Lost Between Worlds

Lost Between Worlds

By Edward H. Hertzbaum

Translated by Piotr Graff, edited by Krystyna J. Mew Matador

Leicester, UK

ISBN 978-1848766-037

Lost Between Worlds begins with a single paragraph, centred on a page, without attribution. The reader quickly discerns it is a short introduction to the book written by the author himself. If you were to pick this book up hesitantly, perhaps because as a reader you are war-weary, tragedy fatigued, atrocity exhausted, this modest yet exquisitely graceful paragraph attracts you despite your misgivings. Once you begin, you won’t stop.

The book is about the Second World War, its horror, its futility. The author, Edward Herzbaum, is a young man, relating events as they happen. They are terrifying events, a descent into hell, into war, and into the dystopia that was the Soviet Union, described with spare, unembellished prose.

He begins recording his story after normal life in Poland has already come to an end. In his opening sentence he states that he neither can, nor wants to, think about his life before the war.

Like a travel writer, he sticks to the time and place of the moment, to the people he encounters along the way. Early on, in a crowded and filthy prison, an elderly fellow prisoner introduces himself. “My name is Grapski.” They shake hands and Herzbaum replies, “It’s a pleasure…” The irony was not lost on him.

Transported to a country seemingly disconnected from its human element, with laws and rules devised by automatons blind to the sentient beings affected by them. Work quotas and food rations imposed by distant functionaries and indifferent to human capacities or needs. Although in this environment, the author is not of it. Coming unexpectedly upon a young woman, he tries not to frighten her. “The fate of a woman in a Russian camp is more terrible,” he writes, “a thousand times worse than the fate of the worst prostitutes.”

He wonders how landscapes of breathtaking beauty can be turned into vast slave colonies of skeletal men and women, ragged, filthy, covered in sores, their “commanders” virtual dictators, their guards almost always psychopathic criminals.

“You will get used to it or you will die,” they say. But Herzbaum does not get used to it. What keeps him going is anger, a cold fury. “I cannot surrender to those pigs. I will not die among those thugs…”

Occasionally he encounters Russians who, although not unkind, accept conditions unquestioningly. He likes them, but sees that they are from an alien world, a country of “modernized misery and organized famine.” He tells of a poignant exchange with a nurse who said that, “one day everything will be different; even flowers used to have lively colours, but now they have faded because they are afraid of the NKVD.”

Somehow, war news reaches the prisoners. They hear about Germany’s air attack on Britain and Britain’s victory; there are rumours that a German-Soviet war is imminent. The Germans attack, the Soviets need new allies.

Eventually, news of the Polish-Soviet agreement on prisoners reaches them. General Anders is released from the notorious Lubianka Prison in Moscow. Eagerly the freed Poles stream south, in search of their army.

The last entry on the last day of his captivity he notes golden rays of sun shining victorious in a clear blue sky. “Only now has it hit me how horrendous this nightmare behind barbed wire has been for us. How wildly happy I would be to go to the front, to die there, but not here.”

He is not a natural soldier – if anyone is; for one thing, his eyesight is poor. But he and his fellow Polish prisoners are free. There is not enough food, or equipment, tensions build up. There are occasional fights, but they are comrades, and in a half hour they are all “mates” again.

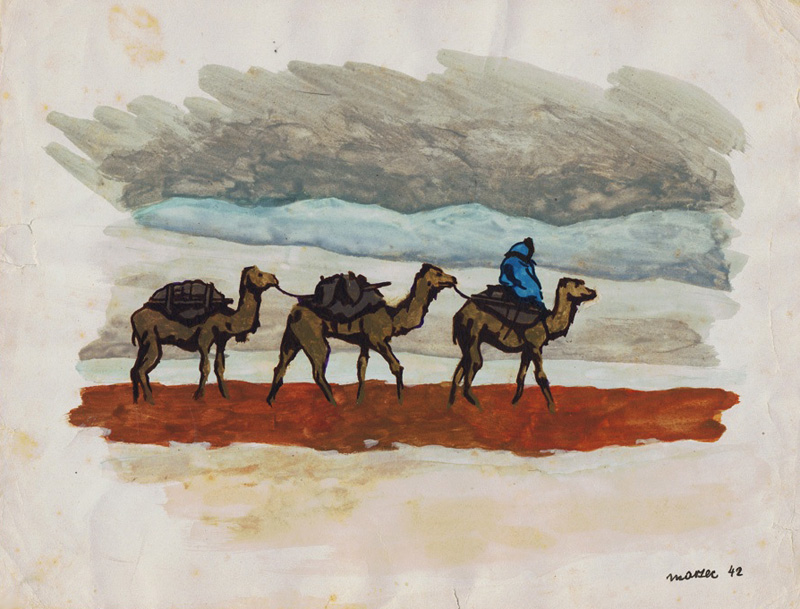

The army provides him with freedom, friendship, food, medical care… and notebooks. He continues his journal. As the army moves from Russia to the Middle East, the landscape is dazzling, ever changing. Herzbaum acquires watercolours and art paper. He is talented, his paintings complement his writing.

The news from Europe is disquieting. The soldiers have to regain their strength, get training. They are in Egypt, in Palestine, but they are restless. They have to fight the Germans. Herzbaum hears that his mother, who had remained in Łódź, died in 1940. [In fact she died in the Łódź Ghetto in 1942, in a typhus epidemic.]

Eventually the orders come; they are to join the British in Italy. At this point, Lost Between Worlds is at its most powerful. These are soldiers who know exactly what they are fighting for, exactly what they have lost, what the war had done to their homes, to their families. But they already know that for them there will be no victory.

Herzbaum’s description of the war in Italy is war literature at its best.

Early on, he writes: “If I’m afraid of something, it’s not death, but life. I am afraid of the first day after the war. This is frequent among us whom the war has deprived of everything and broken everything that we used to believe in.”

As time goes by, he notes the tedium of war, when “the front is very quiet; all we can hear is the grumbling of artillery at various distances.” Guard duty, on patrol, attending to provisions, repairing cables, sporadic shelling – and everyone moves as though this were normal.

Then a sudden artillery attack, shells bursting everywhere, an ammunition depot explodes, the whole valley on fire. “It’s a romantic picture of a battlefield. Orange fires, a burning cannon, a lot of scattered timber, shells and boxes… bomb craters, burnt out tanks and pieces of artillery with barrels twisted like pasta.” To this, “you add the people, or what remains of them.”

After Cassino, he reflects on the cemeteries he has seen – in the forests of Siberia with tiny, half broken, wooden crosses. Dzalalabad in hot, fiery clay; the desert mound in Khanaquin, crosses made of sheet metal or concrete.

But here, after Cassino, he is with a friend, and they wonder how many graves belong to people they knew, with whom they were talking just recently. A few mates from officers’ school, little Palukejski who had trained in snow wearing summer shoes; Stasek Iwanowicz, a keen footballer; the quiet Lucek Czerkowski who made them feel we could conquer the world. “… with each new name, it is as if a cold hand has been laid on the chest.”

“Why? Why were they lying here? None of them were prone to theatrical gestures, lofty words. They were just going about their business. It’s easy to say that they were paying for the glory or that they fell to create a legend. But they didn’t care about the legend… the grim legend of Cassino.”

Herzbaum suffers from depression. Alcohol brings neither pleasure nor relief. He wants to be with normal people, not soldiers; among friends, “like it used to be.” Tries to learn how to laugh but can’t. And discovers he can’t really drink either. But one addiction does help: the exhilaration of driving at full speed.

Towards the end of the book are some letters written to a cousin, obviously never mailed. About religion, he writes: “I don’t believe. And I’ve never had any problems with it… You think religion has done so much wrong? What about the ‘religion’ of the German Supermen? Or the ‘religion’ (it is one!) of Marx – Lenin – Stalin?

January 1945, Herzbaum speculates about the possibility of writing for a publication. A discreet inquiry because it is “against the rules.” And in the end, he packed his journals away in a box and never again mentioned the years 1939-1945. As did other Polish soldiers who knew that their story was not a comfortable truth.

You have to look in the back of the book, to the epilogue written by the author’s daughter, Krystyna Mew, to learn something about the author. Edward Herzbaum was born in 1920 in Vienna, the son of secular Polish Jews who moved back to Poland in 1930. After completing his high school education in Łódź in 1938, young Edward went on to study architecture at the Warsaw Polytechnic. He was a good student, culturally refined, confident about a successful career in his chosen field, architecture. He died in England in 1967 at the age of 46, a successful architect. It was not until decades later, when his wife died, that Ms. Mew discovered a trunk containing old, yellowed notebooks, some with scraps of paper glued into them.

It was a revelation, and yet, in a way, not a surprise. Growing up, she knew that she wasn’t “English,” like her friends, but was never able to find all the pieces to the puzzle. Her mother, a Polish Catholic, had lived through the German occupation, took part in the Warsaw uprising. But she, too, was silent about the past. Mew had a half sister who also lived with a mystery: never able to find out what happened to her father during the war.

Lost Between Worlds was published by Krystyna Mew, after she had tried unsuccessfully to find a publisher. This is a pity, because an introduction by a historian would be very valuable for readers not well versed in this aspect of World War II history. Perhaps this may still happen, for the book deserves serious attention. That said, Lost Between Worlds, handsomely illustrated with family photographs and Edward Herzbaum’s paintings, is a worthy addition to the literature.

CR

More information about Edward Herzbaum and further background on the book is available on www.lostbetweenworlds-herzbaum.com

Pingback: Kaia, Heroine of the 1944 Warsaw Rising

Pingback: February 1940: Exile, Odyssey, Redemption