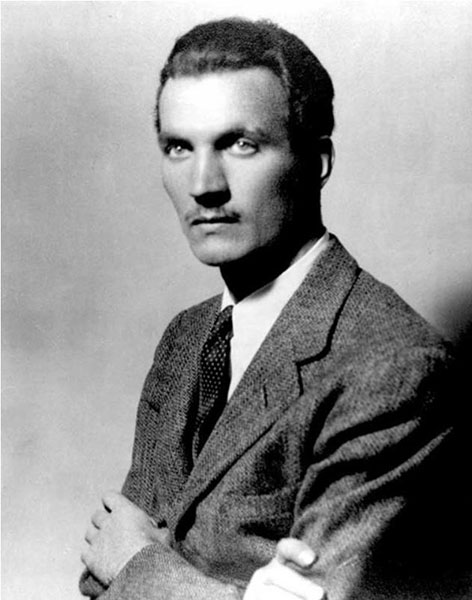

Just a glance at this photograph tells you that there’s a story behind it. Dramatic black and white photography, excellent composition. The young man, wearing a soldier’s uniform and beret, is imposing. Not just because of the erect posture, his head up, eyes looking into the distance but, if his expression reveals anything, it’s stoicism.

Just a glance at this photograph tells you that there’s a story behind it. Dramatic black and white photography, excellent composition. The young man, wearing a soldier’s uniform and beret, is imposing. Not just because of the erect posture, his head up, eyes looking into the distance but, if his expression reveals anything, it’s stoicism.

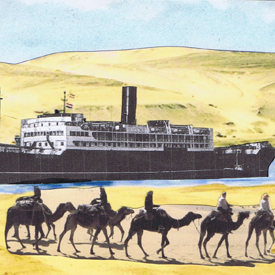

The year is 1946, the young man is Bolesław William Makowski, age 21. At that age he is already a survivor of the Soviet Gulag, and a veteran of the Polish army who fought at Monte Cassino. He is on board the ship, Sea Snipe, just leaving England for Canada. He has with him a contract from the Canadian Ministry of Labour committing him to work on a farm.

The ship arrives in Halifax on November 23, 1946. The soldier probably passed through Pier 21, the fable entry point for immigrants that is now a museum. Odd accents and strange sounding names are more acceptable now.

The second photograph is just as riveting. The same young man, this time in a suit and hat, standing alone on a country road. The scene is barren, isolated. Is he hitchhiking? His face is partly in shadow but you can see the same stoical expression.

The second photograph is just as riveting. The same young man, this time in a suit and hat, standing alone on a country road. The scene is barren, isolated. Is he hitchhiking? His face is partly in shadow but you can see the same stoical expression.

The story is every bit as dramatic as the photographs, especially since it was so long untold. Makowski came to Canada as part of the Polish Resettlement Corps, an agreement Britain worked out with Canada’s Ministry of Labour allowing Polish veterans into Canada with a contract committing them to two years of obligatory work on farms or in mines or forests.

Not the homecoming that victorious allied should have had but the most cynical condition in the agreement was that these men were instructed not to discuss their wartime experiences with Russia. By this time Russia and the West were well on the way to the Cold War but it was important to maintain the fiction that until now, the USSR had always been a faithful friend, had never been Hitler’s collaborator, and that Poland had not been betrayed. According to the best practice of public communication, if you want a story to go away, say nothing. The silence lasted a long time.

Within this framework were lived the individual stories. Young Makowski, stoical but not cynical, remained determined, hopeful, and ever observant of human nature, the last aided by a sense of humour. His first glimpse of the deserted streets of Halifax, devoid of any sign of human interaction, made him wonder if the population had been evacuated. He would later learn that Canadian cities, mostly dominated by Protestants, provided little in the way of pleasure, at least on public display. A brief glance at ethnically mixed Montreal, where he changed trains, offered a glimmer of hope for the future.

His destination was Kitchener, Ontario where the Polish veterans were met by a group of farmers who had come to appraise them in a manner all too similar to a slave market. This indignity was compounded by the realization of a bitter irony: these Polish veterans were admitted to Canada to replace German POWs… who had gone home.

Until the First World War Kitchener was called Berlin, the change of name necessitated by the anti-German feeling aroused by that war. But Germans remained a numerous ethnic group in the region and Makowski’s first employer was, indeed, a German who liked his Polish veteran a lot less than he did his German POW, all the more because he resented having to pay this Polish farmhand.

Within a couple of months the two parted company, and Makowski was assigned to another farm. His experiences, like that of most of these “indentured” labourers, were far from positive. In many cases the farmers tried not to pay their Polish workers, or they cheated them in some way. The living quarters were often barns or at best unheated, unventilated attics, their food rations inadequate, the working hours exploitative, and their employers frequently inflicted verbal, and at times physical, abuse.

In time, the Poles working in the area manage to communicate and Makowski organized a meeting to discuss how they could improve their working conditions. This lifted their spirits but accomplished little else.

Soon after, Makowski was hit once again by his employer, a man much bigger than he. He fought back. Small and undernourished, he was a trained fighter and ultimately gave back more than he got. And was promptly arrested. The trial, pitting an outsider against a local farmer, attracted a large and noisy crowd. The verdict was guilty, but the sentence, to everyone’s surprise, was suspended. The judge, a veteran, remembered the Poles from Monte Cassino, and did not share the local animosity towards them.

Branded a troublemaker, Makowski had no chance of finding other work in the area. In any case, he found the tedium of the farms, the coarseness, ignorance and brutality of the farmers, the exploitation and the prejudice debilitating. The judge suggested he go to the mining area of Kirkland Lake, a prospect that sounded vaguely like being sent to the Gulag again. He headed for Toronto instead but one look at that city as it was in the 1950s persuaded him that perhaps Kirkland Lake might not be too bad.

Makowski’s observations in the north are fascinating. For a start, he loved the “cosmopolitanism” of Kirkland Lake compared to Ontario. There were people there of many different ethnicities and no dominant group with a sense of entitlement. He sympathized with the native population whose lands were constantly expropriated and exploited by private companies with no regard for either the native people’s claims and rights, or the ecological crime of clear-cutting vast tracts of forest after which they simply moved on, taking the profits with them.

Makowski chose not to work in the mines but found work on farms owned by Poles and Ukrainians. It was hard work and poorly paid but the people were pleasant. As the months passed and his two-year commitment was coming to an end, Makowski gave more thought to the career he had planned back in Poland, before the war. He always wanted to be a teacher.

Although his education had been cut short by the war, he had earned his high school diploma while still in the army and spoke very good English. He headed back to Toronto, almost penniless. Wandering around the city looking for work he spotted a “Dishwasher Wanted” sign in a very modest Greek restaurant. He was hired on the spot but first, said the owner, a heavy set middle-aged woman, “Sit down and eat.”

His faith in humanity restored, he worked hard, saved his money, and applied at the University of Toronto. The response was disheartening: what significance can your academic standing have from your so-called “lyceum?”

He moved to Montreal, in his opinion the only city he’d seen so far worthy of the name. He quickly realized he would fare no better with McGill than with the University of Toronto so he applied at the Universite de Montreal. This French university didn’t have a problem with the word, “lyceum,” treated him with respect and encouraged him, though he would have to learn French to study there. Makowski, who already spoke three languages, happily added one more.

He worked, he studied, and he succeeded. His life fell into place. He became a teacher, a job he loved, and married a girl he had met during the war. Eventually they moved to Ontario after all, though by then, with the arrival of a so many immigrants, the place was more civilized.

He worked, he studied, and he succeeded. His life fell into place. He became a teacher, a job he loved, and married a girl he had met during the war. Eventually they moved to Ontario after all, though by then, with the arrival of a so many immigrants, the place was more civilized.

Makowski wrote about his experiences in a book, Powojenne Wiatry, published in 2008. He died in 2012, before he had time to translate it. It’s an excellent book, with a marvelous cast of characters and rich with humour. He writes about a different and more primitive kind of Canada, and a difficult episode in the life of the Polish diaspora, a story that took too long to tell.

CR

My dad arrived on the SS Sea Snipe with Makowski in 1946 at Pier 21 in Halifax…the Sea Snipe left Naples, Italy for Canada…..not England. Did you have info otherwise on this?

hania

My mistake. Thank you for the correction.

My Father also arrived on the Sea Snipe and was allocated to Ontario. Does anyone have information on the Polish army corp#2, that they came from.

Further information on the Polish Second Corps can be found at your local SPK (Polish Veterans Group). If you are in the Toronto area, you should visit SPK Branch 29 at 206 Beverley St. They have a museum on the Polish Forces, and the curators are very knowledgeable. I also invite you to contact me at polishexiles@gmail.com for more information.

Krystyna Szypowska

Would be great to see his book translated in English. I do not have a website but I do have a Facebook page.

Allan, I agree, an English version would be terrific, as I cannot read Polish.

Did you also have relatives on the ship, S.S. Sea Snipe, which arrived in Halifax, November 24, 1946.? My Father was on this ship, and then destined to Ontario, Long Branch.

I trying to find details regarding the Sea Snipe, leaving Italy, ie. Date of departure, which port(Naples, or maybe Ancona), Passenger list, etc.

Thanks for the message John. My father was on the Sea Snipe and arrived in Halifax on the same date.

Sorry for taking so long to reply John. I lost track of this website.

Today, November 24, is the 74th anniversary, of the SS Sea Snipe arriving in Halifax Pier 21. My father, Michael arrived on that ship, from Naples, Italy 1946. Does anyone have any further information on this voyage? John Taras