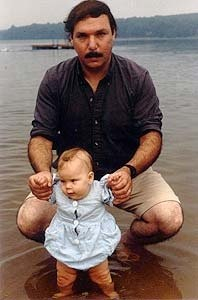

Born in Toledo, Ohio in 1950, Leonard Kress grew up in and around Philadelphia and graduated from Temple University with a degree in Religious Studies. He also has an M.A. in English from the University of Illinois, Chicago, and M.F.A. from Columbia University in New York. His family was originally from Warsaw, Wilno, Kovno, and Minsk, and he spent a year studying Polish literature and folklore at the Jagiellonian University in Krakow, Poland. In addition to poetry, he writes fiction, non-fiction and has translated some of the work of Adam Mickiewicz, Jan Kochanowski, and Szymon Zimorowic.

Born in Toledo, Ohio in 1950, Leonard Kress grew up in and around Philadelphia and graduated from Temple University with a degree in Religious Studies. He also has an M.A. in English from the University of Illinois, Chicago, and M.F.A. from Columbia University in New York. His family was originally from Warsaw, Wilno, Kovno, and Minsk, and he spent a year studying Polish literature and folklore at the Jagiellonian University in Krakow, Poland. In addition to poetry, he writes fiction, non-fiction and has translated some of the work of Adam Mickiewicz, Jan Kochanowski, and Szymon Zimorowic.

He has completed a new verse translation of Pan Tadeusz, which is available at his website (http://leonardkress.com/). He has also published four collections of poetry, most recently, The Orpheus Complex. He currently teaches religion, philosophy, and art history at Owens College in Ohio. He is married to the artist/printmaker, Mania Dajnak, and they have three children.

***

For Ula, on her death

After the Polish of Jan Kochanowski

Hangers draped with clothes you’ll never wear;

they miss the warm touch of your body. Moths

will soon begin to feed upon that cloth;

What rhetoric will persuade me now to clear

your closet out? The iron sleeps beside

the starch, ribbons remain wrinkled and knotted,

under the golden clasp…Flowers on your dress, potted

in the fabric of our grief, bloom since you died.

Useless flowered garments, they should be boxed

and given to the poor. I fear we’ve lost

too much in boxing you instead, this crate

shipped off to Hades, its cargo-my fate.

For I‘ve just sealed this oak chest’s heavy lid,

forever shutting away the dowry and the bride.

(from The Orpheus Complex)

OPRHEUS TAKES ON THE HAGY

Oj ciezki ciezki, ten kamien mlynski…

Bo kamien mlynski woda obroci,

A stan pannienski juz sie nie wroci…

(the millstone is oh so very heavy…

but even water can make it revolve,

but innocence lost can never return.)

Polish folk song

If only to taunt death–we’d leave the pike

at least once each weekend for this path paved

down to Hagy’s Mill, certain we were saved

from skid and oncoming crash. We’d pack

the Dart like a harvest cart of rye and buckwheat

and negotiate the downward spiraling curves,

hawklike in our swoop, and screech and steal and swerve

to the old mill whose stone had not pressed its weight

since the Revolution. Down to the Schuylkill,

the sure-kill we joked, hidden river in Dutch,

meeting others like us, in honking calls so close.

Or if girls were along, open to our blind touch

and entering, then we’d halt, dark and thrumming still,

to let death take part of them and cast off us.

(from The Orpheus Complex)

Polish Oratorio

I was tutoring the son and daughter of the great composer.

Conversational English for her, literature for him;

Together we struggled to bring Howl into Polish,

Served tea & cakes by a poor relative

Who also raked leaves, tended streaming pots, and read

Romances in the corner. No one felt guilt

In this grand manor, by the Byzantine Church with its gilt

Cupolas. Moravian chocolates, Moldavian wine–gifts for the composer

Delivered daily. Baltic herring, Egytian reeds

For his son’s oboe. It was rumored the government feared him

More than the shipyard workers of Gdansk. All’s relative

When it comes to revolution, the authorities polish

Their image by letting him have what few Polish

Citizens have. State of War. Show trials. Guilt.

Foreign investment. Nostalgia. Plum-jobs for relatives-

It all unfolds in front of us, while the composer

Composes in Paris. And who can blame him-

Sycophants, students, impressarios, no time to read

The Warsaw papers. His latest piece, reed-

Heavy and trenchant, its libretto rife with Polish

Romantic tropes. Everyone expects great things from him.

I must be the only one who feels guilt

Around here. The daughter’s composition

Book is full of backwards writing. Alina, her country relative

Burns husks outside and wax effigies from other relatives

For the Day of the Dead celebration. I’ve read

About her gap-toothed smile (mark of Venus-composer

Of love) in medieval astrologies. Soviet mascara, nail polish,

Quick to shed tears, but ardent in desire and guilt-

Free. Everyone, including me, in awe of him,

His early symphonies expounding Eastern Orthodox hymns,

Basso profundo replaced by strings that question relative

Pitch. Taking on the West’s unbridled guilt

Of Hiroshima & Auschwitz. The rampaging Red

Army killing fields and forests, a generation of Polish

Professors, priest, and poets lost. Revived in his compostion.

The Idiot

I was invited to read some of my poems

At the Polish Embassy in DC,

A celebration, of sorts, of Zbigniew Herbert’s

Life and work, a decade after his death,

His year, the Polish Sejm proclaimed

Of course, I wasn’t the only reader

There-and one distinguished guest, who didn’t read,

Though he’d authored a slew of works about the poetics

Of arms control and whose most dubious claim

To fame- lauded only, I think in DC-

was helicopters in Vietnam, the death

And destruction they brought. What would Herbert’s

Mr. Cogito, his everyman say, since Herbert

Often spoke through him? I dreaded having to read,

Like some spokesman for so much death

And suffering, so I chose my poems

Carefully, after wandering all day through DC’s

Museums, wary of sounding any sort of proclamation

Or making any great moral claims

For poetry, though I do partly believe. Unlike Herbert,

I didn’t live through war, revolt, or prison. My trip to DC

Was funded, though I have, of course, done the reading.

My long trek made me thirsty, late, and poetry

Was not on my mind. To keep from dying,

I’d just taken my heart meds, and in the dead

Silence of beginnings I reached out to claim

A glass of juice, gulped it down, grabbed my poems,

Formulated some rationale how they related to Herbert,

then recalled with horror what I’d read

On the pills-Avoid grapefruit Juice. Here in DC

It was bound to happen, a foreign embassy in DC,

Convulsions, drool, seizures, trashed decor, I’d die

Spotlighted, pathetic, the kind of scene you’d read

in Dostoyevski’s Idiot. As if a proclamation

had been issued, this might be the year of Herbert,

but don’t expect the century to care about his poetry.

the pope’s visit

brings to mind an earlier

visit by an earlier pope

still Archbishop

of Krakow

at a shrine in Bucks County, PA

–the Black Madonna–

face charred by retreating

Swedish legions

who picked up a few polkas

to bring home on the way

“You know of course that the word Polka can

also mean Polish Woman”

“Oh”

Mania was there, summer job

helping some hired guy keep the books

The cooked books

Anything to keep out of the kitchen

kapusta, nalesnkiki, ziemiaki

out of the way of the hungry monks

and the Pope not the new one, not yet

Pope now all but canonized

–intercessory–

asking her

which way to the bathroom?

Poppy Seeds

Zosia

After stopping at the bakery

I stepped inside the tiny Russian Church

behind the slaughterhouse and pressed my lips

against the icon glass, and though the priest

began to swing his censer back and forth,

faster, higher, as though the smoking golden

globe was his blond daughter on a playground

swing–whose white communion dress now whooshed

above her face, breathless from the mighty push,

my knees went weak and bent to find the floor

just as the hidden choir voices met

to sing the Mass’s final word–Spassiba!

and when a sweeter voice, younger than

the rest, pierced the iron chord and fluttered

mightily above before it vanished

into the risen Christ captured by

the ceiling vault, my forehead grazed the tiles,

my lips the ground–just like the grieving Russian

women across the San who welcomed roaming

beggars in case their painful stare bestowed

the riches of a saint. I tasted salt,

not from the crying icon, but from the heavy boots

that tracked it from the sidewalk slush

after the Elder scattered it like feed.

My hand had crushed the spiral cake, ripped through

the paper bag, and from a tiny perfect

slit, just like the belly of a frog

a curlew’s beak has torn beside a pond,

countless seeds, sweet and dark, now burst.

(First appeard in Missouri Review and then in Sappho’s Apples)

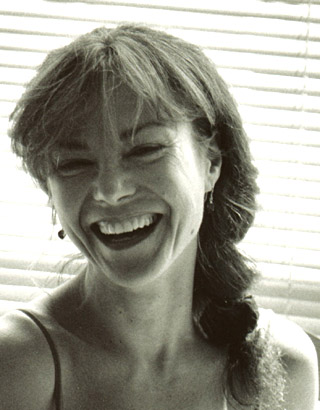

Cecilia Woloch was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and grew up there and in rural Kentucky, one of seven children of a homemaker and an airplane mechanic. She is the author of five award-winning collections of poems, most recently Carpathia, published by BOA Editions in 2009. She is currently a lecturer in the creative writing program at the University of Southern California, as well as the founding director of The Paris Poetry Workshop. She spends a part of each year traveling, and in recent years has divided her time between Los Angeles, California; Atlanta, Georgia; Shepherdsville, Kentucky; Paris, France; and a small village in the Carpathian Mountains of southeastern Poland. Her website is http://ceciliawoloch.com/

Cecilia Woloch was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and grew up there and in rural Kentucky, one of seven children of a homemaker and an airplane mechanic. She is the author of five award-winning collections of poems, most recently Carpathia, published by BOA Editions in 2009. She is currently a lecturer in the creative writing program at the University of Southern California, as well as the founding director of The Paris Poetry Workshop. She spends a part of each year traveling, and in recent years has divided her time between Los Angeles, California; Atlanta, Georgia; Shepherdsville, Kentucky; Paris, France; and a small village in the Carpathian Mountains of southeastern Poland. Her website is http://ceciliawoloch.com/

Bozena Zaremba’s article about Ms. Woloch and Carpathia, her recent book of poems, appeared previously in CR.

***

Postcard to Myself from the Lower Carpathians, Spring

I slept in a room filled with white moths. In a wooden house in the lower Carpathians – Beskid Niski – each silvery night. I made my bed in the room’s far corner, white moths settling like quiet petals on every surface as evening fell. They folded their wings and clung to the walls without a quiver as I undressed. I knew, as soon as I switched off the lamp, that the air would go pale with their fluttering. I knew, in my sleep, one might light on my arm, on my cheek, in my hair, without waking me. In this room, also, the seeds of wildflowers gleaned from the meadows were spread out to dry. What I learned about gentleness then. What I learned to be gently less wary of. I want not to forget those nights in the lower Carpathians, deep spring, sleeping alone: the white moths swirling as I dreamt; the meadows baring themselves to the moon.

Carpathia

Having rinsed off the soot and stink

of the Polish train,

having sung with the child.

Having eaten and laughed and wept,

had my vodka with apple juice,

my bread.

Having walked through the fields

at dusk, and into the forest

and back again –

meadows of buttercups,

thistles with bristling heads,

the first blue cornflowers of June.

Having opened my arms to the sky

falling back on itself

in my dizziness.

Having taken the small purple berries

that dropped from the wild bush

into my palm

-Siberian berries, like tiny plums –

put their sweet bitter inkiness

onto my tongue.

Having failed and failed at love.

Having gone anyway,

breath after breath.

Having trusted the world to be kind

and stood in the doorway

and listened for wolves

and heard my own dead in the high

grass whispering,

beloved, beloved, beloved.

Postcard to X from Warsaw, Ulica Piekna (“Pretty Street”)

The old woman selling flowers next to the archway at ulica Piekna was wearing orange lipstick today. Shiny orange lipstick, and a smile; her black kerchief knotted under her chin. She was smoking a cigarette, all her tulips arranged in plastic tubs at her feet – gaudily purple and yellow and red. I could tell she felt quite the coquette, and it made her mouth look lovely, in fact. That slick of peach on her lips as she sat with her back to the flat gray wall. The building behind her a relic, too. My friend says the communists built these apartments to show the workers how they might live. Though only the highest officials – most brutal, most damned – were given such balconies, of course. Everyone else in the dreary blocks built on the ash of the murdered, the crushed, stinking forever of cabbage and piss. But today there was rain, here in Warsaw, then sun. The wind had shifted, then shifted again. The clouds moved like swans across the sky. And the old woman – I passed her twice – made a few zlotys on flowers, I’d guess. She sat there for hours on Pretty Street, her mouth like a pearl in her wrinkled face. And you – you know who you are; you tried to be human once but you failed – could not have touched this woman. Ever. She, with her tulips. Not bitter. Nor I.

Dzien Dobry

“Exile is an uncomfortable situation. It is also a magical situation.”

– Helene Cixous

In Rzepnik – a village

of maybe twenty families

strewn across hillsides, fields

on the banks of the river

named Merk, as in Dark,

in the lower Carpathians (end

of the world): each house

with its weary cow, its chickens

scratching the dirt in the yard;

each window its white

lace curtains; each morning

its light – in the glorified

shed my friends call

home (bare floors

swept with a broom made

of twigs; bathwater heated

at night on the stove) –

where I woke late

one spring day, having dreamt

through the clamour of church bell

and bird-cry, alone,

into absence and hush

(where had everyone gone?) –

the front door ajar and the fire

unstirred; the faint hum of flies

buzzing over the wreckage

of breakfast – half-eaten

apple, brown bread, tin of fish –

where I had grown thin

on a diet of grief, unspeakable

consonants caught

in my throat; no word

from my love in that far

other world, nothing

in weeks that did not

taste of ash – and, sighing

put on the kettle to boil

(rat in the well last year)

rinsed out my cup, then,

sensing someone behind me, turned

to whomever had entered

(no murmur, no knock)

and waited in silence:

the neighbor, Kasczyk –

a man I’d watched bent

at his work in the fields

and thought: I know nothing,

some book in my lap – strange

to these villagers, strange

to myself – lost,

with no language

to speak to him now

as he stood in that shimmer

of sunlight and dust, boots

caked with mud, body

worn as a blade

– almost transparent –

fresh eggs in his hands:

the shells tinged

with blue and still warm,

I could tell, by the way

he was holding them, cupped

in his palms, the moment

I felt him there – (shift

in the air) in my stubbornness,

bitterness, terror of filth –

and facing him, wordlessly,

nodded my head.

Dobry, he said,

at last: good, and was gone –

only sun on the table

his gift of fresh eggs.

Dzien I called out

to the bright, empty room –

having meant to say

thank you, dziekuje,

and said only dzien, only

day, for dzien dobry,

good day – when I woke

to the grace of eat that

which is offered, knew,

in that light, where to turn.

Cabbage

My mother’s hands are quick.

She stuffs the cabbage leaves with meat and rice,

rolls them into fists.

The pressure cooker screams, its jet of white steam

wets the kitchen.

Work to eat.

My father bowing hungrily,

my brothers growing into men,

My sisters making dainty piles of soggy leaves,

like skin.

At every meal, we eat our mother’s hands.

At every meal we thank the gods of cabbage

who are green.