Helena Modjeska, c. 1893, in costume for “As You Like It,” complete with spear

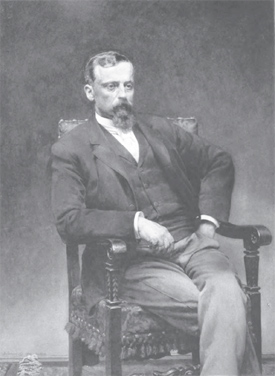

CR is delighted to publish this excerpt from The Tosspot and the Diva, a forthcoming book by San Francisco-based journalist Lynn Ludlow, and researcher and writer Maureen Mroczek Morris. The Diva is Helena Modjeska (Modrzejewska), the great Polish actress who began her American career in San Francisco in the late 19th Century. The Tosspot is Rudolf Korwin Piotrowski, a valorous captain in the November Uprising of 1830-31 in Poland. A leader in San Francisco’s lively community of Polish exiles, he is a hard-drinking patriot noted for his girth – and mirth. In 1863 he was a key figure in founding the Polish Society of California, which celebrated its 150th anniversary on November 9, 2013, at the Fairmont Hotel in Captain Korwin’s adopted city.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

As aesthetes and intellectuals from the salons of Kraków and Warsaw, the would-be yeomen know a lot about the Brook Farm commune in Massachusetts.

As farmers in Orange County in 1876, they don’t know a rootstock from a rooster.

The bewildered Poles don’t speak much English. Nobody advises them that Utopia, like the long-gone Brook Farm, is another way of saying Never-Never Land.

“The commonplaceness of it all was painfully discouraging,” says a new arrival at the tiny commune planted in Anaheim amid a colony of industrious farmers from the Kingdom of Bavaria. As Helena Modjeska, she will add in her autobiography “the front yard, with its cypresses, shaggy grass, and flowers scattered at random, looks like a poorly kept small graveyard.”

Helena Modjeska, c. 1889, in costume for an unidentified play

Back in Poland, she is Helena Modrzejewska, the famous tragedienne. In Southern California, the name draws attention only because neighbors have trouble pronouncing it. Just turned 37, she is no longer the stage star who sailed away from her brilliant career in Warsaw to begin a new life in the pastoral Santa Ana Valley. She is 8,000 miles away from back-stabbing rivals, Russian censors, and a debilitating illness. She is now Mrs. Chłapowska, the cook.

The utopian venture will be called a “colony.” The word needs stretching for four men, two women, two small children, a teenaged maid, and a 14-year-old lad. They occupy a two-room house on forty-seven acres. It fronts on Center Street, then the main street of Anaheim. When the village is incorporated the same year, the polyglot population is listed as 881 – German-speaking Bavarians, Spanish-speaking Californios, more than one hundred Cantonese-speaking laborers, and the Polish-speaking newcomers who arrive with soft hands for hard work.

After a few days of planting vineyards and digging plots for vegetables, three of the Poles find reasons to do something more cerebral. The hammock is seldom empty. Someone else must open the irrigation gates, sow the seeds, feed the stock, and shoo the crows. The chores fall to Helena’s husband, Karol Chłapowski, the aristocrat who invested his savings in the commune, and Rudolf, the teenage son of his wife, Helena. (He will someday be known to the world as Ralph Modjeski, the bridge builder and chief engineer for the San Francisco Bay Bridge.)

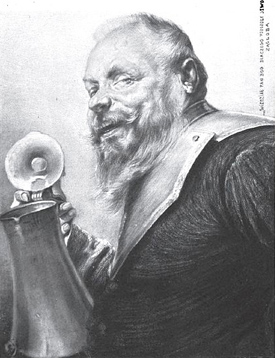

Painting of Henryk Sienkiewicz by Kazimierz Pochwalski, c. 1898

In the tack room of the barn is the bedroll of Henryk Sienkiewicz. With “Litwos” (Lithuanian) as his byline, the aspiring author writes travel pieces for the Gazeta Polska back in Warsaw. They represent the commune’s first cash crop. He will return to Poland and eventually win the Nobel Prize for literature, but his fame begins there with his Trilogy of historical novels. The first, With Fire and Sword, introduces a Falstaffian anti-hero, Jan Onufry Zagłoba.

Polish scholars generally agree that the fictional fat knight is inspired by Captain R. Korwin Piotrowski, an exuberant leader in San Francisco’s vigorous community of Polish exiles and émigrés. Curious about how the Polish intelligentsia cope with the new world of the New World, the fun-loving behemoth sends word that he will visit the commune.

The guest is a catalyst.

A sketch of Rudolf Korwin Piotrkowski by Henryk Sienkiewicz

“The captain arrived next morning, and with his entrance gloom changed into merriment,” Helena recalls. “Everyone smiled and talked, and all at once became witty and entertaining.”

Korwin impresses Henryk and Helena with his charm, wit, stories, and Polishness.

“Piotrowski was a curious type,” says Helena. “ He seemed suited rather to the 16th or 17th century than to our modern era. His humor reminded me sometimes of Sir Toby Belch or Falstaff.”

Karol Chłapowski calls him “the finest type you can imagine of the conservative old country squire whom you meet today only in stories.”

On the one hand, Helena says the colorful expatriate is “a strange combination of old-fashioned [Polish] culture and modern American notions of politics and business.”

On the other hand, she never forgets his notion of a Polish greeting.

“…(H)e opened the kitchen door, and seeing Anusia, the maid, exclaimed, ‘Halloo, pretty maiden!’ Then turning to us, he said, with a wink, ‘Where did you pick up this dainty?’ When we told him that we brought her with us from Poland, he laughed. ‘Oh! If she is a Pole, I must give her a Polish greeting!’

“With these words he entered the kitchen, and almost at the same time we heard a shriek, a slap, and Anusia was running away into the yard, while the captain was standing at the kitchen door, holding his sides and laughing.”

Helena immediately thinks of Sir John Falstaff, Shakespeare’s hefty amoralist. The same thought occurs to Henryk, but it will wait.

Two characters from Henryk Sienkiewicz’s “With Fire and Sword” in an 1884 painting by Juliusz Kossak: Pan Zagłoba, left, and Bohun, right

The merriment fades when, on the first night of the captain’s visit, Mrs. Chłapowska’s guest bed is flattened by “his colossal frame.”

It’s an omen. Poor decisions, bad luck, and lofty discourse will soon flatten Brook Farm West.

Korwin takes his blankets out to the barn, a crude bunkhouse for Henryk and the artist Łucjan Paprowski.

A few days later, Henryk saves the captain from death by drowning.

Helena quotes Korwin:

“When I was at a short distance, I saw Anusia in the yard, hanging up linen, and I called jokingly, ‘Now, my little bird, I will catch you and kiss you!’ To my astonishment, the girl did not run away, but called back, ‘Come, come, captain, kiss me!’ The imp knew of the ditch separating us, but I had only my foolish fun in the head, and the girl looked quite pretty. Besides, I could not see the ditch, as it was all overgrown with weeds.

“I clapped my hands and started on a run, when suddenly – O Maria! Joseph! Shall I ever forget the sensation? I sank plumb into the cold water up to my hips. I tried to get out of the ditch, but this confounded soil of Anaheim is genuine quicksand; the more vigorous were my efforts, the deeper I sank.

“I called to that little demon of a girl to help me or to call someone, but that incarnation of imbecility only laughed more and more, while I was sinking lower and lower.

“When the water reached to my armpits, I gave up the struggle.

“ ‘Perish will I and my fleas with me!’ ”

Henryk, who had been in the barn, puts down his pen. He rushes to save the life of the bellowing Don Juan.

“I raised my eyes, and my hopes revived,” says Korwin, “for he was extending his hands to lift me up, which, however, considering my weight and his slender form, was almost impossible.”

Henryk manages nonetheless to pull from the quicksand the captain’s 275-pound bulk. It’s a double rescue. No Korwin, no Zagłoba.

“Pan Zagłoba” by Piotr Stachiewicz in an 1898 Henryk Sienkiewicz Jubilee Album

Although a fictional character, the 17th Century patriot lends his name even today to pubs, inns, and restaurants in Poland and the Polish diaspora. His image appears on labels for lager and liquor. Henryk’s Quo Vadis was an international best seller, but the Trilogy is said to be as popular as the Bible in many a home in Poland.

To Helena, the incident in the bog turns into yet another reason to quit the commune, to restart her career in San Francisco, and to become, as Modjeska, one of the great actresses of the Golden Age of Theater in America.

To Korwin, it turns into a delicious, self-depreciating anecdote.

To Henryk, it turns into a memorable line he will someday give to Korwin’s doppelgänger in With Fire and Sword.

“This is the end,” says Zagłoba. “I’ve had it…And so have all my fleas!”

CR

I absolutely love this excerpt. What a cast of characters! From my beloved Helena Modrzejewska and the delightful Korwin to the quieter (and v. handsome!) Henryk Sienkiewicz. Am v. much looking forward to the book.

Pingback: Don’t Call It Frisco

Pingback: Welcome to Summer 2015!

Pingback: 1905, A Very Good Year