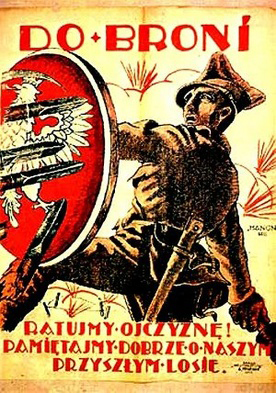

A Polish poster from the Polish-Soviet war era: “To Arms – Save our Motherland! Think of our future.”

Quick: Name some of the most important battles of the world – ancient, 20th century, current day. (No Googling!)

You might come up with the Battle of Stalingrad or the Invasion of Normandy.

Perhaps Waterloo: 1815 or Vienna: 1683.

Central America: 1521, the Siege of Tenochtitla: Cortez conquers the Aztecs.

Further back: The Battle of Badr in 624, which significantly impacted Islam’s formative years.

Even further back: Battle of Cannae, 216 BC, Hannibal annihilates the Roman army.

Closer: The Tet Offensive in Vietnam. The 2003 Battle of Baghdad.

But what about the 1920 Battle of Warsaw?

Fought on the heels of World War I, this pivotal battle of the 1919-1920 Polish-Soviet War stopped Bolshevik armies from advancing west, established an independent Poland – and set the stage for Stalin’s brutality towards the Polish nation during World War II.

2010 marks the 90th anniversary of the battle. And August 15th marks the battle’s most pivotal day.

In August, I received an email from my editor at CR. She’d sent me Encyclopedia Britannica’s “On This Day” newsletter for August 15.

The newsletter included the establishing of the Panama Canal in 1914; Bahrain’s 1971 independence from Great Britain; Congo’s 1960 independence from France; Napoleon’s 1769 birth, and Macbeth’s 1057 death. No Battle for Warsaw.

She asked whether I’d like to write on this topic. I did indeed. And so I reached out to historians and experts, researched and read. I learned about the battle’s offensive, its global implications, and how Polish cryptographers contributed to the Polish army’s victory. There are current-day implications stemming from the battle; I learned about those too.

I contacted the encyclopedia – and had a very cordial email correspondence with their communications director.

And I also learned that this battle is a huge deal.

Let’s begin.

Polish soldiers, 1920

Battle for Warsaw: “The 18th Most Important Battle in the World”

“Everybody quotes viscount D’Abernon, a British lord who was writing about military battles and called that battle the 18th most important battle in the world,” said John Micgiel, East and Central European expert and Columbia University professor.

D’Abernon was part of the 1920 Interallied Mission to Poland, and wrote The eighteenth decisive battle of the world: Warsaw, 1920 in 1931.

“How he got to that is anybody’s question,” Micgiel said. “Why 18th and not 19th or 17th?”

But according to Micgiel, there’s no doubt that the battle is significant: It not only established an independent Poland but also prevented the Bolsheviks from moving into Western Europe at a time when Vladimir Lenin saw Poland as the first step of spreading communism westward.

Bolshevik Soviet Commander Mikhail Tukhachevsky wrote in his order of the day on July 2, 1920: “На Запад! (…) Через труп белой Польши лежит путь к мировому пожару” – “To the West! Over the corpse of White Poland lies the road to worldwide conflagration.” He used the term “White Poland” to contrast it with red Soviet Russia. Conflagrations means a huge fire. (I had to look it up.)

Historian and Harvard Professor Emeritus Richard Pipes, who wrote about the battle and its consequences extensively in his Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime, told me that “the defeat in Warsaw persuaded [Lenin] not to send Soviet troops abroad anymore.”

And that saved Europe from possible Soviet intervention in the years that followed. “It was a very important victory,” Pipes said, adding that although the Soviets did intervene in Europe afterward – they did so through local Soviet parties, not by military means.

“They did not send troops into Europe anymore after that,” he said.

Encyclopedia Britannica: On This Day in 8/15: No Battle for Warsaw

When I contacted the encyclopedia with an interview request, Director of Communications for Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc. Tom Panelas, responded and asked for some clarifications on my project.

Once I explained, he wrote that content for the newsletter “comes down to the judgment of the editors, and they weigh a number of different factors in deciding, some of which is what other notable events took place on that day, what they think our readers would be most interested in, whether events similar to the one in question, or in that location, have been included recently, and so on.”

He also wrote that he would forward information about the battle to the editors, “and ask that they consider it on its anniversary next year.”

Polish artist Wojciech Kossak’s “Miracle on the Vistula,” painted in 1930. Mary is depicted at top left.

Omission, Controversy and a Miracle

I asked Keely Stauter-Halsted, the new chair of Polish history at the University of Illinois at Chicago, what she thought the significance of the omission might be. And not just the omission of this, but other Polish events: The Warsaw Uprising’s anniversary came and went on August 1 without mention in the encyclopedia’s newsletter.

“I would somewhat tentatively say two things,” she wrote in an email.

The first is that “a half century of being hidden behind the iron curtain in the ‘other Europe’ has led educated people – journalists, teachers, ordinary thinking people – to discount events throughout Eastern Europe and treat them as somehow separate and not connected to wider historical developments.”

But, she wrote, these events do have “wider meaning.” And as such, “They should be understood and studied in a broader context, especially now that Poland has officially re-entered European and world affairs.”

And even in Poland, the battle, known as “Cud nad Wisla” – “Miracle on the Vistula River” – is not without controversy.

Two factors contributed to the battle receiving that nickname. The pivotal day of the battle, August 15, occurred on the Catholic holiday of the Assumption of Mary and the battle was indeed considered miraculous. But there was also a political campaign in the period between the two World Wars in Poland to take credit away from the battle’s commander – Marshall Pilsudski – and Gen. Jordan-Rozwadowski, who came up with the battle’s strategy, according to John Micgiel.

“That’s why this ‘Cud nad Wisla’ comes up,” Micgiel said, “and it’s a misnomer. It’s really difficult to put the credit with the Virgin Mary when you have so many people fighting on the ground.”

Pilsudski’s political opponents tried to take credit away from him for that battle, Micgiel said: “But the bottom line is that it was Pilsudski and his troops that won the war.”

How Miraculous and Miraculous How?

First, there’s the numbers: The Soviet army was estimated at 1.4 million. The Polish army – at 700,000.

Soviet losses are estimated at 10,000. Polish losses are estimated around 4,400.

There’s more.

Mark Kramer, director of the Harvard Project for Cold War Studies, said: “Most observers at the time had concluded that Soviet Russia was on the verge of defeating Poland and being able to reclaim the territory in that area.”

But that battle changed the tide of the entire war. And, in turn, the war limited an effort by the new Bolshevik regime in Russia to expand to the territory of the old tsarist state, Kramer said. As the Bolsheviks took power in Russia in 1917, the new regime “ceded a considerable amount of territory,” he said. After World War I, the regime decided it was going to try and reclaim some of that lost territory and expand even further.

“And so Poland’s defeat of Bolshevik expansion at this point basically forced the Soviet configuration that had been laid out at the end of the first world war,” Kramer said. “And that was still a very, very large country – but smaller than it had been prior to 1914.”

Józef Piłsudski

Polish Victory; Soviet Defeat

Kramer called the battle a “classic laying of a trap by Pilsudski for [Soviet Bolshevik commander] Tukhachevsky’s forces.” Tukhachevsky was leading a broader attack into Poland and marching on Warsaw. He’d taken precautions for possible Polish counterattacks with one major exception – and that was in the South.

“Which of course is precisely where Pilsudski was marshalling his own forces and putting up very little resistance to Tukhachevsky’s advance,” Kramer said.

As Tukhachevsky neared Warsaw, Pilsudski found a large opening in the south of Tukhachevsky’s forces. Pilsudski moved in “with a devastating counterattack and basically annihilated Soviet forces in very short time,” Kramer said. “It was a complete defeat for the Soviet forces and changed the tide of the war and led to Poland’s ultimate victory in that war.”

Polish Victory; Stalin’s Revenge

The Polish victory consolidated Poland as an independent state and a leading country in Europe during the interwar period, Kramer said. Poland hadn’t existed as a state since 1792 when it was partitioned by Russia, Prussia and Austria, regaining its independence after World War I.

The victory had another crucial consequence, one that impacted millions of Poles decades later during the Second World War.

“Stalin looked back on the 1919-1920 war with Poland as something he wanted to reverse and to gain revenge for,” Kramer said.

That revenge partly lay behind the “brutal Soviet occupation of Poland in 1939 – June 1941,” he said.

Stalin was also concerned that Poland would join with other powers – Britain, Germany, Japan – in trying to encircle the Soviet Union. Kramer said that this particular concern is questionable: “Stalin had a lot of suspicions and fears that were not well-founded.”

There’s no doubt, however, based on archival evidence, that Stalin was convinced that Poland would seek to join with other countries to destroy the Soviet regime, Kramer said.

“That was again largely a consequence of the 1919-1920 war,” Kramer said. “Had Poland not won that war it never would have been seen by Stalin as a country to worry about.”

And So

I recently watched an animated history of Poland, created for the Polish Pavilion at the Shanghai Expo 2010. This eight-minute piece showcases Poland from 800 onward – and moves fluidly from battles through wars and uprisings, artistic and scientific achievements. It’s all woven together with maps of ever-expanding and contracting Polands throughout the centuries.

And there, about five-and a half minutes into the movie – right after 1918 and the end of the First World War – is the Polish-Soviet War and the Battle for Warsaw. A broad-shouldered, mustachioed Pilsudski strides up to a Soviet soldier; in back of them, a map shows a flood of red entering Poland, on its way to Europe. Pilsudski stares at the soldier; in an unexpected moment of levity, Pilsudski brings his hands up and cracks his knuckles, as if to say: “Bring it on.”

And then there’s the battle. It’s less than five seconds. And if you didn’t know about the battle and war, you may miss it – or think it’s an extension of World War I.

But I didn’t miss it, because I now know: I know the battle’s significance. I know how it turned the tide of a war that stopped Lenin’s armies, saved western Europe from communism, how it established an independent Poland and how it set the stage for Stalin’s revenge in the years to come. I hope, too, that the Encyclopedia Britannica now knows the significance of honoring August 15th. And on that day in 2011, I hope that the many subscribers to their On This Day newsletter will know as well.

Further Reading

Cryptology

The latest development about the battle, according to Mark Kramer, occurred thanks to recently declassified documents from the Polish-Soviet war. Those documents, he said, show that Polish cryptographers were able to read Soviet-encrypted communications from 1919 on.

“That certainly contributed to Pilsudski’s victory,” Kramer said.

But even if Pilsudski hadn’t been able to know that Tukhachevsky was going to be pressing forward, Pilsudski undoubtedly would have taken the same approach.

“It’s not to say that it drastically changed Pilsudski’s strategy,” Kramer said. “I don’t think it did. But what it did was give him a high level of confidence that it would work.”

Kramer also said that the development of cryptology in Poland was “about as advanced as you would find in the world at this point,” and that Polish cryptographers also contributed significantly to the Ultra operation that broke the Enigma code.

“It still is unclear why it took so long to have [the documents] declassified,” Kramer said. As a general rule, cryptological secrets often are very highly classified, he said – but materials from the later World War II were declassified long ago.

The Battle for Warsaw Today: Ossow

The heaviest fighting of the battle occurred in Ossow, a small town on the outskirts of Warsaw, and 22 Bolshevik soldiers are buried there. Earlier this summer, the Polish government decided that these soldiers should have a military burial. A memorial was built and a ceremony was planned; the Russian ambassador was to attend. But locals protested and Home Army veterans said they wouldn’t participate because honoring Bolshevik soldiers was scandalous.

“And so rather than consecrate this memorial in the middle of this controversy, the Polish government decided to just lay low for a while,” Micgiel said. According to local reports, protestors chanted “shame” during a demonstration, and the monument was painted with red stars.

“Not everybody today is aware of what happened in 1920,” Micgiel said, but they’re aware that Bolshevik soldiers are buried there and say they shouldn’t be honored. Local reports say that the ceremony has been postponed indefinitely.

“So 1920 comes back to haunt the Poles a little here,” Micgiel said.

CR

Pingback: 2014: The Year of Anniversaries