Białowieża Forest

By Yapo

The Kresy – an area of Poland dominated by the great forest of Białowieża, where the ethnic diversity was as diverse and as natural to the landscape as the flora and the fauna of the forest.

It is the forest that gives that area of Poland known as the Kresy its magic and its mystery. The forest bed emerged when the glaciers retreated to their original site in the mountains of the North after the last ice age in Europe leaving behind a network of small rivers and subterranean water reserves that nourished this vast plain lying 170 metres above sea level in the northeast of Europe. It was not long – not long, that is, when time is measured in eons – before this plain gave birth to a forest of indescribable beauty.Once covering a vast tract stretching from the Baltic to the foothills of the Carpathians, it remains, though diminished, the last reserve of primeval forest in Europe.

There are no great mountains, big rivers or vast lakes there. The forest’s beauty lies not in spectacular vistas but in its enduring, life-giving, breathtaking diversity, containing within it both the leafy forests of Central Europe and the evergreen coniferous taiga of the steppes of Siberia, along with species from the Mediterranean as well as from mountain regions. There are 1.5-metre wide, 40-metre tall pines; 50-metre high spruces; and oaks three metres wide 40 metres high. Ash, birch, enormous lime trees, fragrant lindens, larch and alders form a canopy for shade-loving plants; perennials abound, mosses cling to the trees, bindweed twists around tree branches. Berries and ferns, mushrooms, wild garlic, wild ginger and violets cover the ground.

A network of rivers snakes through the expanse of the forest entering along shallow valleys in broad expanses of woodless peat bogs and marsh, becoming wilder as the rivers penetrate the forest before disappearing under the canopy of giant trees. Vegetation includes nightshade and countless sedges and ferns. The banks of the little rivers are concealed by dense rushes and willows. The marshland is fertile, supporting still more varieties of vegetation including hazel and blackberry.

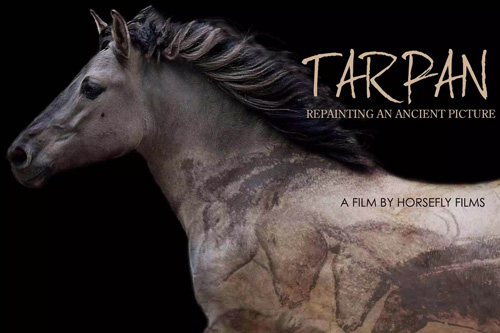

Tarpany in Poland

By GerardM

This great array of life forms a closely integrated community that has nourished, protected and revived them despite the many enemies they have faced over the centuries. The forest and the marshes are home to a multitude of animals: lynx, wolf, fox, wild boar, beaver, badger, weasel. A choir of birds fills the air: orioles, owls, grouse, woodpeckers, ducks. A herd of bison, 300 strong, thunders through forest trails and wild horses, the tarpans, though fewer in number, are slowly making a comeback. Altogether, this abundance includes over 4,500 species of plants including 3000 of fungi, and 11,500 species of animals, 8,500 of which are insects, and many rare species of mammals and birds of prey.

The forest formed the eastern borderlands of Poland back in the days when the country stretched from the Baltic to the Black Sea, from the Oder to the Urals. History has not been kind to this country which is much smaller now, as is the forest, called Białowieża, which is now bisected by the Polish-Belarus border. Still, despite the mutilation and death inflicted upon it by greed, war and wanton cruelty, the forest remains, some of it in its primeval splendour.

It is an awesome thing, this huge and ancient forest and yet, we are told, “the forest never was and never will be old. Generations of trees and herbaceous plants are born; they grow up, get old and turn to ashes in their own rhythm.” When autumn gales, summer storms and winter snows break branches and snap trunks, “the wounds gradually heal and greenery covers them again with new life.” Every so often, part of the forest burns in a lightning fire. The charred expanse, exposed to the sun, soon sprouts seedlings. Unaided, the natural reforestation produces an array of vegetation as diverse as that which was burnt. But that is only when nature dictates the rhythm of life, death and renewal; the ideas, plans and actions of men often reject the diversity and rhythm of nature. They would destroy not only life but the means to reproduce life; they would exterminate one species in order to allow another to dominate.

The great auroch, a wild ox that may be the ancestor of our domesticated cattle, exterminated in Britain during the Bronze Age and in the rest of Europe not much later, survived in Białowieża until the 16th century. Ironically, both its prolonged survival and its ultimate extinction is owed to greed and arrogance. The nobles of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth restricted access to the forest for all but their own purposes, thereby protecting it. It was forbidden to settle there, to cut the trees or to exploit in any way the bountiful treasures of the forest lest these activities interfere with the natural order within. This decree took little notice of the needs of the people who lived in the area and concern with the “natural order” in the forest extended only insofar as was needed to protect what the nobles considered their own hunting grounds. It was they who killed the last auroch, for no reason other than the thrill of the hunt, and, in time, others with the same self-importance and callous disregard for nature would destroy the bison, the tarpans, and many other animals and birds.

Castle Hill in Vilnius

Source: Archive of new records, Archiwum Jana Kwapinskiego i jego rodziny, sygn. 188, s.1.

The ruling classes exploited the forest for their own profit, delineating which part would be used for timber and which was to be preserved for their hunting exploits. In the interest of trade and commerce, they cut great trees, floated logs down the rivers and constructed mills while in another part of the forest they satisfied their love of the chase by hunting wildlife with an equal disregard for the balance of nature.

The peasantry, forbidden the right to hunt, did what peasantry has always done throughout history and everywhere. They worked for the nobles both on the land and in the mills, while secretly poaching animals for food and skins, and trees for shelter, and they picked berries, nuts, fruit, and mushrooms to supplement the little they could keep of their harvests.

Yet the poorest no less than the richest people of the Kresy have always had a boundless love and sentiment for the land that is exalted in Polish song, poetry and prose. Home to thousands of storks, their nests are treasured by people lucky enough to have storks build their homes on their property. Each year, when the storks leave for the winter, their human neighbours wait eagerly for their return, and each year the same families return to their own nests.

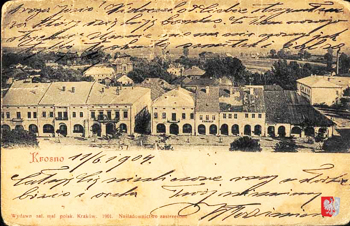

Rzeszów, ca 1900

Courtesy Kresy-Siberia Virtual Museum. Tomasz Wisniewski collection.

Magnificent though the forests of the Kresy are, the area is not all or only forest, but is dotted with villages, towns and cities. Like the forest, the population of the Kresy was also diverse, not as in some countries where foreigners were relegated by language and poverty to the margins of society until a generation grew up assimilated. Diversity in the Kresy was organic, as natural to the landscape as were the flora and fauna of the forest. These communities were nations within a state, each with its own language, religion and customs, timeless like the forest and marsh in which new generations were born, matured, grew old and died in an endless cycle of regeneration. Like the forest, the nations were battered by wars, greed and wanton cruelty. In the last onslaught not only was life destroyed but the potential for regeneration was threatened.

Since the word “kresy” means “borderlands,” presumably the word ought to apply to any borderlands — north, south, east or west — but when Poles say they are from the Kresy, they mean the eastern borderlands. It is a word that evokes memories of a land of almost mythical beauty but also memories of exile and longing; it evokes feelings of loss and feelings of timelessness. Yet the first references to this area as “kresy” appeared only in the mid-nineteenth century, and the use of “Kresy” with the upper case “K” first appears only in post-war literature. Polish exiles in Siberia, displaced by the Soviet annexation of these lands during World War II, and the exiles who had escaped from Russia and were subsequently scattered across the globe, made “The Kresy” a synonym for the land of their birth, their country.

St. Jura Orthodox Church in Drohobycz

Source: Archives of New Records, Akta Jana i Ignacego Mizikowskich, album nr 3

The diversity of the Kresy, like diversity everywhere, inspired artistic and literary creativity. Here is the birthplace of Poland’s greatest poets, from Adam Mickiewicz whose 19th century work includes the “national poem,” Pan Tadeusz, to Nobel Prize-winner Czesław Miłosz, who was formed here by his multi-cultural roots. Pan Tadeusz begins with the words, “Lithuania, my fatherland…” This may strike outsiders as odd — a Polish national poem beginning with a salutation to “Lithuania, my fatherland” — but that is because they are accustomed to simple identities. Poles know that these borderlands were the historic lands of the ancient Lithuanian kingdom that stretched from the Baltic to Kiev and included what is now Belarus, Ukraine, eastern Poland and the small modern state of Lithuania. When the Lithuanian Kingdom united with the Kingdom of Poland, this new Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth stretched from the Baltic to the Black Sea, and from Kiev to the Oder. This new state had an official duality, akin perhaps to the official duality one finds in Canada – and an affinity for multiculturalism that seems to be more of a problem for states that are officially mono-ethnic in character. Recently, modern Lithuanians have claimed Mickiewicz as a Lithuanian poet. And why not? He is great enough to be shared. More important, as a man of the Kresy, he ought not be defined too narrowly since it was not unusual for the people there to say of themselves: “I am a citizen of the Polish state, belonging to such-and-such a nation and of such-and-such faith.” That the Commonwealth came to be known as the “Polish” state was largely due to the fact that the ruling classes of the different areas of the Kresy adopted the Polish language and customs, though not without their own distinctive flair, for better or for worse. In any case, classical Poland was a multi-ethnic state where for centuries lived a wide variety of people, professing a variety of religions and speaking more than one language.

Wooden Tatar mosque, Novogrodek, 1931

Source: Szypowski family private collection / Kresy-Siberia Foundation

Though the Poles dominated the state, in the Kresy they were not necessarily the majority, or even a plurality, in some of the towns or regions. Lithuanians, Jews, Ruthenians (Ukrainians) and Byelorussians predominated in some areas and smaller minorities — Armenians, Tatars, Gypsies, Karaites, Germans, Czechs, Greeks, Scots, and a sprinkling of Russians (primarily Old Believers), — added to the colour and flavour of many towns and cities.

Wilno, now Vilnius, in Lithuania, was the home of Poland’s second university. The first Polish university, the second in all of Europe, was established in Kraków in the 13th century and bears the name of the first king of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Jagiello, who was Lithuanian. The other king in this union of two monarchs and two crowns was Polish, Jadwiga, and they ruled as co-kings, equal in rank. Not much point in telling Polish women to be subservient; history tells them otherwise. The population in Wilno was primarily Polish and Jewish, with a very small number of Lithuanians, less than one percent on the eve of World War II.

Lwow, now L’viv, in the Ukraine, was a cosmopolitan city of many nationalities predominantly Poles and Jews but also Germans and Ukrainians, and was an important cultural centre for Armenians as well as home to other, smaller minorities. Zamośc, a 16th century Renaissance city built by Count Zamoyski and designed by the Italian architect, Bernardo Morando, was intended to be an “ideal town,” perhaps the only custom-built town in Europe. Conceived and completed within 25 years, the town was to recognize both the aesthetic and functional aspects of life, assuring the economic, intellectual, cultural and religious elements that are the basis of civilization. Its design included three markets, the Great Market serving as a forum publicum, a church, an academy, a town hall, and public, commercial and private construction all designed to enhance The Ideal. Even the population was planned, beginning with Count Zamoyski’s fellow Polish Catholics and quickly followed, by invitation, a group of Armenians, Sephardic Jews and Greeks. The magnificent Armenian houses with their intricately carved stone window frames still stand in the town square bearing witness to the wealth and style of these merchants.

Orthodox Church in Brest-Litovsk

Source: National Library

The houses of worship of the Kresy also reflected this diversity: Roman Catholic cathedrals and country churches, abbeys and convents; Orthodox and Uniate churches ranging from magnificent cathedrals to small chapels on isolated hills, all with their characteristic onion domes; magnificent Armenian churches; great stone synagogues in the cities and smaller wooden ones in the countryside; and the mosques of the Tatars, some resembling typical Polish wooden churches with graveyards around them nestled in a woodland glade.

In the middle of the 20th century, the people of the Kresy, along with the rest of Poland, suffered a tragedy unlike anywhere else in Europe: the simultaneous attack by the two most vicious totalitarian regimes in history, Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia. The Kresy was the epicentre of the battle between these two giants, wreaking unprecedented destruction on the people, the land, and yes, the great forest. The savagery of the onslaught was driven by ideologies dedicated to the eradication of all cultures in these lands to be replaced by their own. In the end, they failed, but not before committing crimes of unparalleled magnitude and irreversibly altering the ethnic composition of the population. The Polish Jewish nation was all but destroyed, millions of Poles, Ukrainians and Byelorussians were killed, millions more deported. The material losses were staggering, the cultural losses heartbreaking.

Narew. Postcard ca. 1916

Courtesy Kresy-Siberia virtual Museum. Tomasz Wisniewski collection.

Today, the children and grandchildren of the worldwide Kresy diaspora look for traces of the towns, villages and shtetls, the meandering rivers and rolling meadows, that they vaguely remember hearing about.

CR

For a superb history of the Białowieża forest, see The Białowieża Forest Saga by Simona Kossak, published by MUZA, SA , Warsaw.