General Edward Rowny is almost 96 years on the Sunday afternoon I visit him at his Maryland home in late March 2012.

General Edward Rowny is almost 96 years on the Sunday afternoon I visit him at his Maryland home in late March 2012.

He’s made an indelible mark on U.S. 20th century history: He’s commanded troops in World War II, Korea, Vietnam. He’s advised five U.S. presidents – from Nixon through Bush – and their special advisers on arms control. For his work as President Ronald Reagan’s chief arms negotiator with the Soviet Union, he was awarded the Presidential Citizen’s Medal. The inscription on his medal reads, “one of the principal architects of peace through strength policy.”

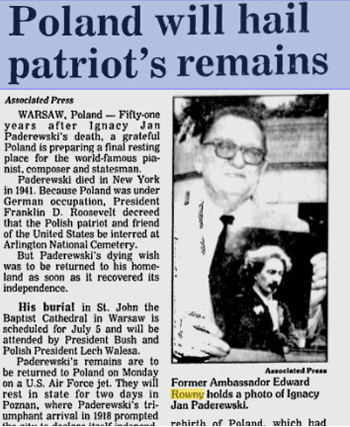

He’s also played an important role in Poland’s history: As a young man, he attended Ignacy Jan Paderewski’s funeral in New York City. 50 years later, he escorted Paderewski’s remains from the U.S. national cemetery – Arlington – to an independent Poland.

And his work continues with a scholarship foundation he’s created for Polish students to study at DC’s Georgetown University.

We chat in his study, filled with books, papers, files, and computer equipment. “Do you have a week?” he says with a laugh when we begin.

Summer Olympics: 1936, Berlin

In 1936, 19-year-old Edward Rowny was awarded a Kościuszko Foundation scholarship for a summer semester of study in Poland. Born to a Polish father and Polish-American mother, he was eager to explore his roots – and Europe.

I went to Kraków, to Jagiellonian University. There were just lectures – no exams. Kościuszko Foundation gave you a free rail pass to go all over Europe. If you left the university on a trip, they’d give you $1 a day for food. If you ate cheese and bread and a little fruit it was enough.

I made the grand tour – Venice, Rome, Florence, Vienna, London, Paris. Finally I went to Berlin for the Olympics.

It cost me $2 to get in – that was 2 days of food.

I saw an ad for an American-style breakfast at this famous hotel (during the Cold War it was in East Germany). It was pretty good, only about 50 cents. A man asked if I wanted a glass of orange juice. I said yes. When the bill came, it was $2.50, so $2 for a glass of orange juice.

I went to the Olympics. I saw Jesse Owens, the black athlete, win gold medals. I saw Hitler turn his back on him. I saw the goose-stepping Nazis. I said, my God, there’s going to be a war. We’ve got to stop these soldiers. I came home and applied for West Point.

Paderewski’s Funeral: 1941, New York

Paderewski’s Funeral: 1941, New York

I.J. Paderewski died in New York City on June 29, 1941. His funeral mass was held at St. Patrick’s Cathedral on July 3. His body could not be returned to Poland – at that time in the throes of German Nazi occupation. Instead, he was interred at the National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia, presumably till the war’s end. In reality, it would take 50 years and the fall of communism before Paderewski’s remains would be returned to a free Poland.

In the summer of 1941, Edward Rowny had just graduated from college and was on his way to West Point Military Academy.

My grandmother had been a governess before she disgraced herself by marrying a sergeant. Her family thought she should marry at least an officer. They disowned her. She and her husband came to the U.S.

A very cultured woman, she spoke five languages. She would read to us in French, Goethe in German, Mickiewicz in Polish, and translate to English for us.

She played Paderewski’s records over and over again until they were thin. She taught me about Paderewski. She said when he died, “I want you to promise me to do everything you can to get his body back to Poland.”

I went to the funeral. 5,000 people lined on the streets of New York. Cardinal Spellman gave a wonderful eulogy about how Paderewski would someday return to Poland.

President Roosevelt said, bury [Paderewski] at Arlington Cemetery – our national shrine. Our laws said, no, only U.S. citizens can be buried there. So he said, put him there temporarily until Poland will be free again.

Paderewski and JFK: 1961, Arlington Cemetery, Virginia

Paderewski and JFK: 1961, Arlington Cemetery, Virginia

In the early 1960s, President John F. Kennedy and his wife learned that Paderewski’s body was “temporarily” interred at Arlington Cemetery – but with no marker.

Brigadier General Edward Rowny was in Vietnam, commanding troops and testing helicopters as combat vehicles.

President Kennedy sent for me. His wife was a great admirer of Paderewski, and she said she was unhappy because nobody knew that Paderewski was interred at Arlington. She had [JFK] put up a marker saying, here is Paderewski’s body.

Kennedy invited me to come back from Vietnam and be part of the ceremony. I have a tape of the speech [Kennedy] made.

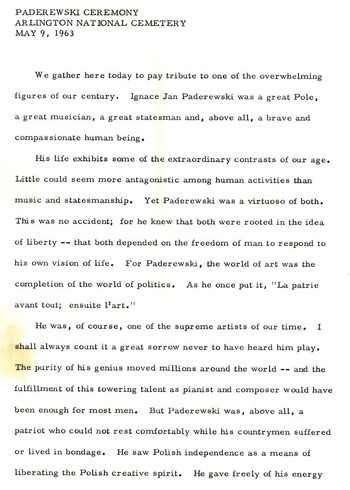

“Little could seem more antagonistic among human activities than music and statesmanship. Yet Paderewski was a virtuoso of both. This was no accident; for he knew that both were rooted in the idea of liberty — that both depended on the freedom of man to respond to his own vision of life.”

– excerpt from May 9, 1963 JFK speech at Arlington National Cemetery (left)

JFK found out [about me] from Paul Hume. [Ed. note.: Hume was the music editor for the Washington Post, 1946-1982, and the author of The Lion of Poland: The Story of Paderewski.]

I told Hume how wonderful his book was and how much I admired Paderewski. Jackie read Hume’s column in the Washington Post, that nobody knew where Paderewski’s body was. Jackie brought that to JFK’s attention. He talked to Hume and Hume told him of me.

I came from Vietnam as the “senior ranking member of the Army of Polish origin,” – I wasn’t. I don’t know who was, but I was just a brand new Brigadier General. I’m sure there were others more senior than me of Polish origin. Someday I’ll have to look that up.

Taking Paderewski Home: 1991, Arlington and Warsaw

Taking Paderewski Home: 1991, Arlington and Warsaw

Poland and the U.S. began discussions on the return of Paderewski’s body in the mid-1980s. As an arms-control negotiator during the Ronald Reagan administration, General Rowny spoke with Lech Wałęsa about Paderewski’s return in 1985 and with Polish officials in 1986 and 1989. Poland’s first non-communist Prime Minister Tadeusz Mazowiecki formally requested the body’s return in 1990. Poland’s first independently elected President, Lech Wałęsa, requested that the return happen in 1991 – after Poland’s first democratic parliamentary elections.

It was Retired Lieutenant General Rowny who planned and executed the remains’ return.

I took the body back to Poland after having been sued by a group of 18 DC lawmakers for grave robbing. They said that Paderewski loved America and he should remain in America.

I went to court.

Before I did that I went to the Library of Congress and looked for Paderewski’s will. He had no will. But he had a letter which he dictated to his sister Antonina.

The day before he died, he asked his sister to come have a glass of champagne with him. He said, we’ve lived a good, fruitful life and we should be grateful. He said, when I die, I want my heart to stay with my love. That’s all he said. He said that when he was in the U.S.

I went to the judge. I said, he wanted his heart to stay in the U.S. Ergo, his body should go somewhere else. The judge said, you’re right. With $18,000 of legal fees and $10,000 of court fees, I won the case.

When we took the body back, we had a huge parade. 10,000 airmen, soldiers, sailors, lined the streets all the way from Arlington Cemetery to the airport.

Wałęsa gave me the flag that was around Paderewski’s bier. I gave that flag to the Polish Museum in Chicago. He also gave me 2 volumes of books with [signatures of] dignitaries who came to see Paderewski when he lay in state in Warsaw, and I gave those to the Polish American Cultural Society [Ed. note: now the Kościuszko Foundation’s DC chapter].

Paderewski’s Heart: A Mystery

Paderewski’s heart was removed from his body when he died, and eventually placed in a crypt at the Cypress Hills Cemetery in Queens, New York. But the location remained unknown until 1959, when two Polish-Americans who were visiting graves at the cemetery saw a small marble plate with the inscription “Ignacy Jan Paderewski, 1860-1941.”

For an excellent account of the mystery of Paderewski’s heart, read Danuta Piatkowska’s article.

We had a competition to see where to put the heart. I thought it should go to Chicago. Paderewski loved Chicago. But there was a very enterprising young Monsignor at the Lady of Częstochowa in Doylestown, PA, and the heart went there.

The Paderewski Scholarship Fund: 2004 – present

In the 1990s, Rowny worked on a project he called a “living memorial,” for U.S. students to go to Poland and Polish students to come to the U.S. to study international relations.

The young people I talked to knew nothing about Paderewski. He’d been expunged from textbooks because he believed in democracy. I spent an awful amount of money and time and went bankrupt on it. I gave it up.

In 2004, I said, let’s do something else on a more modest scale. Let’s have Polish students come to the U.S. for a semester of study at Georgetown University. I paid for the first scholarship out of my own meager savings – $7,500.

Then I turned my rolodex and files over to the Fund for American Studies. They administer my scholarships. There have been 8 since then, the 9th is coming up this year.

Some of the older people who were giving have died. I had a benefit concert on February 11 and made enough money for this year.

Aneta Popiel, the winner of the 2008 scholarship came back [to the U.S.] for a Master’s Degree. I’m trying to find ways to help her pay off her debt. She can’t get a student loan as a foreign national.

I’ve asked her to help to establish a Paderewski Scholarship Alumni Association in Poland. One of the things I want to try is for the Alumni Association to sponsor programs in schools in Poland that teach about Paderewski – how he was the father of modern-day Poland, that he believed in true honesty in government, in school, in life.

Why Paderewski?

He’s the father of modern-day Poland. He’s the George Washington. In World War I, Paderewski was already famous [in the U.S.] – in 1890 he took the country by storm.

He was a great patriot and believed that one day Poland should be reunited. [Ed. note: Poland was under partition from 1795-1918.]

Paderewski with great patience and diligence and charm convinced Pres. Woodrow Wilson to put the 13th point [about Poland] into his 14 Points.

[After WWI], Paderewski went to Poland in 1919, stayed till 1921. His heart wasn’t in politics, he went back to the stage. Until World War II.

Paderewski went to Franklin Roosevelt. Now – he’s a sick man in 1939, but he convinced Roosevelt that the U.S. should prepare for war. The U.S. at that time was isolationist and didn’t want to go to war.

That’s my passion for Paderewski – plus the fact that he had a sterling character. Pres. Wilson called him one of the most honest men he ever met.

The General and Me: March 11, 2012, Maryland

Near the end of our conversation, the General asks about my background. This is rare for an interviewee. He also gives me a copy of his book, It Takes One to Tango, and thanks me for my interest in Paderewski. He then asks if I can help him with his walker out into the living room – his health has been good, he says, but he had a fall in August.

As he settles himself into a chair, he turns to me and says, “My grandmother used to say, Starość nie radość [Old age is not happiness].”

I ask, “Is that true?”

He says, “it is.” But with a smile on his face. CR

Imagery

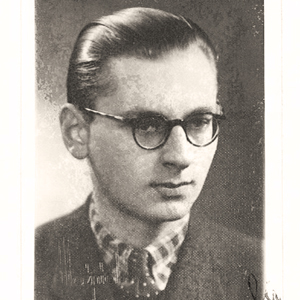

- Official portrait of Edward L. Rowny as Army lieutenant general; U.S. National Archives

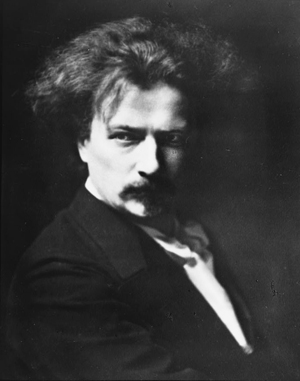

- A young I.J. Paderewski with his characteristic lion’s mane of hair; U.S. Library of Congress archives; photoprint by Arnold Genthe.

- An excerpt from President John F. Kennedy’s speech delivered for the Paderewski Ceremony at Arlington National Ceremony, May 9, 1963; JFK Presidential Library. Read the full speech.

- A June 26, 1992 Associated Press article excerpt: “Poland will hail Poland’s remains.” The caption reads, “Former Ambassador Edward Rowny holds a photo of Ignacy Jan Paderewski.”

SIDEBAR: 2008 Paderewski Fund Scholarship Recipient: Aneta Popiel

Aneta Popiel, who received a scholarship through the Paderewski Scholarship Fund in 2008, is back in the U.S. studying for her Master’s of Public Policy at Georgetown University in Washington, DC. She spoke at a February 11, 2012 fundraising concert about what that scholarship meant to her:

“Those 10 weeks over 3 years ago were one of the turning points in my academic and professional life. During this time, an exceptional faculty created for me and my fellow students space to involve in academic discourse on democracy, philanthropy and volunteerism.

“The summer program involved us in philanthropic work in the Washington area. I facilitated volunteer camps for young Americans who served the homeless in the country’s capital.

“The Paderewski Fund is the only scholarship in Poland which allows students to spend the summer studying in the United States.

“I am proud to be the Program’s Alumni and proud to fulfill the duty that was put on the grantee’s shoulders. It will only take a little time as the result of our actions will be visible in politics, business and charity in Poland. I hope you will have a chance to follow it.”

– Aneta Popiel

That was sooooo interesting.

Piekny zostawił nam w Polsce w Warszawie,ogród, za jeziorkiem “Wedlowskim”przy ulicy Zielenieckiej “Park Ignacego Paderewskiego” Biegałam w nim dużo jako, dziecko,najmilsze wspomnienia, dziecięcych lat.Jego imię zawsze wymawiane jest z dumą.Mielismy wielu wspaniałych postaci , kochali kraj i robili to bezinteresownie – z miłosci do Ojczyzny , ktorą prawdziwie kochali.

Dziękuję Panie Równy za poruszone wspomnienia. God bless You!

Mowie o ogrodzie Ignacego Paderewskiego

Irena Tomala P.

Przeczytałem ostatnie karty z ksiazki generala “Tango z niedzwiedziem” zatytulowane KU PRZYSZLOSCI POLSKI. Zadne z tych slow nie utracilo swojej wartosci i znaczenia. 5 sfer: przebudowa struktur politycznych, wzrost gospodarczy, naprawa sadownictwa, przywrocenie honoru i uczciwosci w kazdej dziedzinie zycia, przebudowa systemu oswiaty. Napisal to w 2006 roku, a w 2014 jest to nadal aktualne. Nawet widac to jeszcze bardziej.