book Isfahan city of polish children as I would like to give a copy of it to my cousin Karolina MICHULKA / Migulka who was one of those children. Who came from Siberia to Persia 1942 If anyone knows where I can get a copy please contact me on this email address. Ivad@orangehome.co.uk

My father was one of the children who went to South Africa then came to Britain with his brother his name is Jan Wojcik his brother was called tony

My mother and aunt were here. Their uncle and aunt found them through the Red Cross. Irena and Daniella Hebda.

Dear commentators above,

it is so interesting to read about Your family stories. Do You or the members of Your family who were there still speak some words of Farsi? How do You or they remember the days in Iran? How do You handle these memories?

I’m asking that much because I’m currently writing my master thesis about the Poles in Iran in WWII and what remains of these years in today’s culture of remembrance. If You are interested to help me (and to get into an academic paper), I’d be very happy if You’d contact me: lena.schraml@student.uni-halle.de

Thanks 🙂

Lovely

مهربانان

My husband Ryszard Sierakowski and his sister Irena were two of the children of Isfahan. They were reunited with their mother and went to Lebanon, and from there to Egypt and arrived in the UK in 1947.

I have a english version of this book looking to get more copies if anyone knows how and where! Thank you for your help!

Hello, My name is Christopher (Chris) Bik. My mother wrote a diary of her experience as a young girl in Siberia where she was taken to from Poland along with her two sisters and mother. I also have photos of her time in Iran which she also wrote about. Her diary is being published in Poland and I would like to have it in English. As I looked on the internet “The Children of Esfahan” I was stunned to see photographs of my mother, aunt and grandmother. No one new their names at that time. I would love to communicate with you. Thanks.

Dear Irene.

I would like to inform you I am working on my dissertation with the title of Polish children in Isfahan through second world war. if it is possible please email me.

regards

zahra shiran

my email: zahra_shiran@yahoo.com

Dear all,

I am an Armenian from Iran (Tehran, not Isfahan) and I am really touched by the story of the Poles finding refuge in Iran, I have visited the Polish cemetery in Tehran several times, very very impressive and saddening at the same time. My own grandparents are buried in the same cemetery complex in Tehran (Doulab). I found many of the above Polish names of people leaving comments above in my book, with an extensive list of almost all Polish refugees in Iran…such a pity no one left an e-mail address….. anyway: for anyone interested, the cemetery can be visited online too: http://doulabcemetery.com/en/default.asp

How can I get information on names of Polish children of Isfahan? My fathers younger sister was taken in Persia by some woman who spoke polish. Never to be found. Cannot get if she may have died as a small child or was relocated to a diffrent country. She might of been 4 or 5 years old. My father was 6 or 7 years old. Her Name was Danusia Wilkosz .

This caught my attention as my late aunt Irena who has only recently passed, had travelled through this region from Wołyn. Her maiden name was Tomaszewska. I wonder if she was actually there. I have photos, but don’t really know where exactly she was in Persia.

It was good to learn more of what happened.

My father Bolesław was one of those militar official of Anders Army who was relesead from Kolyma /Siberia, after that enjoined Anders Army in Middle Est.He always spoke very well about people of this area.Persian were so kindly with polish man. A “mulah”( religious) gave to my father an old big book handwriting in papiro from 12th. century.The mulah asked Dad to save this important book/ document from red russian destroy. I still having it, but didn’t decide yet what to do…or at whom can I donate ?

What is better to do ??

Dear Irene. So wonderfully written, and leaves nothing out that could be mistaken, or for any inaccuracies of how this human mass of suffering came to be there.

Gabriela, the book you have is so important to the memory of your father, and more importantly, to the Polish Nation. The children who resided at Isfahan have an everlasting memory through this book. I would like to think it’s memory, and that of the Polish children, and the wonderful Iranian people, and their hospitality, could be remembered through the Sikorsky institute and museum, in London. Age is not on our side and I suggest you give it some consideration.

I loved this story and would like the book if available

For Chris Bik,

I hope you see this. I am in the process of translating your mother’s book at IPN and very happy about it. Would love to hear from you. sheri.torgrimson@ipn.gov.pl

Sheri Pawlikowska

Hello

Does anyone know if there’s a way to access a copy of the book mentioned? It seems to be out of print everywhere I search. Thank you