WARSAW, Poland – There is no better place than the College of Europe in Natolin, Warsaw, to discover what others think about Poland. Founded as a sister campus to its Bruges counterpart in 1992 in response to the revolutions of 1989 and in anticipation of the European Union’s Eastern enlargement, Natolin hosts a diverse, fly-in faculty who cannot stay indifferent to the country’s rich and complex history.

WARSAW, Poland – There is no better place than the College of Europe in Natolin, Warsaw, to discover what others think about Poland. Founded as a sister campus to its Bruges counterpart in 1992 in response to the revolutions of 1989 and in anticipation of the European Union’s Eastern enlargement, Natolin hosts a diverse, fly-in faculty who cannot stay indifferent to the country’s rich and complex history.

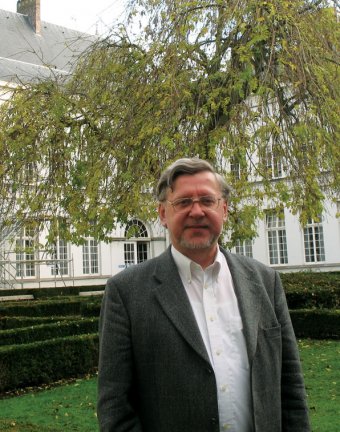

This renowned faculty includes Marc Maresceau, a law professor and the director of the European Institute from the University of Ghent in Belgium. I followed a 12-hour course he gave on European Neighbordhood Policy in Natolin. As a young man, he held the chair of European Law at Ghent. “But I wanted to do something new, something related to external relations,” professor Maresceau explained to his students. “I was faced with the new situation of the arrival of Gorbachev in 1985. This was a breaking point for the European Community. After a couple of weeks, I was an expert on this subject, because nobody else was writing about it.”

Between ’86 and ’94, professor Maresceau traveled to Moscow 20 times and also paid visits to the countries that used to be behind the Iron Curtain. “I visited Poland and Hungary in ’86-87. In Budapest, everything was booming… during the same period, Warsaw was very gloomy, dark, wet. In Hungary, everything was so colorful: I remember butcher shops, sausages … [those are] impressions I will never forget. I learned how different the countries of the COMECON were,” he recalled during the class.

I was delighted to hear the impressions of a Western European scholar about his visits to the European East. Nevertheless, something struck me as odd during the class, and it was the mention of the 1683 battle, when the Turks of the Ottoman Empire were at the gates of Vienna. (Please see the top left corner painting by Józef Brandt, “Return from Vienna“.) A crucial piece of information was not revealed: the decisive role of Jan Sobieski’s army in this battle.

It seemed this information is only crucial to the Poles. Professor Maresceau himself mentioned this date is not well-known in Western Europe. He proceeded with the course, and later he mentioned how disappointed he was in Poland’s attitude after it joined the European Union in 2004. “In the 90s, Poles would have sold their soul to the devil [to join]. But once they are in, the spirit is not there,” he said.

For me, the link between Poland’s lack of positive spirit and the lack of acknowledgement of Poland’s place in European history is clear. It does not justify it, but it does provide a clue as to why Poles act the way they do in international relations.

Nevertheless, Professor Maresceau and I happen to share a common passion for the Ottoman Empire. I’ve been to Turkey three times and am planning to move there in the near future. He owns 500 books on the subject. I proceeded to engage in conversation about Polonezköy (or Adampol), a Polish settlement established in the mid-18th century about 40 km outside of Istanbul by Michał Czajkowski (who took on the name Mehmet Sadyk Pasha) at the invitation of the Sultan.

To my surprise, the settlement was unknown to my professor, and he gladly accepted documentation on the subject. In the evening, in the company of a small bottle of Chateauneuf-du-Pape, we engaged into a fruitful conversation (sometimes punctuated by disagreements) about the causes of Poland’s attitude in international relations. After a few years of approaching any talk of Poland in very emotional fashion, I’ve realized the only way to set aside prejudice is through dialogue, not confrontation. Besides, professor Maresceau admitted he wasn’t an expert about Poland.

Here are a few excerpts from our candid conversation.

CR: At CR, we like learning from the past to build a better future. My generation is not afraid of criticizing our own country, but this criticism must be constructive and lead to change.

Earlier you spoke of the 1683 battle for Vienna, yet you failed to mention the decisive role of Poles in it. This is a tendency among scholars from what is often called “Old Europe.” It seems there is a strong link between this lack of acknowledgement of the role Poland has played in European history – you mentioned yourself most people from Western Europe are unaware of the 1683 battle – and this “lack of community spirit” in EU matters you mentioned.

M.M.: The point I wanted to make was not why and how it came to the fact that the Ottoman Empire was unable to be successful in its siege before the gates of Vienna. It was just mentioning a fact of European history… [In this sense], 1683 is an interesting date … to show that the Ottoman Empire had a European past. If I wanted to mention [why the Ottoman Empire failed to take Vienna,] then of course I would have to mention Sobieski and the role of Poland. … From this point of view, it may seem disappointing that I didn’t want to get into this discussion. I just wanted to make the point that the Ottoman Empire had a European past and its positive and negative dimensions about it. Nothing more and nothing less.

M.M.: The point I wanted to make was not why and how it came to the fact that the Ottoman Empire was unable to be successful in its siege before the gates of Vienna. It was just mentioning a fact of European history… [In this sense], 1683 is an interesting date … to show that the Ottoman Empire had a European past. If I wanted to mention [why the Ottoman Empire failed to take Vienna,] then of course I would have to mention Sobieski and the role of Poland. … From this point of view, it may seem disappointing that I didn’t want to get into this discussion. I just wanted to make the point that the Ottoman Empire had a European past and its positive and negative dimensions about it. Nothing more and nothing less.

Certainly, I had nothing to say about Poland’s role in the preservation of a Christian Europe. That was not the point I wanted to make [alhough this is another] dimension of what was at stake in the siege of Vienna.

CR: Earlier during the course you compared the COMECON to the Marshall Plan, a comparison some historians have a hard time with. I quote: “Stalin’s COMECOM did not even vaguely compare to the Marshall Plan. The Europeans have never really acknowledged what the Americans did for them after the war, and how lucky they were compared to the countries under Soviet domination. Stalin’s policies ensured prolonged poverty; the Marshall Plan rebuilt Europe and ensured prosperity.” (Historian Irene Tomaszewski.) What is your reply to this?

M.M.: I agree with the starting point; that the American Marshall Plan was very good intervention of the American government towards Europe in terms of the aid which was given to reconstruct Europe. [It] forced the Europeans to work together in order to truly benefit from the plan. This was at the origin of the OECE (Organization for Economic Cooperation in Europe): the predecessor of the OSCE (Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe).

This element is not known enough in the history of the European integration process. It precedes the European Community initiatives, the ESCE (European Coal and Steal Community) Treaty: this was the second half of the forties. The OECE is, I think, probably the biggest result of the Marshall Plan [and] lead to the creation of the COMECON as a reaction by Stalin … Of course, later we referred to the Marshall Plan as an inspiration for many transition initiatives in Central and Eastern Europe, but they never had the same dimension and considerable financial results as the Marshall Plan did.

It’s quite fascinating to that the roots [of this] were in the Americans. These attempts to cooperate involved countries that had been enemies a few years earlier. It’s important to underline this in European World War II history.

CR: In its form as the 4th Republic (as a country which became truly independent in 1989, after a German occupation and decades of Russian domination) Poland is still a young, consolidating democracy. How do you think this impacts on its position within the EU?

It’s difficult to assess (…) A lot depends on the quality of the political leadership. Sometimes, countries can have an impact on decision-making at the EU-level which goes far beyond the importance of the country on the European continent. (…) I think it has nothing to do with the quality of democracy, whether it is young or old.

On the whole, you see a kind of decline (… ) of great leadership in the EU. This has nothing to do with old or young members. (…) So your question, to link that with new democracies, I don’t this is a point of reference for me. Leadership quality is disconnected. It’s not because you have a new democracy that you have good leadership.

CR: On the contrary. If a country is a young democracy, then it is natural that the political elites don’t have much experience in ruling in a democratic setting. Poland has still much to learn about [modern] democracy, because it regained its independence only in 1989. It’s current constitution was drafted in 1997.

M.M.: (…) When you apply to join something which is there already, then you should be willing to accept the learning process. You have to absorb some practices and rules; institutional behavior. This is a signal I didn’t see from Poland. This was a disappointment for me. (…) I had the impression that Poland became rather isolated in this [EU] construction, and it wasn’t good for the country.

From an economic point of view, Poland did very well (…) But Poland could have much more weight … if it was a bit more willing to play the game, to influence… instead of the chaos it has created. For example, the last institutional thing that happened with the Prime Minister and the President at the last summit: the recent [quarrel] about who is going to represent Poland at the European Council and then to fight it in front of the camera, … people are laughing at that. This doesn’t help to reinforce the position of Poland at the EU level. It’s also a signal of a certain lack of maturity. This is a thing I was resenting. I found this disappointing. This is my personal opinion.

[But] I’m sure each Member State will learn by having all kinds of experiences.

… Whether you are a new democracy or not, when you join the EU, you should expect a certain willingness to join the game. If not, I ask myself, why do you join? …

… We must be very careful not to fall in the trap … to revive the demons of the past. I’m the last one to participate in this.

I prefer a cosmopolitan attitude. This is just the opposite of nationalism: trying to benefit from different cultures. Someone who is cosmopolitan has a broad view. This was something that was demonized – this cosmopolitan approach. You need knowledge of history to be a true cosmopolitan, because then you are equipped to take the good parts of various cultures, to understand other cultures; to accept them, to live with them. From this point of view, the cosmopolitan approach, I like it very much. Congratulations on the title of the review.

I would like for your message to reach the political leadership. (… ) I think it would be much better to have a cosmopolitan leadership. If I were Polish, I would support you very much.

(…) I remember my first activities under the communist period. I had Polish researchers coming in. I was always astonished by their enormous dynamism, and openness and willingness to move forward. This is one of the very good things I have experienced in Poland at various levels. That’s something I didn’t see elsewhere. That makes my disappointment even a bit stronger: that certain acts of the political leadership, knowing these genuine positive characteristics [of the people], and not seeing them in the official policy on the ground.

But I’m just a foreign observer, not an expert on Poland: it’s not the country I know best in Central and Eastern Europe. … I may be wrong in my perceptions.

Although professor Maresceau and I had fundamentally different perceptions about the level of development of democracy and the attitude of a given country in the European context, I’m sure we left understanding each other a bit better. I personally believe there is a clear link between the level of polical maturity (or immaturity) and the quality of democracy in European countries. Professor Maresceau did not accept this assertion as a starting point.

However, we agreed on the most important aspect of the dialogue: cosmopolitanism is absolutely fabulous.

CR

Imagery

“Return from Vienna” painting by Józef Brandt. The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth army returns with the spoils of war after defeating the Ottoman Empire forces attacking Vienna during the 1683 Battle of Vienna.

Wonderful article! We will be linking to this great post on our website.

Keep up the good writing.