Mount Kilimanjaro’s Kibo Summit

PHOTO: Yosemite

MONTREAL/TANZANIA – In 1949, four years after the end of the Second World War, a Canadian member of the UN’s International Refugee Organization (IRO) boarded a plane in Germany to fly to Tanganyika (now Tanzania) British East Africa to evaluate a group of refugees – Polish, he was told – as prospective immigrants to Canada.

Until this time, the IRO official, a Mr. Sharrar, had been working on repatriation and resettlement of refugees in war ravaged Europe. What, he wondered, were these refugees doing in Africa, and why would they not agree to repatriation?

It was a long flight from Europe to Africa in those days, necessitating a stopover in Beirut where, in any case, he was to meet another group of recalcitrant Polish refugees. That done, he then flew to Nairobi where arrangements had been made for the rest of his journey by train to Arusha in Tanganyika, and then by jeep to Tengeru, as the refugee camp was called.

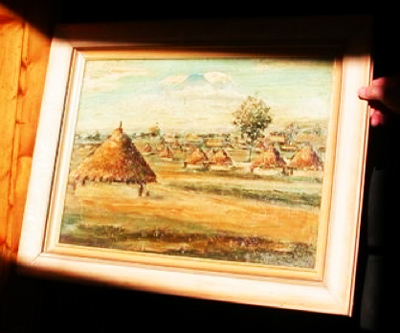

The Tengeru settlement was situated at the foot of Mount Meru, with Mount Kilimanjaro glistening in the distance. It was quite large, at its peak home to 5,000 people, though by 1949 this population of mostly women and children was quite diminished. They were housed in traditional native huts – round, whitewashed mud huts with thatch roofs, an earthen floor, one window, one door – incongruously set in European-style flower gardens within neatly trimmed hedges. By this time, a few people managed to have square houses built for themselves, but still of the same mud construction with thatch roofs. But square. Conventionally, reassuringly, square.

And so it was that the Canadian Mr. Sharrar had travelled a great distance to come to a refugee camp only to find himself in a Polish “settlement.” He would have preferred “camp,” perhaps fenced, as indeed had some of the colonial officials, especially those in the security branch, on the grounds that a little barbed wire makes for good order. But the Poles would have none of that.

Instead, Mr. Farrar’s tour of the settlement took him to schools – elementary, a gimnazjum, a lyceum, and a technical school; a YMCA with sports and recreational facilities, and a reasonable library; a cinema covered by a roof on stilts but without walls; and an open-air theatre. There was a co-op bakery, and a co-op store sold a modest supply of sundries along with foodstuffs from the settlement’s impressive farm. Established in order to make the settlement as self-sufficient as possible, the farm accomplished this with great success, combining crops native to Africa as well as – climate permitting – old favourites from Poland. Indeed, after the Polish refugees left, the farm became first an agricultural college and ultimately The Horticultural Research and Training Institute of the Department of Research and Development of the Tanzanian Ministry of Agriculture. Some of the original houses and schools are still standing, a monument to sensible, economical design. A final stop on the tour perhaps would have been to nearby Lake Duluti for a swim in its cool, clear waters.

Tengeru, snow-capped Kilimanjaro in the distance, painted by an itinerant artist soon after the first refugees arrived.

The distinguished guest met the children, smartly outfitted boys in crisp white cotton shirts and khaki shorts, and girls in perfectly pressed white dresses with navy sailor collars. The children treated him to a concert, the settlement’s leaders to a banquet. Some of them, according to a horrified Mr. Sharrar, actually wore evening dress. What was he to make of this strange European matriarchy living in mud huts set in European gardens with trimmed hedges – in equatorial Africa?

Alas, this did not make a favourable impression. Appalled by this ostentatious display of well-being, the Canadian promptly informed his superiors to that effect.

“Displaced persons in East Africa live a life all their own…” wrote John A. Sharrar. “It was fantastic for an observer who has visited almost all camps of displaced persons throughout Europe and who knows of their extreme misery and anxiety to end their present life, to participate in a Polish party in the heart of Africa.” The evening dress must have been the last straw. Let’s have another look at Mr. Sharrar’s report.

The Canadian IRO team interviewed 1,324 prospective immigrants but accepted only 463. “The persons accepted by us were without doubt the best available,” the report continued. “The others are content to lead their life of leisure, with most of the manual work being done for them by native Africans. The only exception is a locally operated dairy farm to which some refugees contribute by a few hours work each day.” He went on to comment, equally unfavourably, about the Polish refugees in Lebanon, on the one hand longing for their former homeland and on the other, totally uncompromising about repatriation to a communist Poland ruled by Moscow.

He made no mention of the fact that these Poles had once been prisoners in the Soviet Gulag, which might have explained their refusal to entrust their lives to a regime imposed by Stalin. Perhaps Mr. Sharrar didn’t know that; perhaps it was of no interest to him. Concluding his report by saying one ought not generalize, he then generalised liberally, insisting that his unfavorable opinion was based on personal observation.

This report was forwarded to the Canadian labour representative in Germany, an official not from the department of immigration, since no such thing existed at the time, but from the Department of Mines and Natural Resources, which provides an insight into the hearts and minds of the people who worked on the immigration policy of the time. Copies of the report were sent elsewhere, among them to another IRO official, a Mr. M. S. Lush, a special advisor on the Middle East. Mr. Lush, alarmed by this unfavourable report, immediately wrote to the IRO chiefs of mission for Beirut and Nairobi, with a copy to the Ottawa Mission chief, suggesting that the Poles be told that looking too good was not the way to an officious bureaucrat’s heart.

Mr. Lush pointed out several “half-truths” in the Sharrar report. He suggested that the large number of applicants indicated that these refugees were quite willing to relocate and start their lives anew and that perhaps they were viewed unfavourably for the wrong reasons. “I am sure Mr. Sharrar would not wish the lot of the refugees in East Africa to be reduced to the barely tolerable conditions of their fellow sufferers in Europe [and] no one would wish a refugee’s desire to resettle to be induced by the misery and discomfort of an IRO camp.” Mr. Lush was rather understanding of the Poles’ dreams of a “Polish renaissance” and quite approving of their lifestyle. “I rather like to see refugees in these camps who take a pride in their appearance and turn out themselves and their children decently and perhaps even smartly.” He conceded, however, that the Poles should have realized that this would not make a good impression on visiting teams and suggested that “…we must try to change their attitude, not by cutting down their clothing and rations and issuing them with sackcloth and ashes but, as the General Council resolved recently, by continual and urgent counselling.” It was also explained that hiring native labour was not a matter of living a “life of leisure.” Quite simply, these refugees were mostly women and children. Hiring men for heavier manual labour was quite natural under the circumstances.

A flurry of letters followed. A Mr. Jacobsen, the Assistant Director General for Repatriation and Resettlement in Geneva wrote to the Ottawa Mission chief, Wing Commander R. Innes, explaining that while the Poles did not live in the stern conditions of a refugee camp, neither were they living in the lap of luxury. Indeed they deserved credit for doing so much with so little.

As for the refugees in Tengeru, wrote Mr. Jacobsen, “To be disgusted by seeing refugees who take a pride in their dress, and to compare them unfavourably with others who in Germany have not had the opportunity, shows lack of perspective. Had they been dressed in rags and looked dishevelled, Mr. Sharrar might well have asked why, in the delightful surroundings of Tengeru, the refugees could not smarten themselves a little.” That said, he extended warmest regards to Mr. Sharrar and the Canadian Mission.*

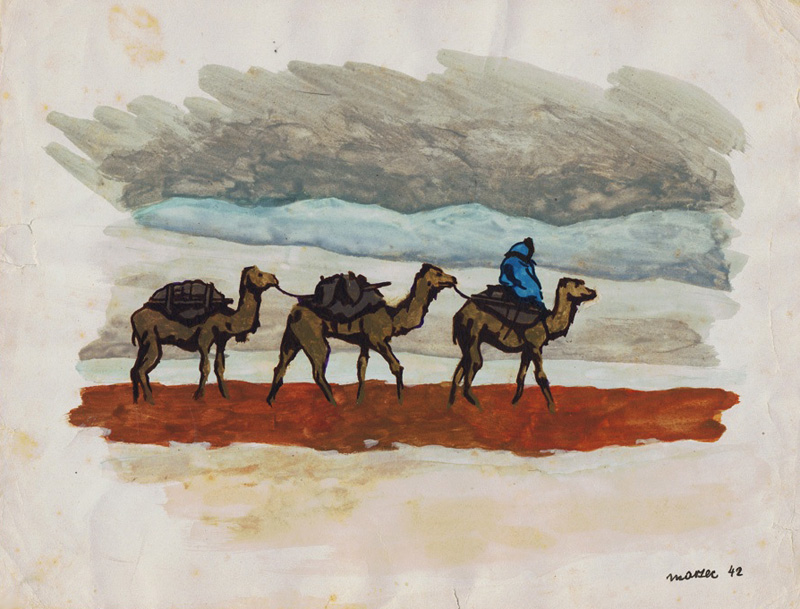

The Polish refugees were eventually accepted as immigrants in various countries, Canada included. The author of this article had spent almost seven years of her early childhood living in “the delightful surroundings of Tengeru,” and much longer researching the story of this most remarkable children’s odyssey, from Poland to the USSR, across Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Iran, India, Africa and the Middle East, Mexico, finally settling in England, Canada, the United States, New Zealand, Australia, or Argentina. The travels of Odysseus pale by comparison.

Along the way the refugees’ lives were touched by a cast of characters that included the Shah of Iran, the Viceroy of India, two maharajas, British diplomats and military officials, American relief agencies, Red Cross organizations of various countries, the Polish and International YMCA, the international scouting organization and charitable institutions in England, Canada and the United States; by soldiers and officers, colonial officials and their wives, Americans and Englishmen, Hindu and European doctors; and by ordinary Persians, Indians and Africans, Muslims and Christians, some of them rich, most of them humble. About this last group, the “ordinary people” whose languages, cultures and appearance were so different, neither contemporary records nor the much later recollections reveal that they were anything other than kind and friendly, these qualities mixed with a natural and mutual curiosity marked by openness rather than suspicion. Admittedly, and unfortunately, their contacts were limited. The attitudes at the official level, as this story shows, revealed the whole range of human responses from compassion to indifference, sympathy to hostility, pettiness to generosity, condescension to respect.

The Polish Government-in-Exile in London and the Polish army in the Middle East were, in many ways, the most important factors in the lives of the refugees. While powerless to help their people in occupied Poland and, except for a short time, in Russia, in those parts of the world that were ruled by law, they provided the refugees with protection much like parents provide protection to children, ensuring they had the means to live decently, interceding on their behalf, planning for their future, and insisting they be treated with dignity.

It is a story that remains to be told.

CR

* All quotations are from documents from the National Archives of Canada in Ottawa. This article is an excerpt from a book on this incredible journey, a work in progress.

Pingback: February 1940: Exile, Odyssey, Redemption

Pingback: The Africa Connection

Ridiculous how people can react, instead of saying “well done – you have done miracles to be self-sufficient and to live a “normal” life after the hell you’ve gone through in Siberia” Sharrar critizised them for their achievements! I was born in Tengeru and know from my Mum how proud they were of their schools. My mother was the teacher responsible for all the handicrafts, embroidery, sewing etc. other articles sold to raise money! I have photos of the handicraft shows at the camp!

Sharrar didn’t understand the Polish character of survival and pride in themselves. He should have praised them for their achievements instead of critisizing them. They became self sufficient by working hard. If they used the locals to help them, the locals were paid. My father run the camp canteen, cinema, butchery etc. under Col. John Minnery. My mother was the teacher responsible for all the handicrafts sold by the school to raise money.