Hacienda Santa Rosa today

Courtesy of Piotr Piwowarczyk

On July 1, 1943, a weary group of Polish refugees arrived in Leon, the capital of Guanajuato, Mexico, the final destination of a harrowing 20,000 km odyssey, including a six-week ocean voyage. As their train pulled into the station, they stared out the windows, puzzled by the sight of red and white decorations, the flags of Poland and Mexico, and the well-dressed and excited group of people – a delegation? – waiting on the platform. Expecting a distinguished guest? The train stopped, the passengers lined up to disembark. As the doors opened, a small orchestra began playing the Polish national anthem, and the welcoming delegation, headed by the mayor but also including a number of women who spoke Polish, greeted them with words of welcome and warm embraces. Stunned, the Poles burst into tears.

Anna Zarnecka de Burgoa

Courtesy of Piotr Piwowarczyk

Anna Zarnecka de Burgoa (photo at right), who was a part of this transport, recalls the emotions of that day:

“It was something incredible. After two years spent in the Soviet Gulag and later in refugee camps in Iran and India, for the first time we felt like human beings. Until now, we were unwanted trespassers, who bring with them illnesses and suffering. Here, they met us as awaited guests, and it is hard to describe the feeling of appreciation and surprise we all felt for their hospitality”.

From the Gulag to Mexico

Their journey had begun in 1940 with the forced deportation from their homes in Poland to exile in the Soviet gulag. There, forced to work in labor camps or on collective farms, they suffered from abuse, disease, cold, and starvation, and the death rate was staggering.

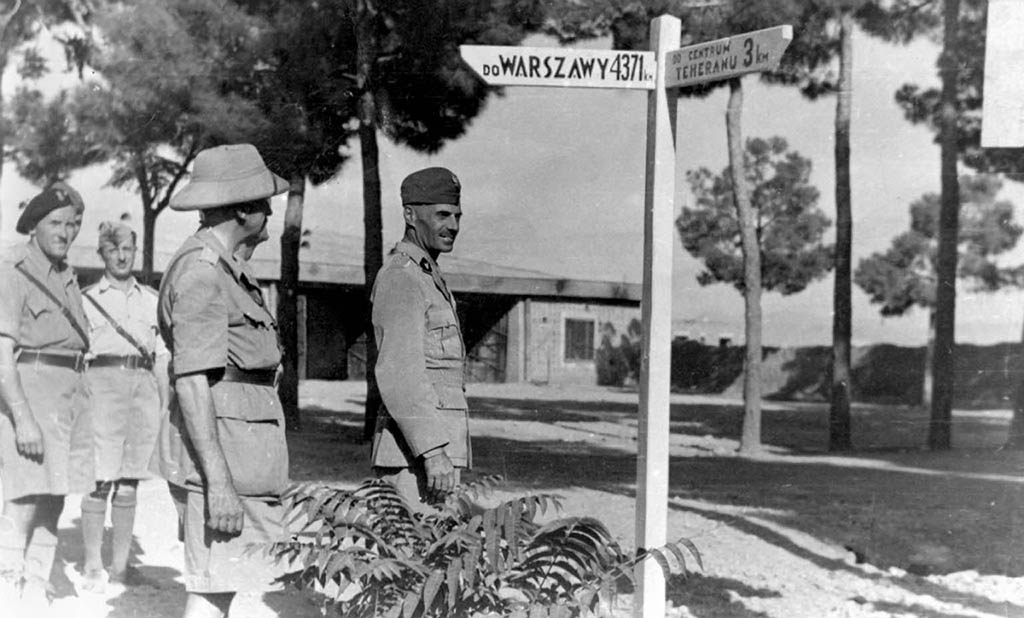

It was not until Hitler’s attack on his erstwhile ally in June of 1941 that the Polish deportees finally saw a ray of hope. Unable to withstand Hitler’s forces on his own, Stalin had no choice but to enter into an alliance with the West, and a condition of this new alliance was the release of his Polish prisoners and the formation of a Polish army. Although Stalin officially complied, he also made things difficult, including inadequate delivery of rations, medicines and equipment. Under the circumstances, General Anders demanded that his army be evacuated from the Soviet Union to the Middle East to fight under British command. Pressed by the British, the Soviets agreed but General Anders then demanded that the civilians, the women and children who had managed to reach the Polish army for protection, be allowed to leave with him. Leaving them behind would mean almost certain death for them and a serious blow to his men’s morale.

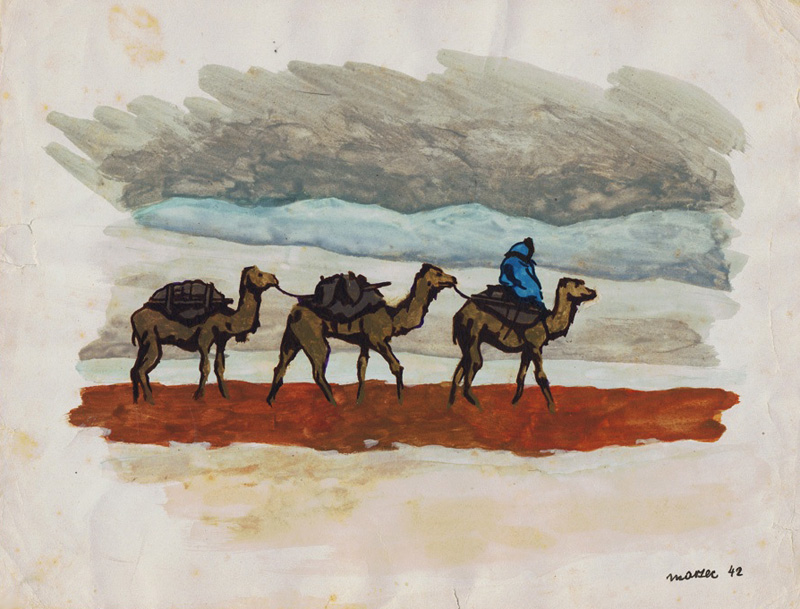

During the summer of 1942, some 56,000 civilians managed to leave the Soviet Union and cross into Iran, some in truck convoys over the mountains, the majority on crowded ships and barges across the Caspian Sea.

Among the evacuated children who eventually found their way to Mexico were Chester Sawko, whose grim memory included carrying his little brother’s body to a makeshift morgue at a railway station. Another child refugee, Stella Synowiec, saw her mother for the last time when her train in Russia left without warning after her mother had got off in search of food.

As Zarnecka de Burgoa recalls, leaving that “inhuman land” was like having life restored. Still, they could not stay in Iran for long. It was a hotbed of intrigue, the German forces in nearby Crimea, the Soviets not favorably disposed towards Poles.

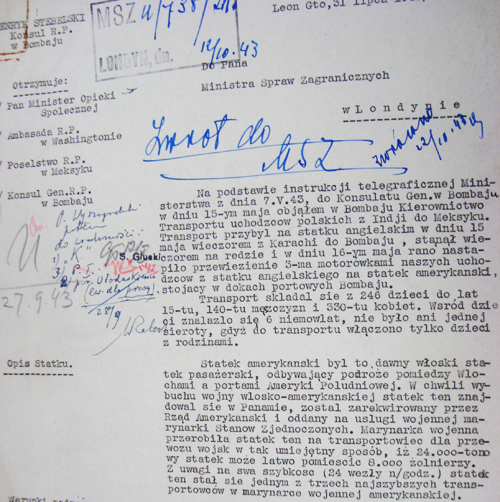

Polish Foreign Ministry document about Hacienda Santa Rosa and the refugees

In search of safe havens

In a world at war, safe havens were scarce, mostly in the Commonwealth countries, at first to India, then on to Africa and New Zealand. One surprising offer, however, came from Mexico.

In 1942, General Sikorski met with President Roosevelt in Washington hoping for support against Stalin’s aggressive policies. He was disappointed; Roosevelt, like many of his advisors, favored the Soviet Union much more so than Poland.

Sikorski’s despondent mood got a lift, however, by an invitation to visit Mexico, an initiative of Alfonso Rozenzwieg Diaz, the Mexican ambassador to Britain. Diaz, who admired Sikorski, pressed his country to accept some Polish refugees, an initiative supported by the Americans with a $3 million loan to be repaid by the Polish government after the war. Mexico thus became the only non-Commonwealth country to offer shelter to Polish refugees, a haven far enough away to reassure President Roosevelt that the Poles’ stories of the gulag would not annoy Stalin, something Roosevelt was loath to do. President Manuel Avila Camacho, for his part, proclaimed that his offer was in the spirit of Mexico’s traditional immigration policy “open to all enemies of totalitarian and fascist systems.” In reality, the Mexican decision to accept Polish refugees had no precedent in recent Mexican history, where legal immigration from non-Spanish speaking countries had been virtually abolished. But, having joined the Allies in May 1942, President Avila claimed that accepting the refugees should be seen as Mexico’s contribution to the Allied war effort.

Four months later, on April 5th 1943, a new Polish Ambassador, together with his British and American counterparts and the Mexican Foreign Minister chose a dilapidated hacienda called Santa Rosa, just outside of Leon, as the site for the future camp for 2,000 Polish refugees. The climate, not unlike that of the Tatras, was ideal; and being 10 km away from Leon, it would also prevent Polish-Mexican mingling. The Polish government-in-exile was to pay $10,000 a month rent, using funds from the American loan.

Meanwhile the Polish refugees waited in temporary camps in India. When the Mexican offer came, it was welcomed by British and Polish authorities but the refugees were understandably anxious about another extremely long journey to an unknown place. Finally, on May 13th 1943, the first group of Poles embarked on the two-day journey from Karachi, (then in India, now in Pakistan) on the British vessel ”The Old City of London” to Bombay (today Mumbai). There they transferred to an American passenger ship, “The Hermitage” and set off on their perilous 6-week voyage to Los Angeles, escorted by American war ships.

A strange American interlude

The next part of their journey can only be described as surreal. Having gained their freedom, the refugees arrived in America, a place that in their minds was freedom itself. But to their utter amazement, as they got off the ship, they were immediately put on military trucks and taken to a nearby internment camp holding Japanese Americans. The Poles noted with misgivings that their own section of “Santa Anita” was enclosed by barbed wire. They felt like prisoners again. Better conditions than in the Soviet Union but certainly not the America of their dreams. After four days, they were loaded onto military trucks again and taken to a train under military guard that remained posted at every door throughout their journey of some seven hours. The windows remained sealed, and no one was permitted to leave their coaches.

Finally they crossed the Mexican border where they boarded another train. And suddenly the guards disappeared. They were allowed to open the windows. They were free to wander from one compartment to another. They were in Mexico. They were free men, women and children on their way to their new home, Hacienda Santa Rosa. When the next group of 728 refugees arrive on November 2, Mexican railway workers were on strike, but as a gesture of solidarity, they let the train go through.

Historical photos of Hacienda Santa Rosa courtesy of the Kresy-Siberia Virtual Museum, Julian Plowy Collection

Hacienda Santa Rosa

The Santa Rosa Hacienda, completely renovated and freshly painted, had living quarters for families and a dining room, while the old mill building was transformed into a new school and an orphanage for 230 children. There were flowers gardens, ponds, and a playing area for the children.

Despite a lack of teaching materials, by August primary and secondary schools started teaching the full Polish curriculum, along with a class in Spanish. Felician sisters arrived from the United States to help care for the children, and Polonia charity organizations showered the children with gifts. The Polish War Relief Fund, with the National Catholic Welfare Conference, provided funds for education, healthcare and clothing and also sent books from New York for a Polish library. The community soon started cultural activities including scouting, theatrical performances, and concerts.

Historical photos of Hacienda Santa Rosa courtesy of the Kresy-Siberia Virtual Museum, Julian Plowy Collection

Although contacts between Mexicans and the Polish refugees were at first officially discouraged, the warm welcome and natural curiosity about so many blond, blue-eyed newcomers led to good relations between Poles and Mexicans. Noting the positive developments in the refugee colony, the authorities built a Mexican school adjacent to Santa Rosa and paved a road to connect the city and the hacienda. The new road meant the old tramway pulled by a donkey could be replaced by a bus donated by Polish Americans.

At first, the Poles were forbidden to compete with Mexican labor but in time, men and women opened small carpentry, tailoring, repair and other shops, which enabled them to use their skills and to relieve the tedium. As time passed, everyday life became routine, though everyone was conscious of its temporary nature and going home when the war ended. Unfortunately, the war’s end did not mean a safe return home since their country was given over to Soviet control, the very regime that had displaced them and brought them so much suffering in the first place. By the summer of 1945, the refugees in Santa Rosa officially had no home, and their government, the one that had done so much to find a haven for them, was no longer recognized by their allies and was unable to help.

Historical photos of Hacienda Santa Rosa courtesy of the Kresy-Siberia Virtual Museum, Julian Plowy Collection

What now?

In September 1945, a deputy of the Mexican president arrived in Santa Rosa to tell the refugees they were free to apply for departure documents from Mexico or to apply for an immigrant status in Mexico. A few weeks later by President Avila Comacho arrived and personally proposed that the Santa Rosa inhabitants remain in his country permanently.

In 1946, the Polish embassy was taken over by staff sent by the new Communist-controlled government in Poland. Their delegations to Santa Rosa failed to persuade all but a small minority to return to a communist Poland, and those few who returned did so only because they had spouses and children there who could never get permission to leave. During that final year the majority of the Poles in Santa Rosa chose to go to the United States. Among them was Chester Sawko who ended up in Chicago. Chester was drafted into the US Army and shipped off to fight in Korea. Upon his return he started his own business designing and manufacturing spring coils for the automobile industry. His business was very successful and within a few years Chester was a multimillionaire. He married Stella Synowiec, an orphan he met in Santa Rosa. Today Chester and Stella Sawko are engaged in philanthropic activities in the US, Poland and Mexico. In 2001 they visited Mexico to open a school and a clinic they helped to finance. “That’s how we pay our debt for everything the Mexicans did for us during the war,” they say. “We will never forget it”.

A small group remained in Mexico, mainly women who married local men. One of them was Anna Zarnecka who married Jesus Burgoa, a promising young businessman who later became very successful. They settled in Mexico City, where she established herself as a painter and was active in the Mexican Red Cross. Today in her early 80s, she lives surrounded by her sons and grandchildren, dividing her time between charity work, painting and writing her memoirs about Poland and her interesting life. The camp was officially closed on May 16th 1947, when the remaining refugees, still awaiting their departure papers were asked to leave. Some of them relocated to Mexico City, and some wandered as far as the Yucatan Peninsula. A group of 106 children and 99 adolescents who lost both of their parents in Russia were sent to an orphanage in Tlalpan where some of them remained until 1950 before going on to their adoptive Polish families or orphanages in the USA.

Commemorative plaque

Courtesy of Piotr Piwowarczyk

The group that settled in Chicago formed an association called “The Poles of Santa Rosa.” In 1993, they organized a 50th anniversary reunion and four years later they visited Santa Rosa, now an orphanage for boys run by the Salesian Fathers. There, they unveiled a commemorative plaque honoring their Mexican hosts for their hospitality and kindness.

Hacienda Santa Rosa had a profound influence on their lives. They cherish it as a place where they found peace and recovered from the physical and psychological wounds of war. They will never forget the traditional Mexican hospitality that enabled them to rediscover their dignity.

CR

Pingback: Uchodźcy z Santa Rosa | Santa Rosa

Terrific article. Thanks for sharing

My mother was also in Siberia but ended up after Persia in Palestine Egypt Italy and Britain before emigrating to NYC and lives the American dream

I am glad to see more of my parents peers stories being documented. At 80 theyve seen so many friends go before their stories were captured. Please preserve as much as you can.

My father in-law is trying to find out more about his history, if anyone has any info about him please email me!

Pietr Warenda or Peter Francis Warenda

I am trying to help him find additional info.

Looking for information in regard to him or his family history/relatives/Pedigree in Poland.

He possibly origionated from Minsk, Mazowieckie, Poland

Sept. 14, 1943 Bombay,India boarded the USS Hermitage

with other refugees.

Pietr Warenda, 7 year old student, orphan

Oct 24, 1943 arrived San Pedro, California

after disembarking was at Griffith Park Internment Camp

shortly after sent to Leon, Mexico to the Santa Rosa Orphanage

Any help greatly appreciated

Pingback: Once Upon a Time in Africa…

Pingback: February 1940: Exile, Odyssey, Redemption

I would like to know who was the first owners of the Hacienda De Santa Rosa. During the year 1850 thru 1940 , Thank you Ermida Esparza

Many thanks! I knew and revered Chester Sawko.

Pietr Warenda is listed on page #17 in my post of all refugees at Santa Rosa Mexico He came from Brodnica Pow Pinsk Parents Tadeusz and Maria

I met Wanda R Markgraf, one of the refugees that experieced that transition to Santa Rosa from Poland. I met her at a mass at Milwaukee an she related her story to me and to my wife who i a mexican national. I told her we go to Mexico often especially Leon, and I promised her that next time we visit Mexico, I would try and locate Santa Rosa.It so happens that my great uncle is a Salesan Priest an he was assistant retor at Santa Rosa in the 80″s. I discovered this info after visiting Santa Rosa in June 2015.I took pictures and will be visitng Wanda later this year( 2016) I would like to get a copy of the movie that was made and give it to her. Please tell me where U can purchase this movie so that she’ll be to see it. sincerely, JOSEPH RUIZ

Julian Plowy

I see in an earlier post that Pietr Warenda is listed on page #17. What article are you referring to? My father Henry Joseph Choma was also a refuge of Poland and has fond memories of Santa Rosa. I am looking for additional information. I would like to see routes from when the Polish refuges left Poland. My father ended up in Santa Rosa and his brother was in Africa. My dad was born 12.8.1931, his health has taken a decline this past year.

Thank you – Elaine Hayes

Janina Skawinskaa

My family was deported to Siberia from Hermanowice, Poland, on the morning of February 10, 1939. I was merely two years of age. I have yet to finish translating my mothers memoirs from that horrific time in our lives. We eventually landed up in Colonia Santa Rosa, Mexico. I was attracted to your comment about Pietr (more likely Piotr). My deceased mother, Karolina Skawinska worked as a caregiver to the male orphans. More than likely Piotr could have been one of them. Eventually, we made it to the US. When the Colonia ended many of the orphans found refuge in the midwestern US

My previous message was intended for Rachel Warenda.

I am using the experiences of refugees during WWII for my PhD project, does anyone have access to primary sources or any type of memoirs from individuals who lived in the camp they would be willing to share or discuss? I would deeply appreciate any assistance I can be contacted at jpredebon@yahoo.com

Joseph

listen to this talk, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WR2kKw3kQEA and look into the amazing story of Wojtek the Soldier Bear. His fans gather here on Facebook.

https://www.facebook.com/groups/wojtekthesoldierbear/

try here too

http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/13/a4171213.shtml

My father was in the Santa Rosa camp at age 7 as an orphan. No idea what happened to his family .

My Mother-in-law, her husband and 3 of their 4 childred were also sent to Siberia, then Persia, where her husband died, and she and her 3 children left from Karachi onto a warship (I believe

The Hermitage), we have one list but they are not listed and I was told that The Hermitage had made 2 trips. They landed in California but it was decided to send them by train to Mexico and then to Santa Rosa. Their names are printed on the memorial wall in Santa Rosa. In 1948 they came to live in Canada and in Guelph Ontario there were several families settled that were also in Africa. As being the wife of my late husband, I have a few pictures of his life in Santa Rosa. I also have a Report Card from Persia when he attended school there.

BRINGS BACK A LOT OPF MEMORIES

What a great story about polish refugees being in Santa risa and we’ll taken care by Mexico.

Thank you me

Pingback: Polish refugee woman from Russia as seen in American propaganda – Silenced Refugees

I was a young boy when my father Juan Coronado took me to his job site. this was it. the hacienda santa rosa in Leon Guanajuato , had such a good time while being there. by the way there were some underground tunnels there that didn’t seem to have an end.

Pingback: How U.S. Lied About Polish Refugee Children to Protect Stalin | Voice of America – 80 Years of Hidden History

Pingback: Polish refugee woman from Russia as seen in American propaganda | Voice of America – 80 Years of Hidden History

My fathers mother Mary Abramajtis sister Gosia Abramajtis and brother Albert Abramajtis were in camp in Santa Rosa Mexico

My father was in school in Egypt after Siberia.

Hello: My Mom, Genevieve Kowalska Bartyzel was at Santa Rosa. I have her diary, written in Polish. I’m going to have it translated so we, her family, can read of her trials and tribulation as a Polish Deportee of World War II.

Hello

My mother, Henryka Oszust, born January 1935 was at Santa Rosa, as a polish refugee. Her twin sister Maria and her were separated in Siberia.

I have been to Leon in 2000. I was a stock broker and volunteered to meet a Mexican client in Leon who was building homes in Cancun Mexico. While in Leon & Guanajuato (which as it turned out was the home of the artist couple Diego Rivera & Frida Kalo). Also, The town is known as a rich town of the silver trade. My Aunt Rita was one of the polish immigrant children. Later she moved with some of her family to Chicago. My Uncle Raymond Davies born in the coal mines in central Utah , and raised LDS met his beautiful Catholic wife from Poland byway of Mexico in Chicago. He was smitten and loved her his whole life. She wrote a wonderful story of her Polish upbringing and during the hard times in Russia; and then her times in Mexico; and her humble times in Chicago.

To the author Piotr –

Would you have any information on how to contact the group, “The Poles of Santa Rosa” – I wish I had known of this group in Chicago before I moved to California. Would like to see if anything is going to be done this year as it will be the 80th anniversary. Thank you