There have been a number of women woven into the fabric of Americana for their freedom fighting. Stories of ‘Molly Pitcher’ (Mary Ludwig Hays McCauley) who kept the Continental troops hydrated at the Battle of Monmouth, bringing them water under fire and even taking up the rifle of her fallen husband, show the strength of Revolutionary women. Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman who wrote under the pen name ‘Nellie Bly’ is respected in both the journalism and mental health communities for her undercover exposés of the deplorable conditions at asylums. Mary Harris ‘Mother’ Jones, an immigrant from Ireland, represents the protective maternal drive that inspired many significant labor struggles during the Industrial period.

There have been a number of women woven into the fabric of Americana for their freedom fighting. Stories of ‘Molly Pitcher’ (Mary Ludwig Hays McCauley) who kept the Continental troops hydrated at the Battle of Monmouth, bringing them water under fire and even taking up the rifle of her fallen husband, show the strength of Revolutionary women. Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman who wrote under the pen name ‘Nellie Bly’ is respected in both the journalism and mental health communities for her undercover exposés of the deplorable conditions at asylums. Mary Harris ‘Mother’ Jones, an immigrant from Ireland, represents the protective maternal drive that inspired many significant labor struggles during the Industrial period.

These women, and countless others, nurtured the American dream by fighting for freedom in distinctive ways. The coalfields of northeastern Pennsylvania also produced one of these remarkable women, Mary Septak, although her story is often forgotten.

Like Mother Jones, Septak too was an immigrant who organized labor protests.

She is invariably identified as “Slavic,” rather than by any specific ethnicity, and her fluency in many of the Slavic languages suggests this was apt. She was known for her fiery speeches to all of those ethnic groups and her personal preference seemed to be inclusive, rather than narrowly nationalistic. She was well aware that they were all united in their grim poverty, and all subjected to exploitation and discrimination.

Septak lived in Lattimer, a coal patch outside Hazleton, Pennsylvania. Like many other wives of coal miners, whose salaries alone could not support a family, she operated a boarding house. In fact, without additional income a miner would often become indebted to the coal company for his cost of living compared to the salary paid.

While the U.S. Constitution is a shining example of partnership and consent in both its creation and execution, the laws developed to protect miners were not. Miners were, in effect, indentured servants to the coal company. After receiving a meager wage, they were charged rent for their home, owned by the company, had to buy supplies and food at the company store, and received services, such as they were, from the company physician. Saving for, or owning, any property was impossible, and a lifetime of work left miners indebted to the company.

In order to make enough money to sustain a family not only did wives have to work but so did children. Boys often left school before the age of ten in order to work for a few cents per day picking slate and other unburnable rock from coal dumped by mule-driven cars. These ‘breaker boys’ who worked in a cloud of soot, often resorted to chewing tobacco beneath their handkerchief facemasks so they could tolerate their condition.

Once a boy was old enough he could ascend the corporate ladder to mule handler and eventually miner. When a miner could no longer fulfill his duties he would return to where his career began, sitting alongside breaker boys in an attempt to collect some pay for his family. This is the origin of the regional phrase: “Twice a boy, once a man.”

Septak watched too many men return to the ranks of boys, if they were lucky and did not die in the mines. She saw too many of her friends dealing with the trauma of these untimely, preventable deaths. This Slavic immigrant, who was literally and figuratively larger than life, boldly stood up for the American dream. ‘Big Mary’ organized demonstrations, and exhorted the miners to join a union, the United Mine Workers of America.

Big Mary’s powerful speeches, shifting from one Slavic language to another, enabled her to unify otherwise feuding Poles, Slovaks, Lithuanians and Russians.

Big Mary’s powerful speeches, shifting from one Slavic language to another, enabled her to unify otherwise feuding Poles, Slovaks, Lithuanians and Russians.

Coal companies were used to fighting Western European immigrant strikers, but Big Mary unleashed an Eastern European immigrant front that confused King Coal. After all, coal barons like J.P Morgan had actively recruited these Slavic miners as strikebreakers.

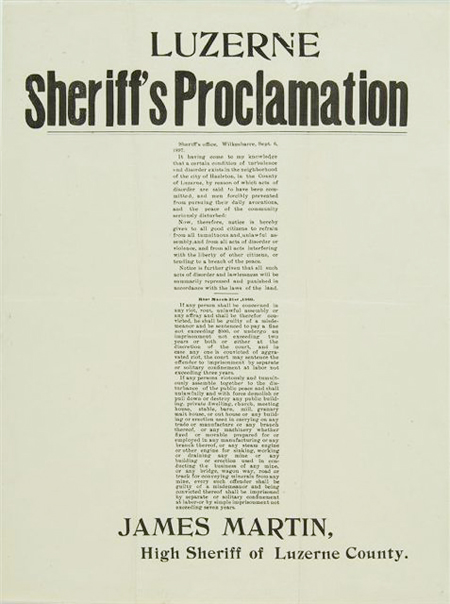

On September 10, 1897 Big Mary led a group of her strikers to the Lattimer Mines. The peaceful demonstrators, mostly Polish, Slovak, and Lithuanian anthracite miners, encountered Luzerne County Sheriff James Martin and his improvised posse. After a scuffle with the unarmed demonstrators the miners were ordered to march around Hazleton – not through it.

The sheriff’s posse then took a trolley to Lattimer in order to head off the marchers. One deputy was overheard saying “I bet I drop six of them when I get over there.” Martin’s men met the nearly 400 marchers outside Lattimer, ordering them to disperse. Martin even attempted to wrestle the American flag from the hands of the lead marcher, Steve Jurich’s. When one of the sheriff’s men yelled “Fire!” Jurich was the first man to fall. The dead and injured fell, shot in the back, some bodies falling over others. In total 19 were killed, 32 injured as they fled into a nearby school. According to one report, an injured man cried out for help, to which a deputy responded, “We’ll give you hell, not water, hunkies!”

In 1898, Sherrif Martin and his deputies were brought to trial in the Luzerne County Court House in Wilkes-Barre. All were acquitted.

In 1972, a memorial plaque was erected in Lattimer with these words:

“It was not a battle because they were not aggressive, nor were they defensive because they had no weapons of any kind and were simply shot down like so many worthless objects, each of the licensed life-takers trying to outdo the others in butchery.”

However, Big Mary Septak emerged bigger than ever and was able to gain the attention of Mother Jones who added her voice to the labor dispute. Even President Theodore Roosevelt paid attention to the misery in the anthracite coalfields of Pennsylvania. As a result, following commissions involving such names as J.P. Morgan, Clarence Darrow and former President Grover Cleveland, some concessions were made by coal companies.

These concessions forged Roosevelt’s progressive reputation toward unions, enhanced Darrow’s prestige as a councilor, Morgan’s standing as an arbiter, and Mother Jones as a popular icon of labor. However, had Septak not united the Slavic miners of the Anthracite Coal Region, all of these American icons would shine a little less brightly. ‘Big Mary’ helped nurture a movement of new things in America.

Coal companies often resorted to assigning miners to teams in which no one was the same ethnicity. This was not an attempt at cosmopolitanism, but rather a scheme to discourage communication to prevent miners from socializing and form ing unions. Mary Septak made us of all languages to unite Slavic miners under one banner – the American flag.

A century later the ethnicities have changed but the dynamics remain. Just as the Americanized Irish and English were suspicious of Slavs with their religious culture and strange languages, today in Hazleton it is the Americanized Slavic community that distrusts immigrant Latinos for those same reasons. “War in Hazleton: Main Street Meets the Global Village” is the subject of one course at Temple University in Philadelphia. A lesson for all ages. CR

Imagery

- Proclamation by Sheriff Martin, Sept. 6, 1897, warning against “unlawful assembly” and printing the riot act.

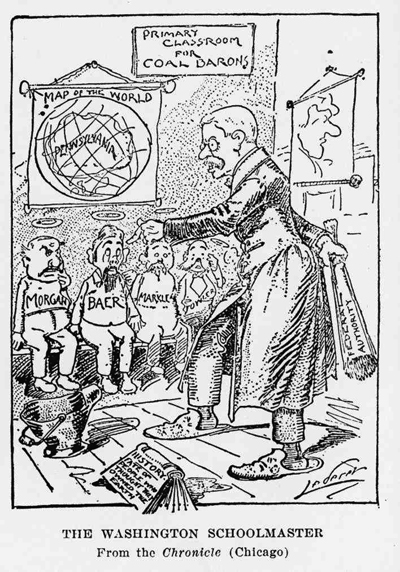

- This 1902 cartoon was published after remarks from Phildalephia and Reading Railroad president George Baer, “”These men don’t suffer. Why, hell, half of them don’t even speak English,” US President Theodore Roosevelt teaches the childish coal barons a lesson on the importance of Pennsylvania coal.