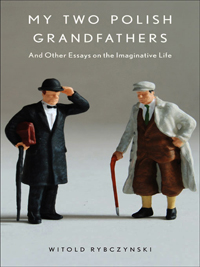

My Two Polish Grandfathers And Other Essays on the Imaginative Life

My Two Polish Grandfathers And Other Essays on the Imaginative Life

By Witold Rybczynski

Scribner 2009

“I should have been a true Pole rather than a make-believe Scot,” writes Witold Rybczynski in his latest book, the beautifully written My Two Polish Grandfathers. Born in exile in Scotland, where his parents happened to be stationed with the Polish army during part of WWII, Rybczynski became an immigrant several times over during his life, spending part of his childhood in London, then moving with his parents to Canada when he was ten and finally choosing to settle in the United States in mid-life. Everywhere he went, he carried with him his family’s story and now he’s finally put it down on paper, creating a fascinating read.

Throughout his book, Rybczynski touches upon the issue of identity, albeit in his trademark understated manner. As was common for boys of his era, Rybczynski was fascinated by war and spent a good part of his Quebec boyhood building forts and playing war with his neighbourhood friends. He also loved war movies and saw many of them, though their plots never had anything to do with the stories he had heard from his parents. “Nobody made films about […] Poles training in Scotland,” he writes. Nobody made films, and not many British or North Americans knew about, Polish parachute brigades, Polish pilots in the Royal Air Force, the Warsaw Uprising, Yalta. The stories he grew up hearing were not validated in the wider world, making them seem even more remote and fairy tale-like.

Rybczynski, a renowned architect and professor of urbanism at the University of Pennsylvania, Wharton, is a seasoned writer, currently a columnist for Slate.com and an author of over two hundred books and articles on subjects related to architecture and design. A recipient of numerous prizes, he’s written for publications such as the New York Times and his books have ranged from the history of the screw (One Good Turn) and exploration of the act of designing and building a house (The Most Beautiful House in the World) to the biography of landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, creator of New York’s Central Park and Montreal’s Mount Royal Park (A Clearing in the Distance). Rybczynski has been credited with bringing architecture and design to lay readers and now he brings his experience as a child of Polish exiles to a mass English-speaking audience.

Rybczynski acknowledges that the events that had the most impact on his life happened before he was even born. The outbreak of WWII changed his family’s fortunes and way of life forever. And life for his family in pre-war Poland was good.

Rybczynski’s maternal grandfather, Mieczyslaw Jan Hofman, was a self-made man who worked his way up to become the president of Bank Handlowy (Commerce Bank), the largest privately-owned bank in pre-war Poland. The Hofman family lived in cosmopolitan Warsaw in the vicinity of the Lazienki Park, near Warsaw’s Champs-Elysées, in Rybczynski’s words, the Aleje Ujazdowskie. Their neoclassical castle-like villa was originally designed by an Italian architect for a leading Polish writer and was big enough to house the family of six along with a household staff of nannies, servants and watchmen plus spare room for rented offices, a library, a wine cellar and other facilities. There were hunting outings and elegant balls to attend. Summers were spent in a house just outside of Warsaw, where the children could roam free and play sports. In short, a charmed upper class life and a happy family to boot.

Rybczynski’s paternal grandfather, Witold Erasmus Rybczynski, led an equally charmed, if quite different, existence. A physicist, researcher and university professor in a bustling cultural metropolis of Lwów (now Lviv), he was set to pursue a promising scientific career when, close to mid-life, he fell in love and moved to the small town of Tarnów to be close to his life companion. He traded a busy research life with postings to universities in Austria and Germany for a career as a high school teacher and, after retirement, a writer. He led a quiet, contented life with his companion in her country estate, where his friends included one of Poland’s leading painters, Jacek Malczewski.

Rybczynski admits that, growing up, even though he knew his family’s stories well, he had a hard time relating to them. Having to share a room with his brother in his family’s bungalow just outside of Montreal, where the family moved when he was ten, castle-like villas, hunting parties and country estates seemed to him a world away. The family couldn’t visit communist Poland and, at any rate, all of their properties were destroyed when Warsaw was razed after the Warsaw Uprising. He never met his grandfathers; pre-war life was gone for good. While he heard the well-worn phrase “przed wojna” often during his childhood, to him it represented but a fairy tale.

Rybczynski continues My Two Polish Grandfathers with stories about growing up, first as a young boy, then a student and budding architect in cosmopolitan Montreal. Having dropped the British accent of his early childhood, he easily slipped into the life of an English Quebecer, a lover of jazz and girls, a top student, an adventurer, an architect, a world traveler. He dabbled in children’s theatre and worked with the renowned architect Moshe Safdie, before finally pursuing a career in urbanism and minimum cost housing as well as writing about architecture. An interesting life, made more interesting by the fact that it’s consciously explored and examined.

In another episode, Rybczynski writes how, during his travels through Europe after he graduated from university, he found that the French, unlike Canadians and Americans, had no trouble pronouncing his “two unpronounceable names.” Moreover, despite being born and raised outside of Poland, he was quickly considered by his French friends a polonais, not a canadien. “It was a novel feeling,” he writes, for in Canada, despite eating bigos and barszcz at home and celebrating name days instead of birthdays, he was a Canadian and an English Quebecer, albeit a trilingual one.

If there is one criticism that I have of this book, it is that Rybczynski does not explore further the issue of identity in general, and how his particular identity has shaped and influenced his life, both public and private. While the author touches upon the conflict children of immigrants often experience with their parents, the parents’ youth being so different from their children’s that it is hard for them to find common reference points, there is nonetheless a lot more room to consider the issue. As an ambitious student, an accomplished architect and a prolific writer, there must have been a lot more times when the author’s identity came to the fore.

Perhaps, though, in his subtle ways, Rybczynski already addresses this point. “Home is always a refuge from the outside world, but never more so than for the child of foreigners,” he writes. Is this why he’s written so much about the idea of a home and why he’s made housing his professional career?

Written with a masterful attention to detail and numerous anecdotes that bring the stories to life, My Two Polish Grandfathers is a fascinating read from a fascinating writer.

CR