Vera Gran: The Accused

Vera Gran: The Accused

By Agata Tuszynska

Translated from the French of Isabelle Jannes-Kalinowski by Charles Ruas

Alfred A. Knopf (New York: 2013)

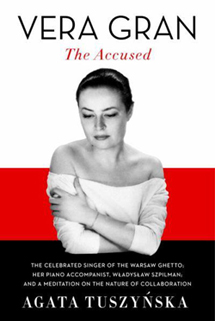

She was a star in prewar Poland, a beautiful singer with a deep, seductive voice. Like almost all of the talented, celebrated artists of her time and place, she has been forgotten. For so long, the victims of the tragedy that was inflicted on Poland were a faceless, grey mass but recently, decades later, a new generation is rediscovering the vivacious, colourful, intriguing personalities whose lives were destroyed. Szpilman, Skarbek, Norblin, Gran – to name a few.

Vera Gran is the subject of a biography bearing her name, subtitled The Accused. A brief summary appears on the cover of the book: The celebrated singer of the Warsaw Ghetto, her accompanist Władysław Szpilman, and a meditation on the nature of collaboration. From the cover alone the reader knows this will not be a portrait of the artist, not at all a biography in the usual sense; it will dwell on the accusation, on the accused, and thus, unavoidably, on her accusers.

This is a disturbing book, not just because it tells a harrowing tale but because it does so to no purpose. No new evidence is uncovered, nothing is resolved; the architects of this tragedy – the Germans – are largely absent from the story while their victims, now cast in the roles of accused and accusers, remain caught in their tormentors’ demonic script.

Within months of the German conquest, Gran, like the rest of Warsaw’s Jews, was forced out of her home and into a newly created ghetto, a self-contained city of misery rarely entered by the Germans, where Jews were forced to administer their own destruction. Even in these conditions, they tried to create some semblance of normal life: teachers continued to teach in secret schools, rabbis conducted secret prayers, doctors worked in hospitals albeit with no medicines, and cabarets offered temporary respite from the harsh reality.

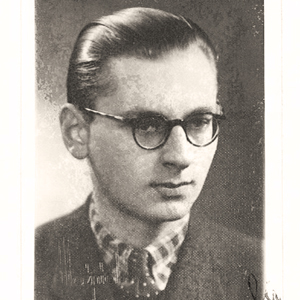

During Gran’s time in the ghetto, she performed at the Sztuka café, a surreal experience: doomed performers entertaining a doomed audience. The Sztuka hired the best-known artists and was frequented by the ghetto’s richest Jews, while they still had money. Accompanied by Władysław Szpilman, the pianist of Polanski’s The Pianist, Gran was appreciated as a star, sometimes in demand for private parties. It was one such engagement that led to her postwar troubles: she sang, it is alleged, for collaborators and the Gestapo.

In 1942, the Germans began the deportations to the Treblinka death camp, tens of thousands at a time. Money was no longer of any value; it could not buy life. However, connections with the outside could be useful and it was at this time that a young doctor, Kazimierz Jezierski, was able to help Vera get out and provide her with a number of safe houses among his friends until he himself could take her to a village where he worked as a doctor, and she spent the rest of the war as the doctor’s wife. By this time, her mother and sister had already been taken to Treblinka. Also about this time, her accompanist, Szpilman, also made it out of the ghetto. Their paths would cross again.

The end of the war in Poland was not a scene of joyous celebration; no handsome sailors and pretty young women kissing on the bridges of Warsaw, assuming some bridges were still standing. The population was emaciated and traumatized, desperately searching for missing family. For the majority of Jews there would be no returning families, indeed no returning communities. Survivors formed The Central Committee of Polish Jews to assist the survivors, but also to deal with collaborators.

When Vera Gran returned to Warsaw, she hoped to resume her life, to get back to her singing career. She sought out her accompanist, Szpilman, by then working for Polish Radio, to ask him for work. “You are not dead?” he said, and then rejected her on the grounds that he had heard she was a collaborator.

She turned to the Committee’s tribunal hoping to clear her name. Instead, she was arrested, brutally interrogated, imprisoned in terrible conditions. In the end, she was let go, but rumours of collaboration were to stalk her for the rest of her life.

Nothing was ever proven and her ordeal was reminiscent of a witch-hunt, even being once told to “self-accuse.” She herself recalled that the country was in the grip of paranoia – not surprising to any student of that most terrible of wars. The occupation had divided the conquered, not just the usual “divide and rule” meaning setting ethnic, religious or political groups against one another, but much worse than that, pitting one life against another. Every advantage gained was at a disadvantage to another.

Gran felt she was used as a scapegoat, her accusers deflecting attention to her, away from themselves. Her special resentment was against her accompanist, and she didn’t hesitate to accuse him of collaborating in order to escape himself.

And therein is the problem with the book. Must the victims still be set one against the other? Must we continue to humiliate them? The Nazis had already done that; no need to attract new voyeurs.

Tuszynska revived the memory of Vera Gran, and that’s good; Gran didn’t deserve to fade into oblivion, and her photographs reveal a stunning, almost mysterious beauty. But the author did not tell the story of the artist. She invaded Gran’s privacy, stalked her, forced herself upon her, and then exposed her in her diminished, fragile state, emotionally and mentally exhausted, confused and paranoid. None of this adds anything to the essence of Vera Gran’s life.

Tuszynska revived the memory of Vera Gran, and that’s good; Gran didn’t deserve to fade into oblivion, and her photographs reveal a stunning, almost mysterious beauty. But the author did not tell the story of the artist. She invaded Gran’s privacy, stalked her, forced herself upon her, and then exposed her in her diminished, fragile state, emotionally and mentally exhausted, confused and paranoid. None of this adds anything to the essence of Vera Gran’s life.

That said, Tuszynska seems sympathetic, and she raises important questions about the nature of collaboration, the limits of endurance, the moral dilemma posed by extreme conditions. These are questions worth pondering, a departure from the all too common simplistic accusations and judgments.

The author, a poet and biographer of Isaac Bashevis Singer, quotes Singer at the front of the book: What is fate? It’s the traps we set for ourselves. There is much one can quote from Singer but this, for a book about the German occupation of Poland and, especially, the Warsaw Ghetto? A trap we set for ourselves? No.

CR

Thank you Irene and Tecia for yet another story of pre-war Polish life I didn’t know about. It strikes me, having examined and explored my father’s family life in Poland until their deportations to Siberia, that the phrase “Let he who is without sin cast the first stone” is never more apposite than in the Polish wartime context. Those of us who were not there cannot possibly imagine the pressures, the circumstances, the grief and hatred and anger and fear that must have enveloped the country.

I am very grateful to you for the review, and for the reflective tone you take towards the book, its author and the subject herself.

Keep up the good work.

Martin Stepek

Author, For There is Hope, Fleming Press

Andrzej Szpilman, the son of Wladyslaw Szpilman, has successfully sued the author for defamation of the memory of his father, and other lawsuits are pending. The talents of Vera Gran as a singer are one thing, her tragic life another, but her hallucinations and sick accusations should have never left the tape recorder of the journalist. What a wasted opportunity to tell the story and accuse the real criminals: Nazi Germany with all the Nazi Germans.

Some truly fantastic information, Glad I detected this.