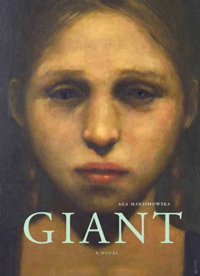

Giant

Giant

By Aga Maksimowska

Pedlar Press, 2012

The postwar veterans I grew up among would raise their eyebrows, raised like ironical quotation marks and call them “the new generation”. That was their descriptor for Polish émigrés arriving in North America between the 1981 declaration of martial law and the triumph of Solidarity. The newcomers displayed a fondness for café au lait and included a higher proportion of artists and intellectuals than previous migrations. They came with high expectations of the west and proved adept at tapping into government assistance for community projects and personal needs. For the veterans, who had rebuilt their lives with soldierly rigour, their arrival opened a second generation gap in the community. Flower power and the secularism of the Me Generation had already divided them from many of their children; the Solidarity émigrés served unwelcome notice that the Poland they had cherished in memory had moved on as well. To baby boomers like me, the conflict was an old-world grudge match that I was happy to dodge, and the new generation remained something of an enigma.

Which is why Aga Maksimowka’s Giant is such a welcome addition to the canon of Polish-Canadian literature, presenting, as it does, an account of the “new generation” through the eyes of its “next” generation. The story is told by Małgorzata Wasiljewski, whom we discover as an eleven year old living in a Soviet-style apartment block in the Gdańsk suburb of Morena. Gosia has lots of reasons to feel a freak: her surname has a Russian ring to it, which doesn’t escape the notice of her neighbours; the genes inherited from her decathlete father are turning her, literally, into a “giant” who towers over her peers and over most of the adults in her life; and finally, she is the child of divorce, a cardinal sin in Catholic Poland. Gosia’s father has forsaken athletics for a life at sea. Gosia’s mother Ewa, a teacher and translator, is off earning dollars in Canada, leaving her and her younger sister in the care of her grandparents.

The novel is told in first person, present-tense, by Gosia as she and her sister join their mother in the Toronto suburb of North York. Ewa works as a domestic, and she has forged a relationship with Serge, a surly Canadian academic of Polish descent. The author’s choice of a ticked off adolescent as narrator for a tale that spans eight years can be a tricky one, but Gosia is a perfect vehicle for Maksimowska’s trenchant observations as she confronts the paradoxes, myths, delusions, and necessary accommodations that have complicated Polish life on both sides of the Atlantic for three quarters of a century.

Maksimowska is no sentimentalist. Her characters dismiss Polish Canadians’ romantic views of the old country (“If you love it so much,” Ewa challenges her new husband, “why don’t you live there?”). Gosia frames the complexities of the Polish experience with breathtaking directness. Her beloved dziadek is a concentration camp survivor who despises the Germans, though he used his Aryan looks as an argument for his release. In Solidarity-era Gdańsk, he is a church-going member of the Communist Party who hates “Bolsheviks” in private, but uses his party connections to procure a separate apartment for Gosia’s mother. Gosia also adores her babcia, the classic, resourceful and inexhaustible, pączki- and gołabki-making Polish grandmother who keeps the family together—in between fits of fall-down drunkenness.

In Canada, Gosia longs for her life in Gdańsk, resents her mother for taking her away from her grandparents, but dreads any public display of her Polishness among her peers. Discussion of Solidarity’s election victory in her History class, she says, makes “me feel like I’m at the airport in Warszawa again. A giant I protruding from my giant forehead: Immigrant.” She also loathes speaking Polish in school: “They might as well give me tiny cymbals and chant, “Dance, monkey, dance!”

Nor does Maksimowska flinch from the more loaded historical issues facing present-day Poland and the Polish diaspora: the holocaust , anti-semitism, and the distorted perspectives these phenomena have bred. “He didn’t much like the Jews, a sentiment he had in common with the Germans,” Gosia says of her grandfather. “But he also didn’t much like that the Nazis put their camps, prisons, and torture chambers in Poland. ‘Do your own dirty work,’ I remember Dziadek sneering.” In Toronto she suffers the prejudices of classmates who think Poland culpable for the holocaust, and suspects that her crush on a Jewish boy is rebuffed because she is Polish.

A gawky teenager’s self-consciousness becomes an apt metaphor for the immigrant psychology, and for the coming-into-awareness of a misunderstood nation. Maksimowska deftly touches all the bases. At a slight 211 pages, the novel left me hungry for more. The good news is that Maksimowska is just getting started and we have much more to look forward to.