It’s easy to say which nation has the fastest trains (France) or the largest number of prime ministers who’ve probably been eaten by sharks (Australia), but it’s impossible to know which country has the best writers, let alone the best poets. Even so, if cash money were on the line, you’d find few critics willing to bet against Poland.

It’s easy to say which nation has the fastest trains (France) or the largest number of prime ministers who’ve probably been eaten by sharks (Australia), but it’s impossible to know which country has the best writers, let alone the best poets. Even so, if cash money were on the line, you’d find few critics willing to bet against Poland.

– David Orr; The New York Times; July 29, 2007

Isabelle Sokolnicka concurs, and thinks the language may have something to do with it.

A very short night sleep, another tough wake-up… only to be sitting in a windowless class to hear the monotone voice of a teacher explaining the symbolism behind Prus’s “Lalka.” Torture, you say?

Well, torture can be good sometimes. No, I’m not into masochism, God forbid. And I’m not insane, yet. I’m just always pleased to remind myself that those dreadful Saturday mornings of Polish school, 13 years of them, which I was convinced were an absolute waste of time and of my oh-so-very-precious energy, are actually directly responsible for my being able to still speak my mother-tongue. Yes I speak Polish. Very good Polish. And no, I wasn’t born there. And you know what? Worse even, I spoke French at home, because both my mother and grandmother were raised in France.

I know, don’t say anything. I’m starting to get used to that I-don’t-know-how-she-does-it look of surprise and admiration. (Ignore the ego bubble.) And fortunately, I’m not the only Canadian who can claim to be and feel Polish, not only because such is the blood that runs through my veins, or because I eat barszcz for dinner, but because I know about my country’s culture and history, and I understand the sound of its music, movies and poetry.

I speak Polish and I’m very proud of it. So the moment my ears hear the question: ‘What’s the use?’ my immediate reaction is angry indignation.

I’ll tell you what the use is. Have you ever tried reading Polish? Or attempted to analyze its structure? The language is damn complicated. To be exact, it’s one of the hardest in the world. The hardest, you say? Absolutely.

Actually, some studies have shown that a child becomes fluent in English on average at age 12, for Polish, the age is 16. You’ve gotta be kidding me! No, I’m not. And it’s not due to some superior phonetic aptitude of American kids, it’s simply that Polish in its grammar, syntax, conjugation and vocabulary is so very sophisticated that it takes quite a bit of time to grasp.

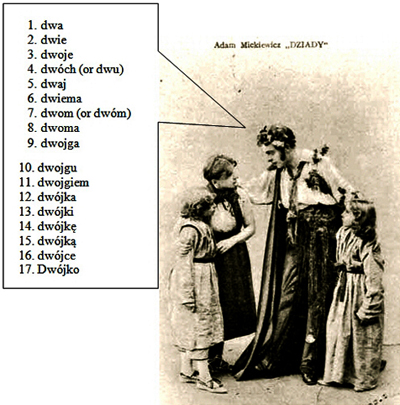

With 7 cases, 7 genders, 17 (yes, 17) different forms of the number 2, with 95% of its verbs having both imperfect and perfect forms, not even mentioning its tongue-twisting pronunciation or jaw-dropping spelling, Polish has more exceptions than it has rules. No wonder then that it falls within the category of EXTREMELY HARD languages to learn, along with Arabic and Chinese, often ranked harder than Russian, Finish and Japanese.

But then, the good thing is that once you know how to read and write Polish, learning anything else becomes a tiny piece of cake (or I like to believe so). And the seven languages you then acquire and proudly highlight on the first page of your CV just make you stand out a little bit more…

You can still argue that speaking it is really only useful if you happen to live in the little heart-shaped country of 40 million inhabitants. Maybe… although I would tend to doubt it, considering that you can potentially mingle with the Polish Diaspora in more than 90 countries throughout the world. When you know the language, Poland just seems to be everywhere.

And, while useful when traveling, Polish comes in handy for relationships too. It appears to me that there is a real trend in young people to suddenly crave to learn this Eastern European idiom when they find out that their significant other speaks it. They say it facilitates communication and comprehension. Go figure.

All jokes aside: Parents, send your kids to Polish school. Don’t let them watch cartoons or sleep in on Saturday mornings. Seriously. Or find some other effective way to teach them your language. Be creative, be tough, but don’t let them forge their identity without discovering this important part of being Polish.

You’re still unconvinced? What about…:

The fact that there is something strangely beautiful in the unpronouncability of Polish names or the interminable chains of consonants; something unique about a Slavic tongue born in the heart of Europe, and influenced by languages as different as French, Hungarian, German, Italian or Turkish.

And that there is something indescribable and unqualifiable about the subtlety of Polish poetry. The delicacy and depth of the vocabulary, its capacity to represent movement and perspective like no other language, and the very wide range of prefixes and suffixes that can completely alter the meaning of any word are all elements that permit nuanced expressions of specific emotions or particular settings, and on top of that all – with very few words: the perfect ingredients for poetry-making. Read Baczyński, Słowacki, Miłosz and of course Mickiewicz: maybe it’s the authors’ talent but maybe it is also the language that makes it so incredibly natural to step into a true kingdom of literary creativity. Make your kids learn Polish. Make your kids learn Poland. Make them spell solidarność, ojczyzna, or better even – milość. Who knows, this might just be the beginning of a long-lasting love affair with the Polish language… or at least of a friendship with unquestionable benefits.

Coooooooool!!

You could add Norwid, Tuwim … and just think of it .. at list a half of top names in Polish literature and poetry were writing on emigration. Might be one needs to get out to see the beauty of this complexity 🙂 .

No doubt!! Poems of Tuwim to drills in conjugation and declination. Not a coincidence.

Cheers

Coooooooool!!

You could add Norwid, Tuwim … and just think of it .. at least a half of top names in Polish literature and poetry were writing on emigration. Might be one needs to get out to see the beauty of this complexity 🙂 .

No doubt!! Poems of Tuwim to drills in conjugation and declination. Not a coincidence.

Cheers