The Maharaja Jam Saheb Digvijay Sinhi

Between August 1942 and November 1946, close to 1,000 Polish children and their guardians lived in an idyllic settlement on the Kathiawar Peninsula in India not far from the summer residence of the Maharaja Jam Saheb Digvijay Sinhi. They had come at the Maharaja’s invitation from orphanages in Ashkhabad, the capital of Turkmenistan, and Samarkand, Tamerlane’s ancient capital on the Silk Road, traveling in canvas-covered trucks over serpentine roads through the mountains of the Hindu Kush to the sacred city of Meshed, then on through Persia to Mumbai where they boarded a train that would take them to Delhi to be greeted by the Viceroy of India before settling in the Polish Children’s Camp of Balachadi.

Their odyssey had begun earlier on, in 1940, when they were deported from their homes in Poland and sent to the northern or far eastern areas of the Soviet empire by the Red Army that invaded and occupied their country. In 1941, when Nazi Germany turned on its former ally, Stalin’s armies disintegrated within days. Desperate for help, he turned to the Western Allies but, to join that alliance, he had no choice but to release his Polish prisoners, among them thousands of orphaned children.

During the brief period that Poland and the USSR had diplomatic relations, Polish officials set to work to rescue as many of these child prisoners as possible, gathering them from various camps, collective farms and orphanages, or finding them abandoned and fending for themselves after their parents had died. It was imperative to get them out of the Soviet Union but in a world at war, how were they to get out, and where were they to go?

The Maharaja attending a school play

It was then that the Polish government-in-Exile received an unexpected offer of help from the Maharaja Jam Saheb (top). He was at the time the Chairman of the Council of Indian Rajas and a member of the British War Cabinet. As soon as he made his announcement, offers of support poured in: a donation of 50,000 rupees from the Viceroy of India was followed immediately by donations from international and religious organizations as well as from wealthy individuals.

The Soviets had agreed in principle to let the children go but in reality they were not at all keen to have the western world see the condition of the starving children. Nevertheless, the Maharaja’s offer launched a chain of action that could not be stopped. A huge convoy of trucks was assembled, Indian drivers accompanied by local guides and some Polish army mechanics were recruited. Arrangements were made for provision of food and overnight stops along the way, and the first 500 children set off on this incredibly journey.

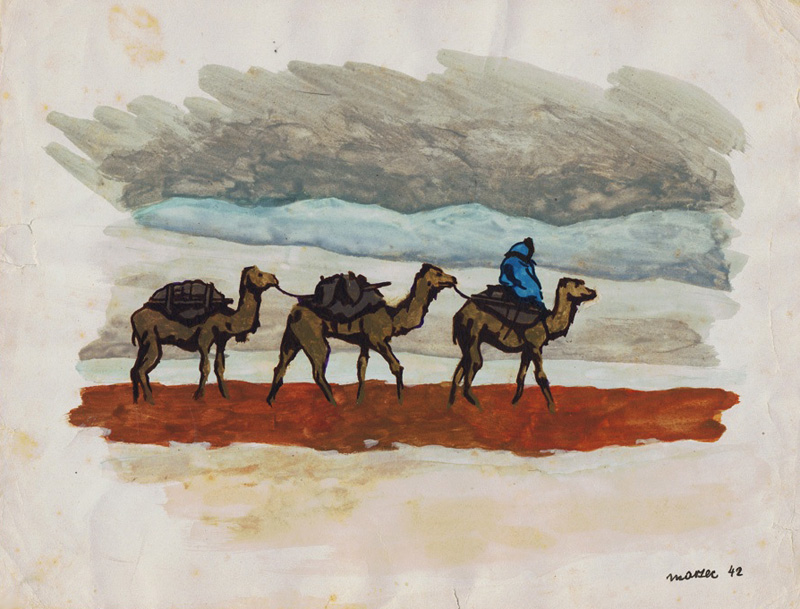

Memoirists record the terror of driving on narrow winding roads hugging the mountain on one side and exposed to a steep drop on the other. There were one or two tragic accidents when trucks drove off the road. Once the mountains were behind them they crossed a desert and experienced the horrors of a sandstorm. Both in mountain and desert there were concerns about attacks by bandits but although they encountered what looked like raiding parties, the horsemen quickly rode away when they saw the children.

In India, the children boarded trains for Delhi where they were met by visiting dignitaries, primarily the wives of colonial officials. In part this seemed to be a kind of public relations tour for the benefit of their benefactors but it also gave more time to get the children’s camp ready. A few donors wanted to have some children turned over to their care but the Polish authorities persuaded them that it was easier on the children to be kept together. Instead, it was agreed that children would write letters and send photographs to their “adoptive parents,” perhaps setting a model for the international adoption plans we have today.

One particularly odd offer of help came in a letter from the Women’s Auxiliary Committee of the British Labour Party offering to “adopt” six orphans and provide them with clothing, school supplies and various other necessities. However, the letter went on to say, “We are anxious that… any little help that we may give should benefit children whose parents were Socialists so we would be most grateful for your cooperation in the matter.” There is no record of interviews with children about their parents’ political persuasions so it seems common sense prevailed.

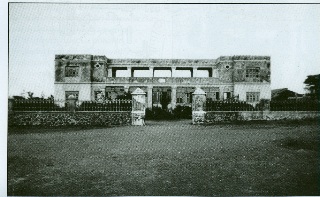

The Balachadi School

Finally the day came when they arrived at Balachadi, a home they could call their own. In the space of a couple of months, a camp was built under the supervision of the Maharaja with dormitories each housing 20-30 children, all of them provided with a wooden bed, a desk, a shelf and a little trunk at the foot of the bed. Each dorm had a couple of communal tables; bathroom facilities were shared. The guardians’ residences had private rooms and shared bathroom facilities. There was a school (left), a chapel, a community centre, an administration office, a dining room, a hospital, doctor’s residence and nurses’ quarters, a town square, a playing field, a laundry, and housing for native workers. Upon arrival, they received their provisions: shorts, white trousers, shirts, handkerchiefs, soap, towels, toothbrush, sandals, and a very exotic looking pith helmet. The looked splendid indeed.

The camp was not far from the Maharaja’s residence so one of his smaller palaces, a lovely, graceful building, served as a school. Also, the camp was not far from the ocean because, as the Maharaja noted, children love to play on a beach and the sea air will help them recover.

This is just one story of Poles in India. There were several other camps, some of them transit camps, and one very large family camp, called Valivade, in which another Maharaja played a large role. All of them are extraordinary stories of courage, endurance, resilience, compassion and, to a large extent, the best of human nature.

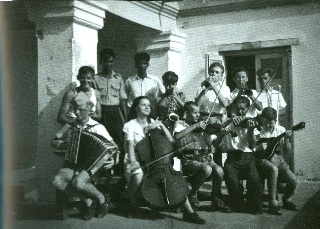

Members of the School Orchestra

But for now, to end the story of the Maharaja Jam Saheb Digvijay Sinhi, we turn to his own words

“I was deeply moved and concerned about the fate of the Polish nation, especially those who were living through this most terrible of wars as children and young people, so I wanted to somehow do something to ease their lot. So I extended an invitation for some of them to come to a country far from the horrors of war. Maybe there, nestled in mountains situated on the shore of the ocean the children could return to good health, could forget the terror they lived through and build up strength to take up their future work as citizens of a free country. I was extremely fortunate that I was in a position to help these Polish children. I care deeply about the Polish nation that is fighting so gallantly against enslavement, a nation that produced such special children. My father was always interested in Polish affairs, which he knew much about thanks to his friendship with that great Pole, Paderewski. They used to meet in Geneva at the League of Nations. I remember one of those meetings. My father took me as a young man to Geneva and there introduced me to his friend, the great artist and statesman. Paderewski noted my hands and said my fingers seemed to be just right for playing the piano, to which my father answered that my fingers may be fine but my ears are not worth a penny. So it was this friendship of my father’s that instilled in me an interest in Poland. Today, when your country is suffering so much, when your people are fighting so heroically and the Polish forces are fighting on every front, when more than a million Poles are scattered across the earth, I am trying to do what I can to save some of the children who must, after their terrible ordeal, regain their strength and their spirit so that they will be able to, in future, fulfill their obligations to their liberated country.”

During those four years, the Maharaja visited the Polish Children’s Camp on many occasions, attending their theatrical performances, their national holidays and other occasions. In December 1945, he attended a special event for the blessing of the Scout’s Standard when he spoke the following words:

“It is a great honour for me and my wife to be the godparents of your standard. May these silver nails which we are hammering into the wooden staff of the flag become the nails in the coffin of the enemies of freedom and of your homeland… I will remain forever loyal and true to Poland, I will always be sympathetic towards the future of your homeland. I feel certain that Poland will be free, that you will return to your happy homes, to a land free from oppression. The Polish spirit, known to the whole world, will overcome its present situation, no matter how long it takes. Defend this flag even with your lives because with this spirit you will overcome everything. Today will remain in the history of Jamnagar as one of the most beautiful occasions. May God bless you and let you return to a free and happy homeland.”

CR

The primary sources for the story of Balachadi are the collective memoir, Polacy w Indiach, 1942-1948, and the archives of the Sikorski Museum in London.

Pingback: Masindi: a Polish Home in Africa

Pingback: February 1940: Exile, Odyssey, Redemption

Dear Irene, My mother,aunts and grandmother were in Africa after the war, and came to Australia. And, over the years my mother lost contact with her best friend – with the Laws here i cannot locate her. They came on the General Langfitt and are all in the register too. After so many years my mother is still wishing to find her friend. I was just wondering whether you could give me any clues as to how i could look for her. This would be most appreciated.Kindest regards.

Pingback: Second Homeland: Polish Refugees in India