The Kentucky Derby

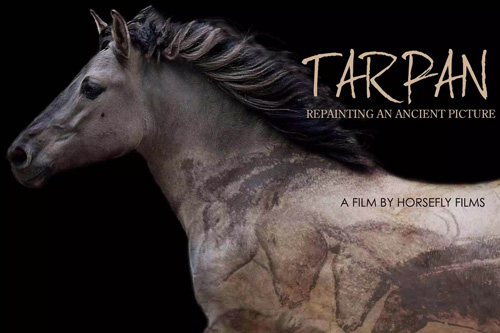

Photo courtesy of Kentuckytourism.com

“There’s Good Time Charlie! I haven’t seen him in years,” says Manny. “I thought he was in prison.”

I’m at the Churchill Downs race track in Louisville, Kentucky, experiencing my very first Kentucky Derby and wearing a hat with large red flowers. Thus far, I’ve downed the obligatory mint julep; explored the enormous infield; placed a single, tenuous bet (and lost); admired elegant horses being led onto a track for the day’s second run; watched a few races on a massive screen; and met a vibrant cast of Derby characters, including Good Time Charlie – a middle-aged man with blond shoulder-length hair, expensive-looking jeans, and gold cowboy boots.

As he saunters over to chat with a man sitting next to me, Manny, a Derby regular, greets him with a wistful, “You look good, Charlie.”

A complete Derby novice, I knew little about the event when I arrived in Louisville a day ago. I’ve had a crash course on all things Derby since then, as the city lives and breathes little else during the two-week-long Kentucky Derby Festival, which culminates in Derby Day.

The official Kentucky Derby is only one of the races run on Derby Day, held annually on the first Saturday of May. The first Derby Day was on May 17, 1875, during which a crowd of 10,000 cheered a horse named Aristides to victory in the mile-and-a-half (2.4 kilometer) featured race of the day, the Kentucky Derby. The race was shortened by a quarter mile in 1896 and has remained a mile and a quarter (two kilometers) to this day.

Throughout the years, the number of races on Derby Day has grown. In 1875, there were four. This year, the Derby will be the eleventh race of the day. The other races, while not as well-known as the Derby, nevertheless attract “some of the best horses in the country to try and capture some of the rich purse money” of the day, according to Derby enthusiast Sandy Lamp.

The Kentucky Derby race features three-year-old thoroughbred horses. The winner will be draped with a blanket of 554 roses – hence the race’s nickname, “Run for the Roses.” The race is also known as the “Most Exciting Two Minutes in Sports” because that’s how long it takes.

Derby fever’s easy to catch; at one point before the race I find myself telling a local, “Well, Desert Party undoubtedly has a great lineage, but he’s only ever raced in the heat of Dubai. I’m just not sure he’ll be able to pull through in this damp chill.”

The fact that I feel confident enough to express my opinion on a horse I knew nothing about less than 48 hours ago points to the all-inclusive nature of the Derby. It truly is an event for all – novices, experts, professionals, and those normally not inclined towards sports-watching, like me.

The names of the horses range from the poetic – “Regal Ransom” and “Friesan Fire” – to the decidedly less so, such as “Dunkirk,” and even ironic – “Chocolate Candy’s” owners are Sid & Jenny Craig of Jenny Craig Weight Loss Systems. I find “Pioneerof the Nile” particularly vexing: My grammar-obsessed brain winces at the lack of a space between “Pioneer” and “of.” The space can never be added, however, because the maximum number of characters allowed for a Derby horse (including spaces and punctuation marks) is 18. Hence, Pioneerof.

The eventual winner’s name, Mine That Bird, reflects his lineage from sire Birdstone and dam Mining My Own.

Betting is an important – some say the most important – part of the Derby. I’ve read about and been instructed in the plethora of betting possibilities: A trifecta means that the bettor has to exactly predict 1st, 2nd, and 3rd places. Even more daunting is the superfecta – predicting 1st through 4th places. An exacta calls for determining 1st and 2nd places; less confident bettors can also bet on a horse to “win” – come in 1st place, “place” – come in either 1st or 2nd, or “show” – come in either 1st, 2nd, or 3rd.

Throughout the day, the lines in front of the betting booths never dwindle. While we wait to place a bet, I listen to an older gentleman explaining bets to his small grandson, who is dressed in a cowboy shirt with jumping cartoon horses. The grandson looks like he understands as much about betting as I do, but also looks – as am I – absolutely thrilled to be here.

Our $40 infield tickets offer general admission into the main gate and the infield – which is an enormous field jammed with food, beverage, and merchandise booths. Since the infield is somewhat removed from the track, enormous screens placed at regular intervals offer close-ups of each race as well as scoreboards and statistics. We do manage to make our way to the edge of the infield fence to watch the start of one race. To gain admittance into the stands, which look down directly onto the racetrack, we’d need to pay hundreds more dollars in ticket fees.

The infield’s atmosphere is that of an outdoor festival and it’s a fantastic place for people-watching. Traditional Derby-wear calls for hats and dresses for the ladies and suits for the men. Many men wear seersucker suits, while most of the women wear dresses and heels with their hats. The hats range from tiny to huge – some are elegant; some garish; others are purely playful. Peacock feathers, fake and real flowers, bows, pins, sequins, and ribbons adorn hats in every color and manner imaginable. But not everyone wears hats or suits; the infield crowd is decidedly less dressy than the folks we glimpse in the stands and fancy V.I.P. areas.

Despite the vast number of spectators (this year’s Derby attendance is estimated to be around 153,500) the Derby doesn’t feel crowded. The venue is sprawling, and there are always places to move and escape the masses. By mid-afternoon, we’ve found a quiet(er) courtyard with benches and sit sipping our drinks, observing the throngs, and chatting with everyone around us.

19th century bourbon whiskey bottle from Gettysburg.

Photo by Gettysburg National Military Park.

Most folks are drinking mint juleps, the official drink of the Derby. Made with bourbon and simple syrup, the drink is served over crushed ice and garnished with full sprigs of mint. Kentucky, I’ve been instructed by my host and bourbon aficionado Jeff Call, takes its bourbon (a subset of the whiskey family) very seriously: Federal mandate dictates that only whiskey made in Kentucky can legally be called bourbon – and only bourbon is served at the Derby. Additionally, bourbon must be produced in Kentucky with water from a Kentucky source and contain 51% corn; it must be fermented using a “sour mash” method; and it must be aged in new, charred oak barrels for a minimum of two years.

We each have a mint julep upon entering the infield; it’s minty, sweet, and quite strong, especially for 11 A.M. Another Derby classic is the Bloody Mary – made with lots of Tabasco and garnished with crunchy celery and olives. The mimosa is also a popular Derby drink, as evidenced by the growing pile of empty champagne bottles at a nearby drink booth.

Folks around us are exceedingly polite and even more exceedingly chatty. Since our arrival, we’ve had strangers chat to us in stores, at the gas station, and while walking down the street. This level of friendliness and familiarity is disconcerting at first, because in my hometown of Chicago, both eye contact and any sort of conversation with strangers are best avoided. But after a while, I relax when I realize people are chatting just to chat, not because they want to distract me and then rob me.

The politeness factor has proved a huge bonus amidst the Derby crowds. Whenever I’m jostled, I get a sincere, “Pardon me, ma’am.” The “ma’am” is also distinctive to the region. Upon being called “ma’am” a number of times my first day in Louisville, I wondered aloud if it was a comment on my age (I think of my mom as “ma’am”) but was quickly told by a Southerner, “It’s the South. My 18-year-old daughter is called ‘ma’am.’”

As we sit on our bench, we chat with a couple who has been coming to the Derby for thirty years. They’re dressed casually but purposefully; the man proudly points out the University of Missouri mascot on his socks. A woman from Texas with a mouthful of gold teeth tells us she’s here for the first time, while Manny the Derby Regular plants himself next to us and doesn’t leave until we do. He and his friends have been attending the Derby for decades, and he regales me with stories and advice: “I just walked into the V.I.P area and flashed them my wristband from last night’s Casino trip. They let me in. If you look like you know what you’re doing, they’ll let you through.”

Manny introduces me to Good Time Charlie, who I am told is a Derby fixture – as is a very large man named Dell, who sports a very large, brown suit with shiny vertical stripes. “There’s Dell!” Manny says. “What a treat!”

As Manny and Dell discuss the horses, I ask Charlie how he got his nickname. “I once owned a bar,” he says, “and held a contest for its name. Ninety-nine percent of people said I should call it ‘Good Time Charlie’s.’” When I ask why, he looks off into the distance: “That bar was a good time.” Charlie confirms that he was, in fact, in prison, and is delighted when he hears I’m from Chicago: “That’s where I was in jail! Yes ma’am – Cook County!” I never quite learn the details of his incarceration, because our chat is constantly interrupted by his friends and fans. Everyone seems to know Good Time Charlie.

By 5 P.M., much of the food has run out. Rumors swirl that the overcast skies misled many of the vendors into underestimating the crowds. As I wait in a food line I am told, with typical Southern courteousness, what that particular booth is lacking: “I’m so sorry, ma’am, but we have run out of fries, pretzels, and cheese for the cheeseburgers.” What’s left are hamburgers, and we enjoy these fresh off the grill and topped with mustard. The ketchup has, of course, run out, and of course, everyone is very sorry for this inconvenience.

At 6 P.M., most of the beverage vendors are out of mint, ice, and glasses. But no one seems to mind as long as there’s still alcohol available. A friend of Manny’s says, “I told her, ‘just pour the bourbon straight into this used glass, honey.’”

The Kentucky Derby race brings an enormous surprise: Mine That Bird, last out of the starting gate, finishes first in a dramatic upset. I stand in a crowd of hundreds and view the race on large screen. I watch Mine That Bird fly over the muddy field and first catch up to the pack of horses and then overtake them. The tiny jockey beams from the screen. I’m thrilled for both him and the gorgeous horse, because who can resist such an underdog fairy tale?

Mint juleps are delicious.

It is apparent, though, that no one around me shares my sentiments or has bet on the winning horse – most folks throw their betting slips on the floor. The horse had estimated odds of 50 to 1, so a $2 bet will net the winner around $100, plus the amount of the original bet. I read later that the horse won by 6 3/4 lengths, the largest margin of victory in the Derby since 1946, and ran the fastest final quarter since 1973. That, to me, shows the very best possibilities of sports events – despite hundreds of predictions, polls, and opinions, a horse that many completely discounted ran to a stunning victory.

Manny and Company invite us to join them at their next destination, the casino – but we beg off, instead meeting our hosts at a neighborhood bar, which quickly fills up with fellow Derby spectators. Women take off their hats, kick off their heels. Men open the top buttons of their dress shirts. We describe the day excitedly and scroll through the hundreds of pictures on my camera. As I describe Good Time Charlie, everyone laughs. “So was it a good time?” I’m asked. It certainly was.

CR